Traci McMorran remembers speaking with her fiance Thomas Benser on Wednesday, Nov. 11 — Veterans Day.

“And then Thursday, I got an email from him saying, ‘This is going to be short,’ he said, ‘because I’m feeling very weak. I will try to call Saturday if I can,’” said McMorran.

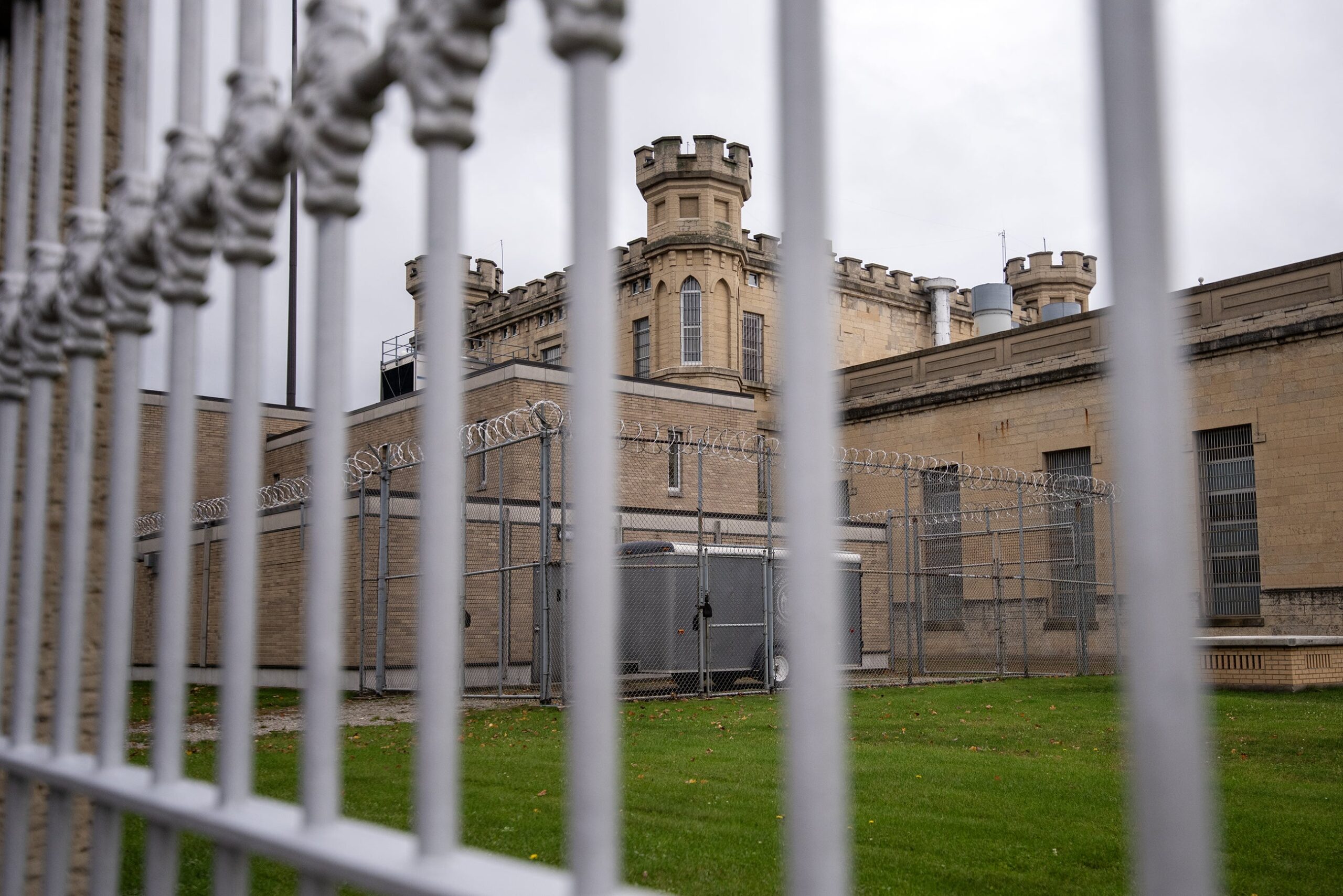

Benser is in the Oshkosh Correctional Institution for reckless endangerment after shooting at deputies in 2018. McMorran said at the time, Benser had severe alcohol problems and wanted to end his life.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

McMorran grew worried because her fiance has asthma and diabetes. In his email, he said he had put a request in to see a nurse.

“When I called on Saturday, the nurse said, ‘I can’t tell you anything.’ She said, ‘But, all I can say is if you’re religious, please pray.’ That’s what she told me,” said McMorran. “So right away, my mind went to the worst.”

McMorran called every day asking for information about Benser’s condition. But, without a signed release form, staff said they couldn’t share anything due to federal patient privacy regulations. After a week, she said they got verbal permission from him to share that he had been hospitalized after contracting COVID-19.

“I’m just glad to know … that he’s still alive because I didn’t know,” she said. “I didn’t know if (he) was dead or alive.”

As of Tuesday, Oshkosh Correctional Institution had the most confirmed cases of COVID-19 of any facility in the state prison system. State data show the majority of inmates infected have recovered.

Corrections officials say they’ve taken a number of steps to prevent the spread of the virus in facilities. Staff are required to wear masks and be screened before entering correctional institutions. Other measures have been taken to slow the spread by limiting movement of inmates or placing them under isolation and quarantine. Prisoners have been provided a minimum of three cloth masks that can be washed and reused. Officials say they’ve enhanced cleaning and sanitation.

Despite precautions, more than 1,700 corrections staff and more than one third of Wisconsin prisoners have now tested positive for coronavirus, and at least 11 inmates have died during the pandemic, according to figures from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections (DOC). Around 5,800 inmates are currently under isolation or quarantine. Health officials say correctional facilities face significant challenges in reducing the spread of the disease due to crowding, shared facilities and staff who come and go each day.

Last week, the DOC reported more than 800 cases on Nov. 16 that officials say is due to mass testing results that came in over the weekend. As the virus spreads, family members and loved ones of those behind bars feel they’re being left in the dark.

Family members say they may lose contact with inmates during lockdowns or when prisoners are too sick to call or email. Wisconsin Public Radio received several questions from family members through WHYsconsin about their concerns communicating with loved ones behind bars. WPR spoke to half a dozen family members and loved ones who fear they won’t be able to find out information about their loved one’s health status.

Policy On Notifying People When Inmates Are Hospitalized

The DOC has a policy for notifying family members when a prisoner is hospitalized. Corrections Secretary Kevin Carr said that occurs when patients are deemed incapacitated, near death or a warden believes it’s in the best interest of the inmate.

“If one or more of those criteria are met, we notify emergency contacts, the next of kin or legal guardian, etc.,” said Carr. “Now, that’s the case for any person in our care that is hospitalized for any reason, not just COVID-19.”

Carr said the policy is generally in place for security reasons. McMorran said she believes she’s listed as an emergency contact, but the rule is little comfort as she was left to wonder about her fiance’s condition for a week.

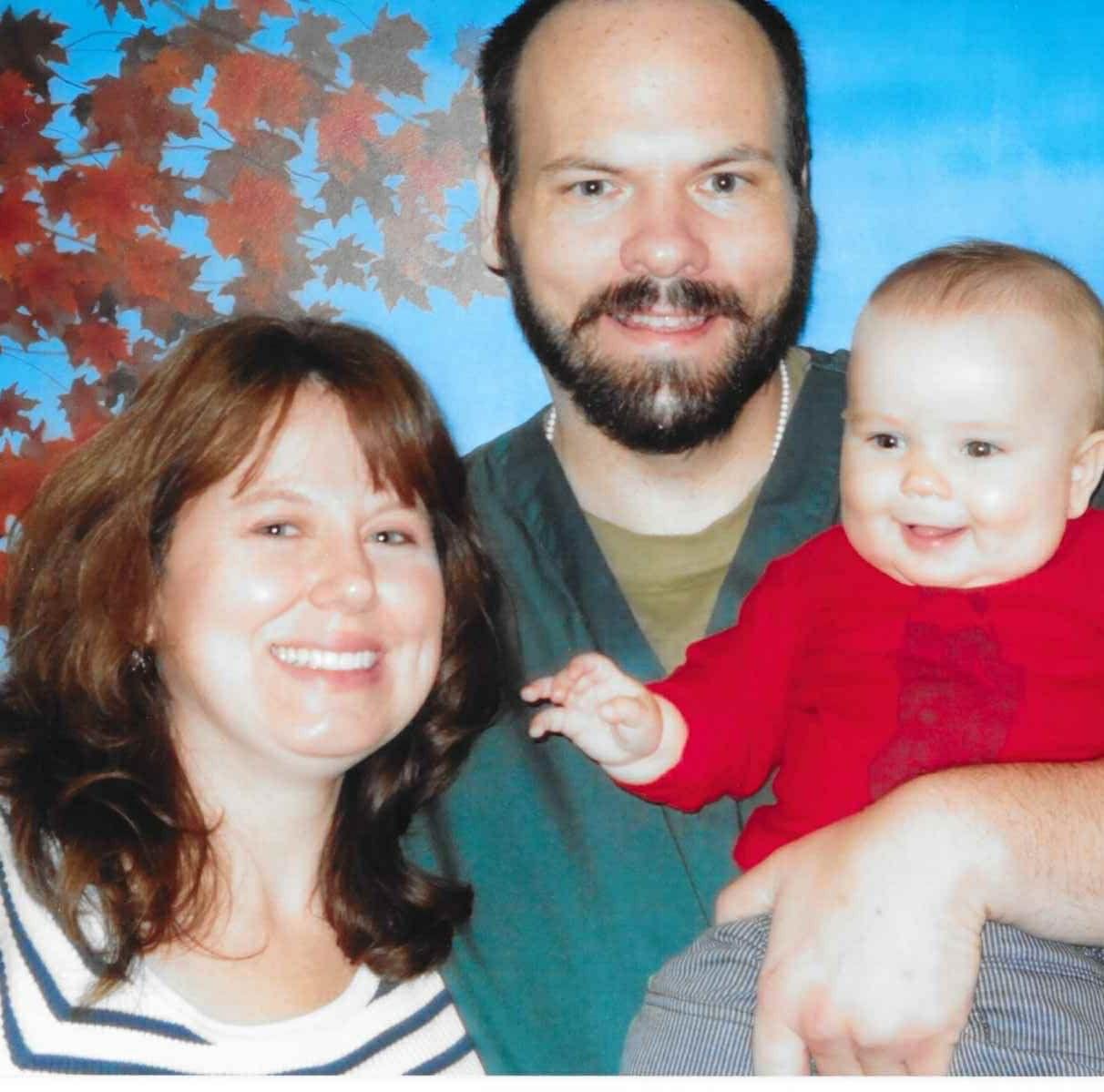

[[{“fid”:”1389106″,”view_mode”:”embed_portrait”,”fields”:{“alt”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”,”title”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″,”format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EShaunta%20Gibbs%20with%20her%20fiance%20Cornelius%20Wickliffe%20who%20is%20being%20held%20in%20the%20Milwaukee%20Secure%20Detention%20Facility.%3Cbr%20%2F%3E%0A%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Shaunta%20Gibbs%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“2”:{“alt”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”,”title”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″,”format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EShaunta%20Gibbs%20with%20her%20fiance%20Cornelius%20Wickliffe%20who%20is%20being%20held%20in%20the%20Milwaukee%20Secure%20Detention%20Facility.%3Cbr%20%2F%3E%0A%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Shaunta%20Gibbs%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”,”title”:”Shaunta Gibbs And Her Fiance Cornelius Wickliffe”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″}}]]Cornelius Wickliffe calls his fiancee Shaunta Gibbs every day from the Milwaukee Secure Detention Facility. He’s being held there on a probation violation after being convicted of drug possession. In a phone interview Friday, he said several floors were on lockdown due to COVID-19. Wickliffe is worried because he has diabetes.

“We had one inmate that was in my pod — I’m on the fifth floor — that ended up having it,” said Wickliffe. “So, basically, it’s like the inmates is the ones that’s in here spraying everything down and trying to keep everything clean to keep from getting (COVID-19).”

He said inmates are mostly confined to their cells and a week may go by before they’re allowed to shower.

Correction officials say showers may be limited as a social distancing measure when a facility has a high rate of positive cases. Milwaukee Secure Detention Facility has seen COVID-19 cases nearly double since Nov. 6 from 46 to 89 cases as of Monday.

“I just fear for my life,” said Wickliffe. “Like man, if I were to die in here, she would not know about it probably for a couple of days.”

Gibbs said that’s why he calls every day.

“He knows if a day goes by, and I haven’t heard from him, I’m going to freak out,” said Gibbs.

Wickliffe said he’s now being let out of his cell for 50 minutes each day — leaving less time for them to connect.

Gibbs said she hasn’t been listed as an emergency contact, and she hasn’t filled out any release forms.

The same is true for Madison resident Anna Wineland whose fiance Will Fleming is being held at Kettle Moraine Correctional Institution. Wineland said he was on probation for alcohol-related offenses, but Fleming was sent back to prison after he was convicted of burglary following a relapse.

Wineland said the increasing number of cases in the state’s prisons is frightening as she waits for him to call.

“I keep thinking, ‘Well, what if he does get sick? You know, is anyone gonna notify me? Or where will he be?’” said Wineland. “I just don’t have any control or any information.”

A DOC spokesperson said inmates fill out forms designating their emergency contact when they enter the prison system at the state’s intake facility.

State public defender Kelli Thompson said their attorneys have also had difficulty getting information from clients when individuals are quarantined. She said their offices are receiving hundreds, if not thousands, of calls from family members who are worried about their loved ones.

“They’re looking for that connection … and so that lack of communication, that’s so difficult for everyone,” said Thompson.

The DOC has received numerous calls asking officials to conduct a welfare check on a loved one behind bars. With roughly 20,000 people in the system, Carr said it’s difficult to keep up with every request.

“Because as COVID-19 positives have affected our communities, it’s also affecting the number of staff that we have available in our facilities to conduct that kind of activity,” said Carr.

Carr added the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, more commonly known as HIPAA, limits what medical information they can share without a person’s consent.

Federal Patient Privacy Law May Not Prevent Prisons From Releasing Details

The federal patient privacy law may not apply to Wisconsin prisons, said Elizabeth Gray, a health policy researcher and teaching assistant professor with George Washington University.

“Even if HIPAA were to apply, it’s not like HIPAA bars the disclosure of information in all cases,” said Gray.

Gray said the law is often misunderstood and officials typically err on the side of caution to avoid running afoul of the rules. In Wisconsin, corrections officials just recently began reporting data on how many prisoners had died from the disease after first citing privacy concerns.

Gray said corrections staff could cover their bases by asking inmates to fill out release forms ahead of time that would allow their medical information to be shared.

“I would think that, again, from that empathy perspective, just at least disclosing they’re alive or not, or they’re in a clinical facility … that would be something I would expect that they would at least want to share and they could share,” said Gray.

Martin Horn, a former top corrections official for Pennsylvania and New York City, said prisons could also increase inmate access to phones or set up an information line for families.

“The prison system would be well advised to do that,” said Horn. “The last thing you want is rumors running wild, so you want to have a way of conveying accurate information to families.”

Corrections Secretary Carr said he’s sensitive to the concerns of friends and family who have loved ones in the state’s prisons and their desire for information.

“We still are allowing phone calls and communication to occur by email and Zoom by folks who are in our custody who have tested positive,” said Carr. “We do everything that we can to still allow as much communication with families as possible.”

In McMorran’s case, corrections staff did seek out her fiance’s consent, so they could share information with her. McMorran spoke to Benser on Monday for the first time since he was hospitalized. She said he’s back at Oshkosh and doing well.

Still, she thinks the DOC and Gov. Tony Evers should be doing more to release prisoners who are vulnerable to the disease.

“I believe that there is a lot of people in there that could be released,” said McMorran.

Family Members, Groups Call For Release Of Prisoners

On Tuesday, prison reform advocacy groups gathered outside the governor’s mansion in Madison to call for reducing the prison population further to address the spread of COVID-19 in state prisons.

David Liners, state director of the faith-based reform group WISDOM, said Evers ran for governor on a platform to reduce the state’s prison population.

“The governor can’t keep pretending that this isn’t a problem, and he can’t keep complaining that the Republicans are ignoring COVID-19 when he’s ignoring it in a particularly vulnerable group of people that are under his responsibility,” said Liners.

A spokesperson for Evers didn’t return a request for comment. In October, Evers said the surge in cases across the state is also being felt within the state’s correctional facilities.

“Once we are able to make sure that people are safe and being cautious outside of the correctional institutions, we’ll see a decrease in the numbers that we see internally,” said Evers in an Oct. 15 public health briefing.

Throughout the pandemic, the DOC has taken steps to release inmates that include those who are doing alternatives to revocation sanctions at the Milwaukee Secure Detention Facility. The agency has also reduced the number of holds in county jails by more than a third, Carr said. He said a small number of prisoners are eligible to be released before serving their sentence.

“I can make a referral, for instance, for people who have an extraordinary health condition, and happened to be over 65. But, all I can do is make a referral to a court,” said Carr. “The court ultimately makes the decision whether or not to release somebody.”

Photo courtesy of Anna Wineland

During the pandemic, the state’s prison population has been reduced to its lowest level in nearly two decades as more than 2,500 people have been released due to the expansion of the Earned Release Program. The program is an early release treatment program for nonviolent offenders with substance abuse disorders. A DOC committee is recommending the program be expanded further by increasing inmates who are eligible.

The proposed changes would allow individuals at medium-security prisons to enroll and authorize enrollment within four years of an inmate’s release date instead of the current three-year requirement. Carr said they would remove a provision that prevents inmates from enrolling in the program again if they failed to successfully complete it the first time.

The agency estimates 1,000 more people would be able to complete the program if the proposed policy changes are adopted. For Wineland, that means her fiance could be eligible for release sooner. She said those behind bars shouldn’t be neglected or forgotten.

“They’re people’s fathers and husbands and sons, and they’re loved,” said Wineland. “They need to be taken care of as well, just like everybody else.”