Often touted as one of the best ways to prevent lung cancer, quitting smoking by people who already have been diagnosed has been the ongoing goal of one initiative with ties to the UW Carbone Cancer Center in Madison.

The Cancer Center Cessation Initiative, which is funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Moonshot, began in 2017 and has been working to establish sustainable tobacco treatment programs throughout the United States for patients being treated at NCI cancer centers.

The UW Carbone Cancer Center — one of the program’s funded sites, and the only one in Wisconsin — has been implementing this initiative since it began. Its goal, says one of the center’s assistant scientists, Heather D’Angelo, is to address a gap in care.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“Quitting after your diagnosis can lead to much better outcomes,” she said. “But there’s not enough being done in our cancer care settings to actually connect people with the evidence-based treatment that they need.”

D’Angelo said 30 percent of cancers are caused by smoking.

Health care costs related to smoking accounts for an estimated 5 to 14 percent of the U.S.’s total health care expenditure. Having cancer and smoking at the same time is associated with death from all types of causes and developing other types of cancers. According to the American Cancer Society (ACS), smoking cigarettes increases risk for the following cancers: oral cavity and pharynx, larynx, lung, esophagus, pancreas, uterine cervix, kidney, bladder, stomach, colorectum, liver and myeloid leukemia.

The ACS states that 81 percent of lung cancer deaths in the U.S. are caused by smoking. Risk of getting lung cancer varies with how often and how many cigarettes are smoked. In 2018, more than 34 million American adults smoked.

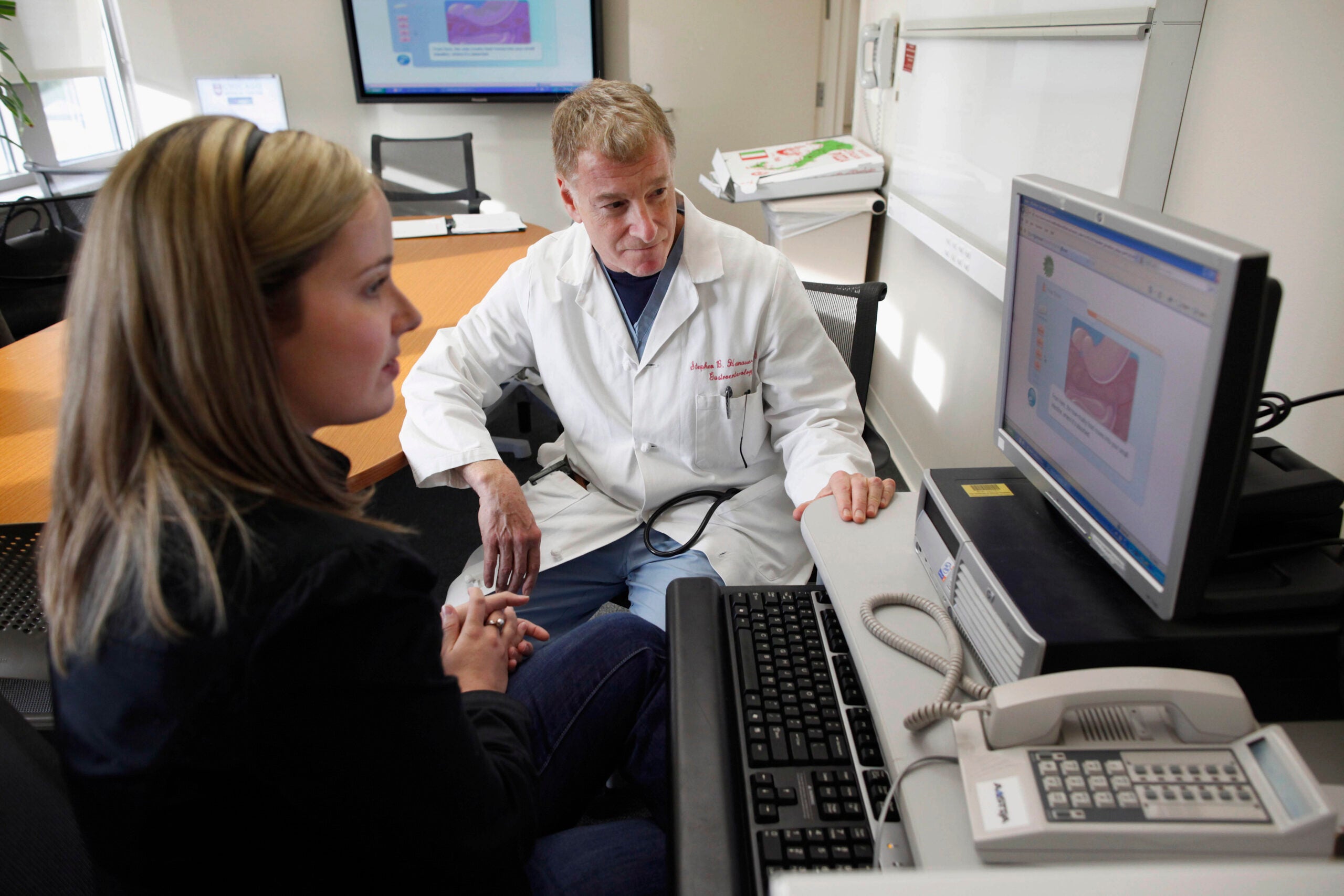

Staff at the cancer centers that are working with the cessation initiative will do three primary things: ask everyone who comes through the door if they use tobacco products; if they say yes, advise them to quit; and refer them to a smoking cessation treatment program.

D’Angelo’s work as part of the initiative is to assess those items to figure out what percentage of patients are being asked if they use tobacco and among those, what percentage is being reached by a treatment program. Then she’ll look at whether that person is still using tobacco six months after receiving treatment.

So far, data is showing that screening rates are higher than 95 percent at participating cancer centers, which number about 20 so far in the first cohort. Data is still trickling in when it comes to the percentage of smokers who are getting connected to treatment.

To be most effective, D’Angelo said smoking cessation programs should involve counseling and some kind of medication.

It’s important to connect smokers and other tobacco users specifically with tobacco treatment specialists or counselors who can work with cancer patients who are trying to quit. That’s especially because physicians and oncologists might not be trained or feel they have enough time to address quitting during primary visits with patients, D’Angelo said.

The funding for the second cohort of 22 cancer centers who are part of this initiative ends next year, D’Angelo said.

“We’re really hoping to continue the momentum of this initiative by keeping the researchers and clinicians who are working on these projects together,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.