Elizabethkingia continues to challenge epidemiologists as it afflicts people scattered throughout southern and eastern Wisconsin. It’s a type of gram-negative bacteria found commonly in the environment, but only rarely causes disease in humans. When an Elizabethkingia infection does strike, it’s dangerous because it tends to affect people with weakened immune systems. Moreover, these bacteria are often resistant to antibiotics. Since November 2015, the species, Elizabethkingia anophelis, has caused blood infections in 48 people in Wisconsin, 15 of whom have died.

As tracked by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, cases of Elizabethkingia have been reported in Columbia, Dane, Dodge, Fond du Lac, Jefferson, Milwaukee, Ozaukee, Racine, Sauk, Sheboygan, Washington and Waukesha counties. Most of the victims have been older than 65, and all were dealing with a serious illness of some kind at the time.

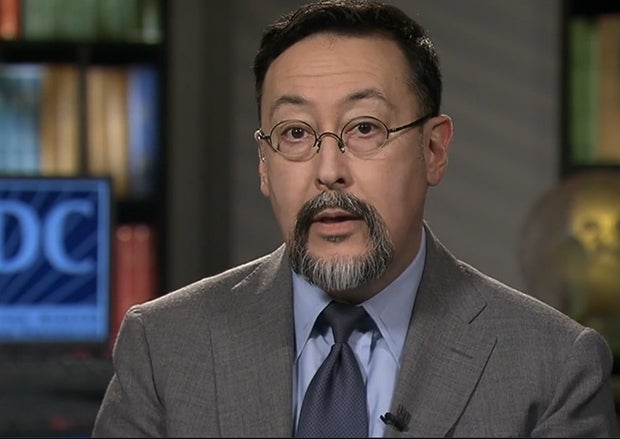

In a March 11, 2016 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s “Here And Now,” Michael Bell, deputy director for the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, shared what federal health officials know about the outbreak so far. He also explained why epidemiologists are having trouble determining its source.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Over a typical year, health officials generally report a half dozen or more Elizabethkingia infections in each state, Bell told host Frederica Freyberg, so it’s unusual to see so many cases concentrated in one geographic area within a few months.

“We don’t see 48 of the identical organism causing an outbreak like this very often,” he said. “In fact, this is probably the largest one we’ve seen.”

Bell explained that it can take about two weeks in the lab to determine whether or not a sample is contaminated with a specific bacteria. CDC and state officials have examined potential sources — including drinking water, medical products, healthcare facilities, and patients’ homes — but have yet to find a smoking gun. The best lead so far is that all of the Elizabethkingia anophelis specimens identified so far turned out to have the same genetic “fingerprint,” or marker of variation within its species — akin to genetic similarities among people born from the same mother.

“The fact that they all have one fingerprint makes us think that it could be one isolated source,” Bell said.

Bell also pointed out the upsides: Elizabethkingia is not contagious, people with healthy immune systems can easily avoid infection, and medical providers have identified some antibiotics that work against the strain found in Wisconsin.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.