There were plenty of nights when at the end of her 12-hour shift as a nurse in Madison, Ryann felt like she needed a glass of wine — or two — to wind down.

Whether it was the taxing hours, the increasing demands of charting or the traumatic medical scenes she watched unfold before her, the job and adrenaline that comes with it was hard to shake. That glass of wine after every shift became routine — one she knew wasn’t particularly healthy.

“I don’t know what light went off in my head, but part of it was like I realized that I was drinking every night that I got home. And for Wisconsin, it wasn’t a lot. It was like maybe two glasses of wine, but … I needed a drink when I got home and that’s not a good way to live your life,” said Ryann, whose last name isn’t being used to protect her privacy.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Ryann’s story isn’t unique. Nurses across the country report high levels of stress related to their jobs. A 2016 study on the impact of stress and the ability to cope among nurses found that 92 percent of those surveyed had moderate-to-very high levels of stress. Seventy-eight percent of nurses slept less than eight hours a night and 22 percent were classified as binge drinkers.

“There’s just so much that needs to get done … and you don’t really get to connect with patients as human beings at that point and that’s not why most people go into nursing,” Ryann said.

“When you have so many tasks that you just become this automaton … you don’t have time to educate your patients or really get to know them and understand why they’re having the problems they’re having,” she said. “It’s frustrating and it’s like a moral injury every day that you go to work.”

That sense of moral injury, along with repeated, on-the-job trauma can make nurses experience something called compassion fatigue — an indifference or inability to provide compassionate care due to the constant exposure to other people’s pain and suffering while feeling powerless to make a difference.

“Once you’re home … (I’ve) still got that adrenaline pumping in my body, I’m stressed out. You know, what do you do? Well, I’m going to have a glass of wine as soon as I step into my house, pour myself a glass of wine then like sit down and try to relax and kind of blow off some steam from the day,” Ryann said.

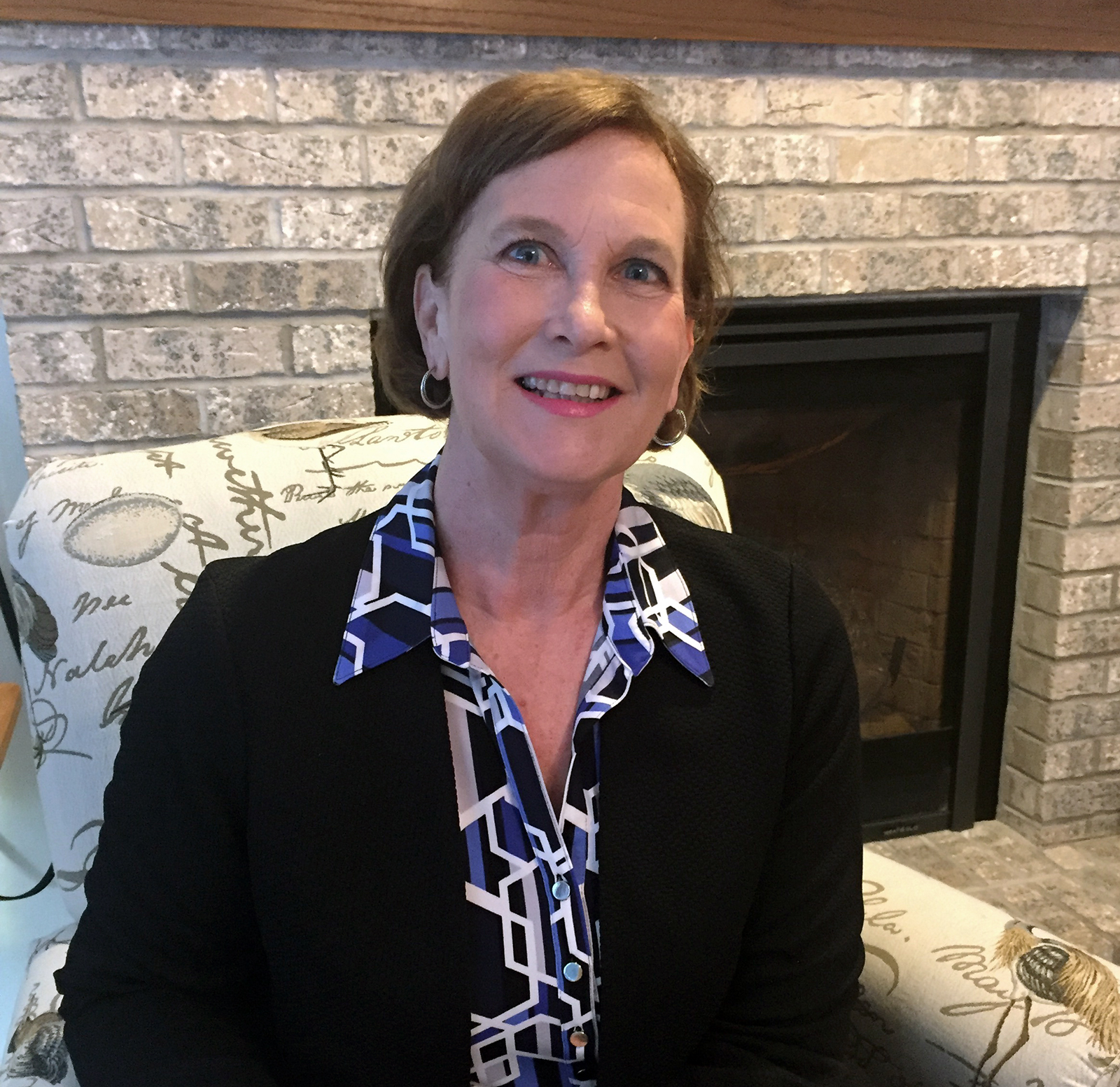

Gina Dennik-Champion is the CEO of the Wisconsin Nurses Association, a nonprofit lobbying group that represents Wisconsin’s 80,000 registered nurses. She said aside from workplace stress, nurses often don’t spend enough time taking care of themselves.

“We have our nursing code of ethics where we are responsible for our patients and for, you know, taking care of our profession, one another, as well as taking care of ourselves, and I think nurses sometimes really fall short on taking care of themselves because we take care of everybody else first,” Dennik-Champion said.

While workplace stress is well documented and hospitals across the country are promoting workplace wellness, a shortage of nurses and a culture that celebrates strength often means when nurses do need help, they don’t ask.

The ‘Supernurse’

Linsey Steege, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing, studies how to improve the health, safety and performance of health professionals. Her work points to what she calls the “supernurse” phenomenon.

“We’re nurses, we are like the postal service, we’re here no matter what for you at your time of need. And they are and that’s great, but it’s a double-edged sword.”

Associate Professor Linsey Steege

“That need and culture to be super creates a stigma around asking for help. It creates a stigma around showing signs of weakness and it creates, in some ways, some internal cultures within nursing that you’re not a real nurse if you haven’t worked 12 hours without peeing or taking a break, or if you haven’t worked five shifts in a row,” Steege said.

It’s a culture and mindset, Steege said, that many nurses have come to accept.

“We’re nurses, we are like the postal service, we’re here no matter what for you at your time of need. And they are and that’s great, but it’s a double-edged sword,” Steege said.

Beyond the stigma of seeming weak, there’s also a fear of the professional ramifications attached to asking for help with alcohol abuse disorders and problems with mental health.

“I think there’s so much stigma against it that people aren’t willing to talk about it with their coworkers unless they’re like really close friends because you are kind of worried about the repercussions if people start talking about that and then, let’s say, you make a med(ical) error or something and then you get sent like for a drug screening, I think there’s just too much stigma,” Ryann said.

Dennik-Champion wants nurses to feel safe and secure enough to admit to needing help, but she doesn’t deny it’s a scary position to be in.

“All health care providers have that fair amount of stress, I think it’s just that we don’t want to take the time to talk about it out loud or ‘I can talk about it but what am I going to do about it?’” she said. “It’s sort of that next step of ‘OK, I know I’m in trouble, what do I do?’ But that can be very scary, very scary for an individual.”

Nurses Caring For Nurses

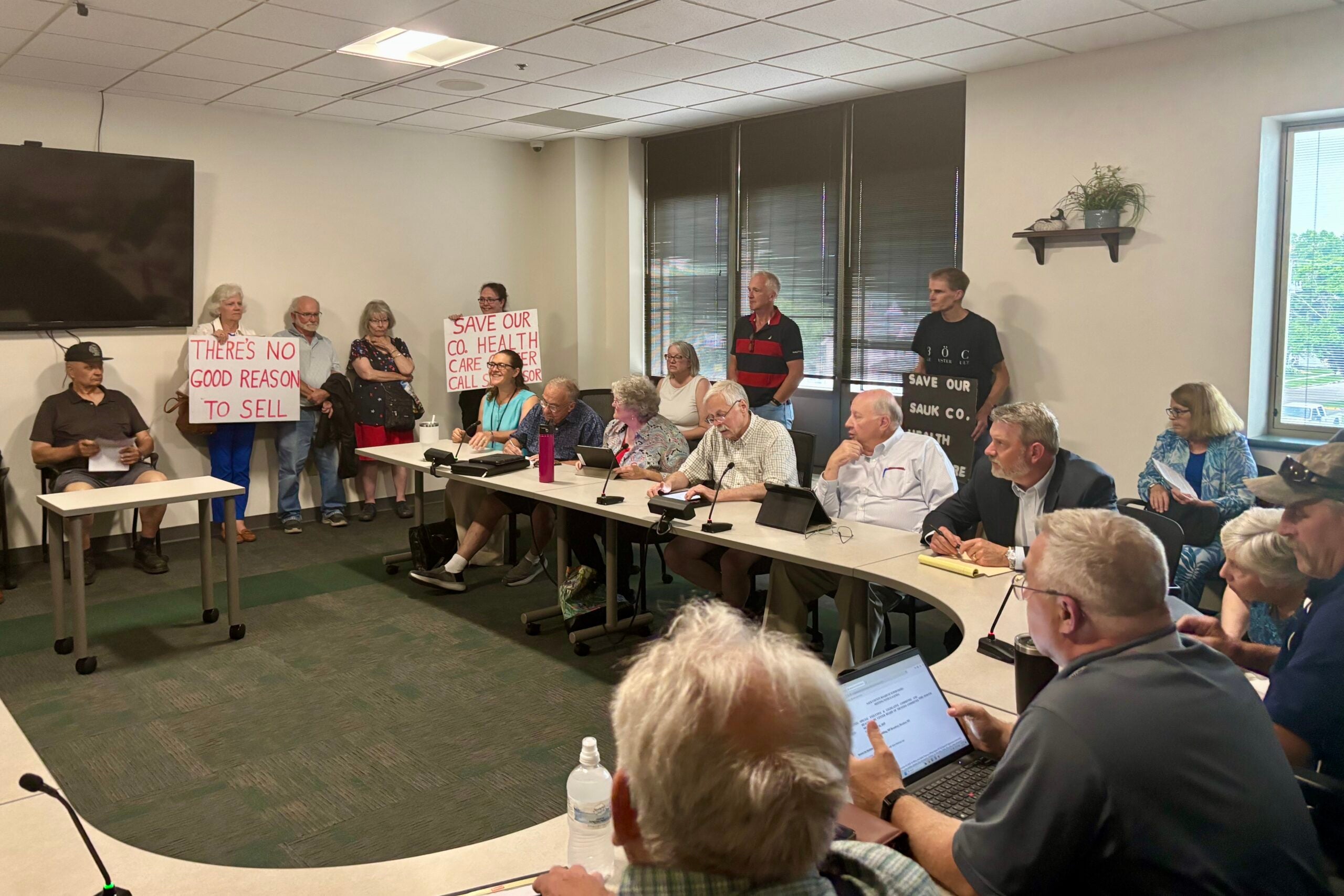

At one point, Wisconsin had a robust peer-to-peer support system for nurses dealing with substance abuse. Created and managed by the WNA, the Nurses Caring for Nurses program provided confidential support for nurses in recovery.

Dennik-Champion oversaw the program and said it has since fizzled out.

Most vibrant from about 2000 to 2010, the program had a team of volunteer nurses who served as mentors across the state. When a nurse needed assistance, they would call the WNA and get paired up with the closest mentor to strategize ways to navigate recovery and identify nearby resources.

“We were seeing nurses that were really trying to figure out how they can remain a nurse, remain a good person for their family and also remain a nurse that delivers safe care,” Dennik-Champion said.

But due to volunteer mentors retiring and moving away, the program lost its base within a five-year period. Attempts to revitalize it have been unsuccessful.

Dennik-Champion still wants to see the program come back, and with a new generation of nurses more aware of the dangers of stress and burnout — and a growing interest in talking about issues like substance abuse and mental illness — she’s hopeful.

“We know that the rate of alcohol abuse and the rate of opioid abuse is remaining the same … we know it’s not going away,” Dennik-Champion said. “What I’m hoping is that more nurses would be interested in helping be a mentor … (and) at the same time feeling that they’re really doing a very good thing for our patient population that needs us as well as the nursing profession who want to help take care of one another.”

A New Generation Of Nurses

Through her research, Steege has started to notice a shift among young and up-and-coming nurses.

“What we saw with some newer nurses and what we are sort of hoping — it’s not shown yet — is that maybe somewhat of a generational shift in terms of tolerance of that culture and wanting help and wanting to not self-sacrifice to a point of detriment,” she said.

After several years of working in a high-stress job, Ryann began to recognize that she was using alcohol to cope. While she doesn’t believe she ever would have qualified as having an alcohol abuse disorder, she knew the behavior was risky.

“I didn’t get drunk every night, I just had to have a glass of wine or two to relax, which I recognized is a slippery slope,” she said. “Alcoholism kind of runs in my family so it is something that I try to be conscious of.”

So Ryann made a change. She switched from working as a rotating nurse, filling in in whatever unit was the most short-staffed, to working in a slower-paced, more consistent unit. She also switched shifts.

“I switched to night shifts and that’s actually helped, like I don’t drink on days that I work at all now — partly like I’m not as stressed, I don’t feel the need for it, but also it just feels really weird to drink a glass of wine at eight in the morning,” she said.

While individuals continue to advocate for themselves and hospitals and clinics continue to implement wellness programs, others are looking to nursing schools to address the issues before they start.

Gina Bryan, a clinical professor and director of the Post-Graduate Psychiatric Certificate Program at UW-Madison, said “I can’t stress enough how this needs to start from day one for students.”

“We’re really trying to develop ways to systematically engage students — which is where we need to first start the conversation — in what does it mean to be well, what does it mean to be healthy, how do we do self-care? How do we communicate and get the support we need for what can be high levels of stress?” she said. “We don’t have some of that structure in place to teach yet and I think what we’re seeing nationally in health care professional schools — whether it be nursing, medicine, pharmacy — really start to look at wellness as providers. It’s been long overdue.”

Bryan added that any tools dedicated to increasing the well-being of nursing students often also end up benefiting their patients.

“The consequence of teaching health care providers healthy life skills, you know managing stress skills, mindfulness skills, is they then impart those skills to people we serve,” she said.

For Steege, taking care of nurses — reducing their stress and risk for developing substance abuse disorders — is the first step to improving patient care.

“We can’t talk about improving quality for patients without recognizing that this is a people-driven industry, the biggest technology or resource that we have is people,” Steege said. “We have to take care of them, they’re humans just like the rest of us.”