State environmental regulators have abandoned plans to craft nitrate standards in areas that are vulnerable to groundwater contamination, saying the rulemaking process set by state lawmakers stands in the way.

In an email released by environmental groups last week, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources said that the Legislature’s rulemaking process and timelines “do not allow adequate time for the department to complete this proposed rule.”

The agency first proposed restrictions on manure spreading in areas with soils sensitive to groundwater pollution in December 2019. The DNR had 30 months to draft a rule and send it to the Legislature for approval.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Environmental groups say a 2017 law known as the REINS Act played a role in the rule’s demise, including Midwest Environmental Advocates, or MEA.

“I think that any significant public health protection promulgated by the DNR or other state agencies will run into problems with the REINS Act,” said Tony Wilkin Gibart, MEA’s executive director.

What is the REINS Act?

The Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act, or REINS Act, was signed into law by former Republican Gov. Scott Walker in 2017. Republican lawmakers have said it provides more scrutiny of agency regulations that could cost millions for businesses and taxpayers.

The law requires legislative approval of agency regulations that are expected to cost more than $10 million over any two-year period. It also requires a preliminary public hearing earlier in the approval process and allows an independent analysis of costs related to implementing agency rules.

Why did lawmakers pass the REINS Act?

At the time, state Sen. Devin LeMahieu, R-Oostburg, now the Senate Majority Leader, cited a 2010 DNR rule that curbs phosphorus runoff. The regulation set strict standards to limit phosphorus that’s released into the environment by wastewater treatment plants and industrial facilities.

Too much phosphorus can harm water quality and cause algae blooms, which can produce toxins that make people and animals sick.

A 2015 economic impact analysis estimated the phosphorus rule would cost businesses and communities $708 million each year. A 2012 DNR analysis estimated the state would see a net benefit of $18.8 million over 20 years through higher property values, increased recreation and avoided costs to clean up polluted waters.

How does the REINS Act affect the proposed rule?

Under the law, an agency proposing a rule must stop work on the regulation if its economic impact analysis indicates that $10 million or more would be spent or passed along to businesses, local governments or others over any two-year period to comply.

The DNR initially estimated the rule would cost farmers and small businesses less than $5 million per year to comply, but farm groups argued the standards could cost growers and producers billions of dollars each year.

“Most people, I think, agree that the rule actually costs enough that it would require some additional oversight by the Legislature, in which case, (it) probably faces an uphill battle to even make it past that initial hurdle,” said John Holevoet, government affairs director for the Wisconsin Dairy Business Association.

In September, a report commissioned by the DNR and prepared by University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers found the economic impact of the proposed standards would add up to between $22.5 million and $31 million annually.

What happens now that the DNR has dropped the rule?

A DNR spokesperson didn’t return a request for comment on the department’s decision to halt work. The agency said in its email announcing the move that it will continue to work on science and land management practices to address nitrate contamination.

Under the REINS Act, a proposed rule that exceeds the law’s cost threshold can’t move forward unless a lawmaker introduces a bill authorizing the agency to do so, and work may resume once the legislation passes. An agency could change the proposed regulation to ensure compliance costs don’t meet or exceed $10 million over any two-year period.

Environmental groups say the law is problematic because it focuses on the costs to polluters and doesn’t consider the economic benefits to families through avoided health care costs.

“Instead of working to ensure Wisconsinites have safe water, the Legislature created a system of barriers to developing public health protections, undermining the DNR and preventing the agency from reducing water pollution,” Clean Wisconsin said in a statement.

A report published last year found nitrate pollution in drinking water is linked to negative health outcomes that are costing people in Wisconsin between $23 million and $80 million each year in medical expenses.

Communities have spent an estimated $40 million to address nitrate pollution in public water supplies, and it could cost more than 10 times that amount to replace private wells that are contaminated.

LeMahieu and Republican state Rep. Adam Neylon, who co-chairs the Legislature’s joint rules committee, say the REINS Act is functioning as intended. Neylon said in an email that the DNR likely understood compliance costs of the rule to farmers and businesses would far exceed the law’s $10 million threshold.

“The rules process is designed to have checks and balances along with a strong public input component,” said LeMahieu in a statement. “If the DNR does not wish to pursue this open process, that is their choice.”

Nitrate contamination is a widespread problem

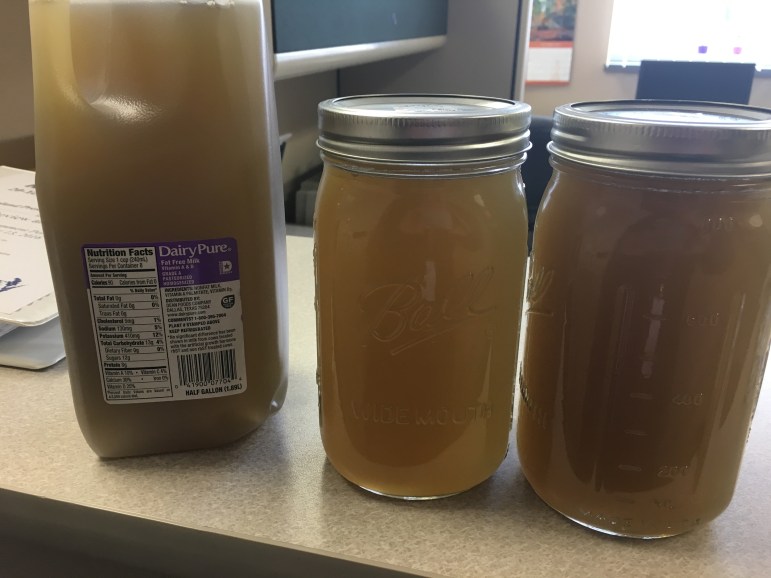

Nitrates are the state’s most widespread contaminant and have been associated with birth defects, thyroid disease and colon cancer. Research has shown around 10 percent of the state’s 800,000 private wells that provide drinking water to a quarter of the state’s residents exceed federal health standards for nitrates.

Around 90 percent of nitrogen in groundwater can be traced back to agriculture.

The Dairy Business Association and Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation say efforts are ongoing to address nitrate contamination. They pointed to a bipartisan group of lawmakers that recently introduced bills to help people address nitrate-contaminated wells and aid farmers with optimizing the use of nitrogen fertilizer on their land.

Karen Gefvert, the farm bureau’s innovation strategist, said on-farm research is needed to develop best practices for protecting groundwater, saying no two farms are alike.

“We need to give farmers the options of what those practices are and let them determine what’s best for their farms,” said Gefvert.

Holevoet suggested the Legislature could revive proposals to address groundwater pollution from manure runoff and contaminated wells that were among more than a dozen bills released by a water quality task force in 2019. Many of the bills passed the Assembly with bipartisan support, but they died in the Senate with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic last year.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.