On the day her first son was born, Lydi Dodge’s father died of a drug overdose.

Two years later, her mother died from liver failure stemming from a battle with alcoholism.

By the time she was just 21, both of her parents were dead. She started taking pain pills to help deal with the grief.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“He’s (Dad) the one who raised me, so that was a lot to take in,” Dodge said. “And that’s how I got started on the pills, because they were so available from the doctor at the time.”

Dodge started small, with prescription pills. But it didn’t take long for her drug use to take a sharp turn.

She quickly got hooked on meth, and then heroin. About five years ago, she began using fentanyl, an extremely powerful — and deadly — synthetic opioid.

“It just got really, really bad,” Dodge said. “There was no coming back.”

Dodge, now 29-years-old, is a direct descendant of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. She lived in the village of Keshena in the heart of the Menominee Indian Reservation for several years while she battled substance abuse.

It was a place she’d use and often sell drugs. She was not the only one.

Menominee County has the highest overdose death rate in all of Wisconsin, according to statewide overdose death data. In 2022, the tribe saw 16 overdose deaths — its highest number on record.

The Menominee Indian Tribe is not the only tribe dealing with this issue. Wisconsin Department of Health Services Director of Opioid Initiatives Paul Krupski said the 12 tribal nations across the state have the highest overdose rate of any population.

“When we look at data, our tribal nations are disproportionately impacted by the opioid crisis in our state,” Krupski said during a February press conference.

A 2022 report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also found national overdose death rates increased 39 percent for American Indians from 2019 to 2020. That trend isn’t slowing down, according to the CDC.

But with a renewed focus on the issue, Menominee tribal leaders are hoping to put an end to the deaths.

Today, Dodge, now nearly 20 months sober, is back on the reservation to provide input and feedback for the tribe’s recent efforts to reverse the trend.

“My heart is in changing the communities that I grew up in,” Dodge said. “That’s where I’m trying to help.”

Sudden surge in overdoses led to creation of new team

The Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin reservation is located in northeastern Wisconsin, about 45 miles northwest of Green Bay. In the early 1800s, the tribe occupied a land base of an estimated 10 million acres. But treaties with the federal government eroded that number to around 235,000 acres today.

The tribe has around 8,500 members today, some of whom work at the Menominee Casino Resort, located on the reservation. But less than half of the tribe’s members are able to live on the reservation because housing and jobs there are scarce, according to the tribe. According to the U.S. Census, about 24 percent of the county is estimated to be living in poverty.

In the heart of the reservation lies a newly constructed community resource center. On a sunny Monday in January, it played host to the Drug Intervention Team.

Three sudden overdose deaths at the start of 2022 led to an emergency meeting in March of that year and the creation of the team. Nearly a year later, representatives from tribal leadership, law enforcement and health services are still working to tackle the issue.

Tribal Chair Ronald Corn Sr. believes more than 50 percent of the population of the tribe is dealing with addiction. But he hopes the work of the team will help reverse the trends.

“We’re just trying to get our arms around a huge problem here on our reservation,” Corn said during the meeting.

The issue of drug overdoses was especially bad over the recent holiday season. Between Dec. 22 and Jan. 2, the Menominee Tribal Police Department responded to two or three overdoses per day, police said.

“We can go from one case to the next, to the next,” Menominee Police Chief Keith Tourtillott said. “We’ll respond to one situation, the person gets up and runs, and we’re chasing the person trying to get them so we can get them help, and then we get another call that we have to respond to.”

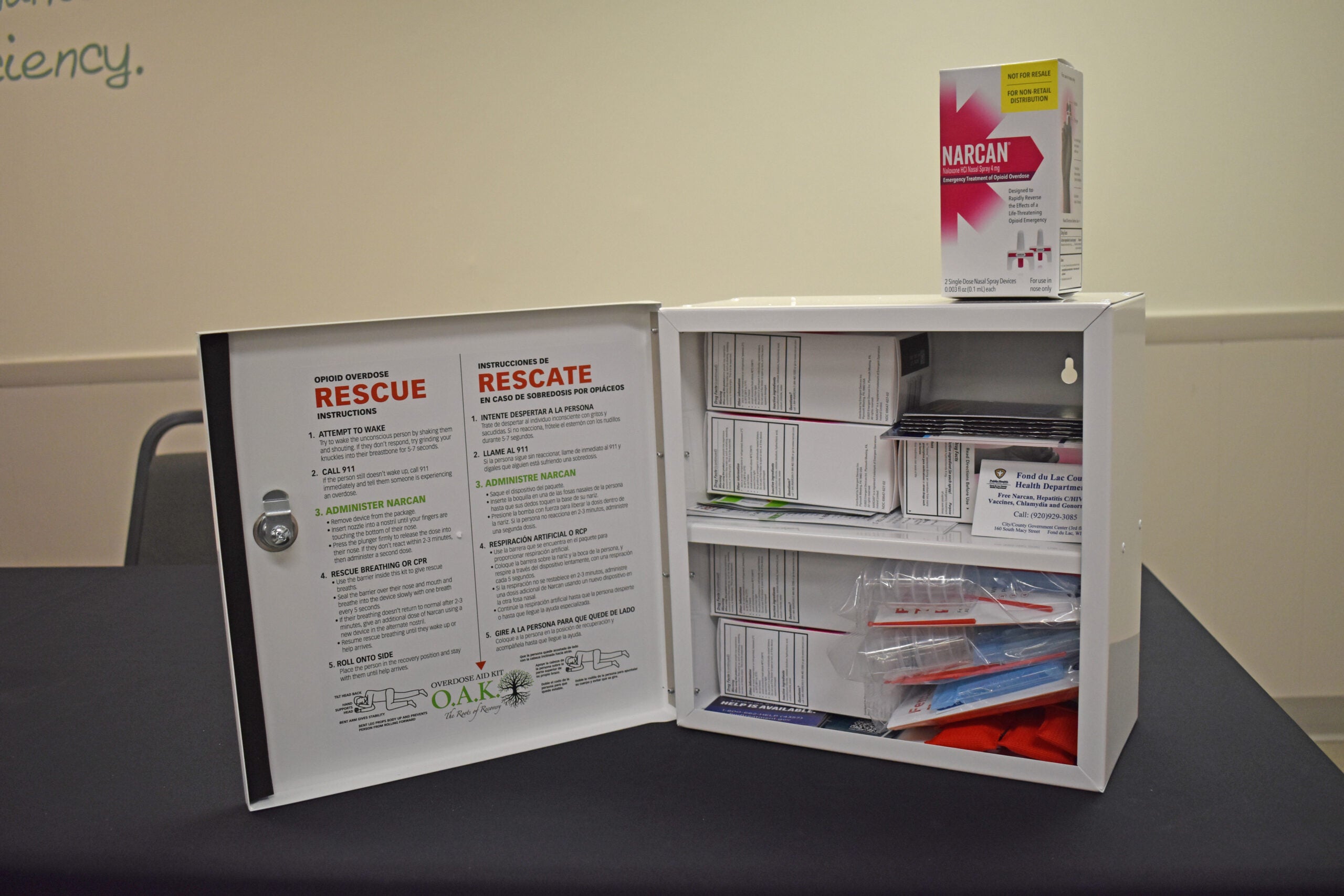

Tourtillott said many of the calls come in because individuals know they’ll receive Narcan, an overdose reversal medication.

“We make Narcan available so we can help combat the deaths,” Tourtillott said. “But we need to make sure that we can get to them and get them to treatment and get them help. That’s what this whole organization (drug intervention team) is about.”

The team has nine main goals, including tracking opioid use and overdose data, increasing communication about the issue and expanding behavioral health services and medication-assisted treatment programs.

Addie Caldwell, the director of Maehnowesekiyah Wellness Center, said the tribe started collecting more detailed information on drug overdoses in 2018. But it began seeing the issue rise in 2015 and 2016.

“It affects every single person on this reservation,” Caldwell said. “It doesn’t matter who you are. We all have someone within our families or ourselves who is struggling with this.”

Nationally, the first wave of the opioid epidemic was subsiding by the early 2010s. The second wave began shortly after, with rapid increases in overdose deaths involving heroin.

But overdose deaths caused by synthetic opioids, and especially fentanyl, have been increasing since 2013.The reservation isn’t immune to that trend. Fentanyl is 80 to 100 times stronger than morphine, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency. Just 2 milligrams of the drug is lethal to most people.

Tourtillott said they’re seeing fentanyl show up in “everything,” even in marijuana.

Caldwell said drug use is often normalized on the reservation and among many families and youths as well. She’s seeing and hearing about drug use in children in middle and high school, as well as among the elderly.

“We have multiple generations sometimes in one household, and if one person is struggling with addiction, that potentially is being seen by younger kids,” she said.

In recent years, the tribe has increased public awareness campaigns about the issue, including information about its medication-assisted treatment program. Dodge, who often attends team meetings, is encouraged the tribe is taking action.

“The leaders … understand there is a drug problem. It’s a drug epidemic in our communities, and something needs to be done to change it,” Dodge said.

Tribe is making progress

The tribe is seeking to coordinate with law enforcement and increase prevention and treatment efforts to combat the rise.

It receives the drug naloxone, marketed as Narcan, through the state’s Narcan Direct program. The state also supplies the tribe with fentanyl testing strips that can be used to identify the presence of fentanyl in unregulated drugs.

The Maehnowesekiyah Wellness Center and Menominee Tribal Clinic have started completing crisis assessments within 24 hours for those suffering from substance abuse problems. Fees for crisis assessments have also been removed.

The tribe also recently contracted with a public information firm to increase public awareness about the issue and what the team is doing.

Officials are looking to expand their medication-assisted treatment program through an agreement with Indigenous Pact, a tribal health care consulting company. Medication-assisted treatment centers prescribe medication for those suffering from addiction to help with withdrawal. That can be paired with counseling to help sustain recovery.

Caldwell said the tribe recently finalized a partnership to get more recovery coaches through Unity Recovery Services, an Appleton-based recovery support company. Those coaches will be available 24/7 through a hotline anyone can call for support or information on beginning to fight an addiction.

“Those recovery coaches will essentially walk with that individual through that process, so they feel support and they feel like someone is on their side and willing to work with them,” Caldwell said.

The tribe is also considering implementing an overdose fatality review. Dan Burns, a public safety specialist working with the tribe, recently attended an overdose fatality review in Milwaukee County, which is also experiencing record numbers of overdose deaths. That group looks for risk factors leading up to an overdose death.

“I think this kind of format would be so impactful because it (tribe) is such a close-knit community, and we can take away a lot of lessons and make a lot of impact,” Burns said.

Ben Warrington, the emergency management coordinator for the tribe, said after law enforcement gives someone Narcan, the tribe could do a better job at checking back with that person, to make sure they’re getting help.

“That’s where we’re struggling,” Warrington said. “There’s not a well-defined outreach process. That’s what we’re really trying to get these recovery coaches up and running for.”

Caldwell said individualizing treatment for people is an important part of the approach as well.

“We have to meet them where they’re at. We have to be able to individualize that treatment, because it does look different for a lot of people,” Caldwell said.

Tribes across Wisconsin also received $6 million in a multi-billion-dollar settlement with pharmaceutical companies that distributed addictive opioids to put toward prevention, harm reduction and recovery services. But those funds, the result of yearslong lawsuits by 46 states including Wisconsin, haven’t been distributed to individual tribes yet.

Rates higher among Native Americans

For Dodge, being involved on the committee is both a way of maintaining her own sobriety and a way of giving back to her community. As she grows older, she’s now motivated by her children.

Dodge’s addiction led to her losing custody of her five children. She was stuck in an abusive relationship. She had been in jail several times. She had lost relationships with her family and friends.

But after a stint in jail and drug court in 2021, Dodge decided to finally change her life for the better.

Before she went to jail, she remembers praying: “I’m sick of living like this. I want to get sober, I want to get clean.”

She believes that saved her life.

She now serves as a recovery coach in Shawano County for others who are still struggling with their drug use. She’s regained custody of her children, ages 10, 8, 6, 5 and 4, and said she is in a new, healthy relationship. She has had a sixth child, now 6 months old.

Dodge hopes her story is an encouragement to others suffering with their own addiction.

“Now that I’m sober, I’ll feel like I succeeded if my kids succeed,” she said. “I don’t ever want them to feel the feelings that I felt at such a young age. I don’t ever want them to be able to go through that.”

Dodge said she wasn’t taught about the negative effects of drugs or alcohol at a young age. She wants that to change, so she’s now talking to her children about the issue.

“When it comes to my kids — because I don’t want them feeling like I felt when I was a child — I’m open, I’m honest,” Dodge said. “It sucks, right, because kids shouldn’t have to know about that, but in this day and age, they do need to know about it.”

Overdose deaths were tapering off before the COVID-19 pandemic. But since the pandemic began, overdose deaths have hit record highs across the nation, including in Wisconsin.

There were 1,427 opioid-related deaths in the state in 2021. That’s a 16 percent increase over 2020 and a 70 percent increase over the number of deaths in 2018.

A Wisconsin Department of Health Services report found that the stress and isolation suffered by many during the coronavirus pandemic as possible reasons behind the large increase in drug overdoses and deaths in Wisconsin. Caldwell said the pandemic’s effect on people’s mental health was felt acutely on the reservation.

“When we normalize substance use, because we have so many people struggling, a lot of people turn to substance use when they’re struggling with mental health concerns,” Caldwell said.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the overdose death rate for American Indians nationally was also the highest for any ethnic group in the United States. A report from the CDC found death rates for American Indian and Alaska Native women ages 25 to 44 were nearly twice that of white women of the same age.

American Indians experience higher rates of substance abuse, compared to other racial and ethnic groups across the nation. The Red Road, a Native American advocacy group, indicated that the long history of oppression against American Indians and native populations is part of the reason why.

“This legacy of trauma, as well as the social isolation, poverty, education, high incarceration rates and inadequate access to health care on reservations are all root factors of substance abuse,” a report from the Red Road said.

A 2011 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said only about 12 percent of Native Americans receive treatment for substance abuse. American Addiction Centers said there are many possible reasons for that.

“These low rates of recovery program engagement may be in part due to significant barriers to treatment that native communities face, including transportation issues, lack of health insurance or poor insurance coverage, poverty, cultural stigma associated with substance abuse, and a shortage of appropriate rehabilitation and treatment options in regions where native populations are concentrated,” an American Addiction Centers report said.

But Caldwell believes with the help of the team, there’s a path forward to decrease the number of overdoses this year. She also said the path to recovery begins within individual families.

“It starts at home,” Caldwell said. “This starts with us recognizing that our families are hurting that we’re hurting, and realizing that we have to open that door to get help because if we don’t open that door and work on that healing, then it’s just allowing that cycle to continue.”

Do you need help?

If you or someone you know is struggling with addiction, call the Wisconsin Addiction Recovery Helpline at 211 or text your ZIP code to 898211.

You can also learn more about treatment options or how to respond to an overdose at: dhs.wisconsin.gov/opioids/index.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.