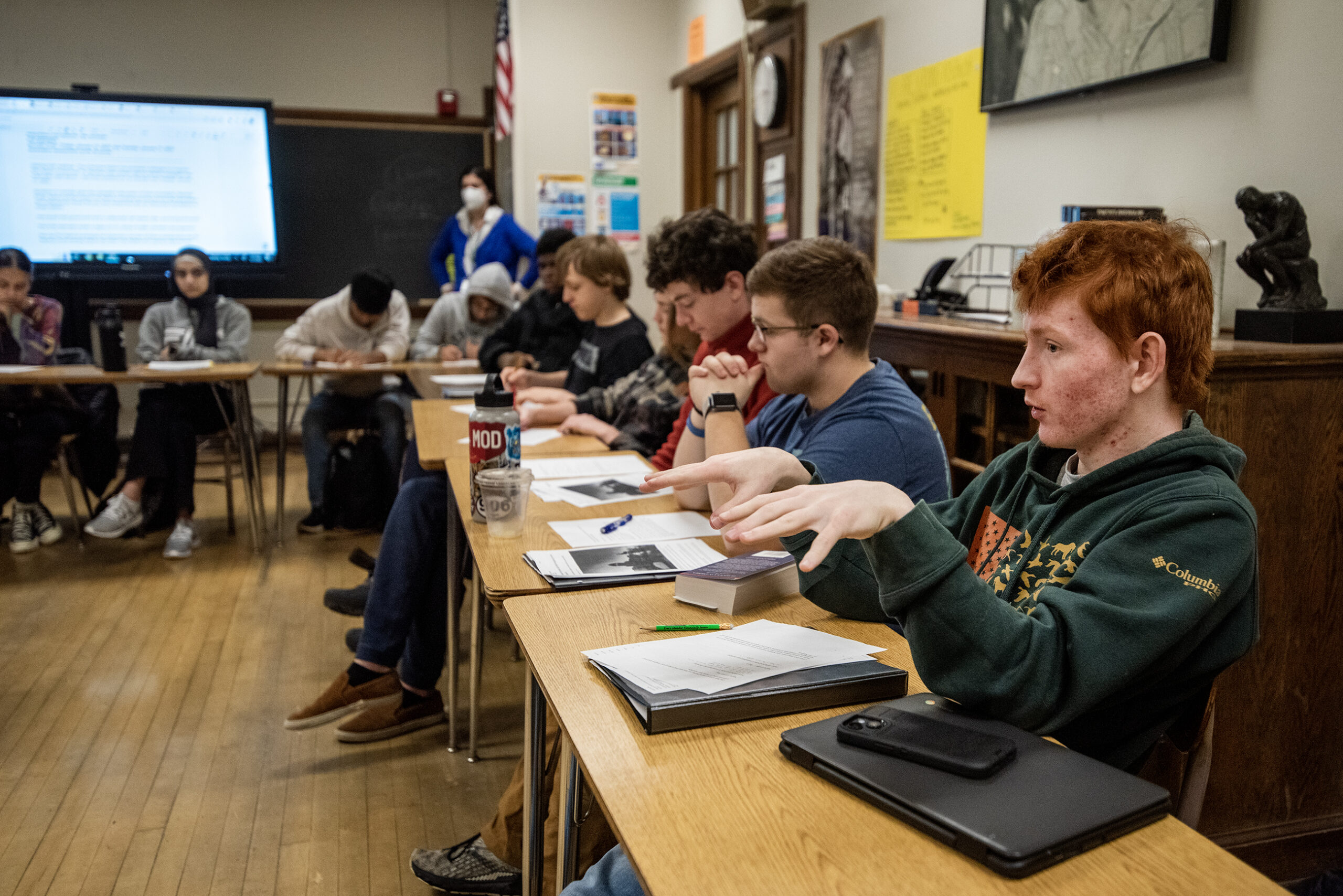

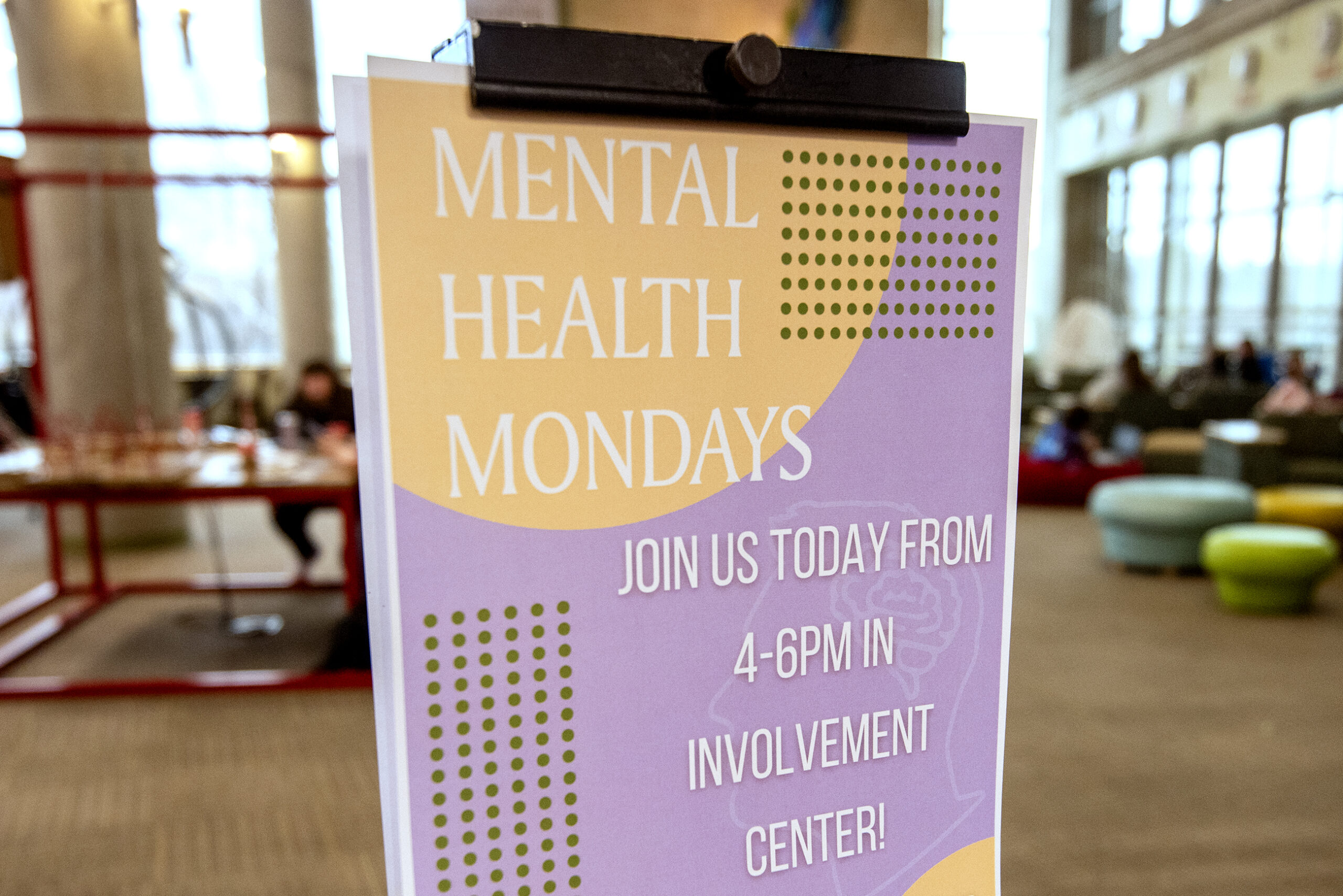

It’s another Mental Health Monday on the campus of University of Wisconsin-River Falls.

About 30 students are gathered at the University Center. Some are making aromatherapy oils or spinning a wheel to win a sleep mask. Others are coloring in small groups or doing their homework sitting on bean bag chairs. A four-person swing set is in the middle of the bright room.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The theme of this Mental Health Monday is “sleep.” Since the pandemic, students across the country have reported having more mental health issues. Counselors at UW-River Falls want students to understand relaxation and healthy sleep habits are linked to happier lives.

These student gatherings are part of the university’s response to deaths that have deeply affected members of the 5,000-student campus.

In the fall, four UW-River Falls students died by suicide in less than two months. Since then, students and campus leaders have taken steps to try to keep any more students from dying. But they have sometimes disagreed on how best to move forward.

Students said they’re happy to have Mental Health Monday. And they appreciate the therapy dogs the school has brought in.

But they’re looking for more.

“I think it’s a great way to bring people together, but nobody talks about the suicides that happened last semester,” said Chloe Skille, 19. “It’s understanding that people want to heal. But also, it’s still something that happened and affected a lot of us and it’s just not being talked about at all.”

A challenge for campus: how to heal without ‘romanticizing’ deaths

Losing four students in the course of just eight weeks to suicide shook the campus community in an unprecedented way.

Sophomore Isabella Chavira died on Oct. 3; junior Sabrina Hagstrom died Oct. 31 and freshman Jasmine Petersen died Nov. 3. The three women’s obituaries said they had each struggled with depression and took their own lives.

While the students were on an extended Thanksgiving break to mourn the deaths, a fourth student, Mason Crum, died on Nov. 26.

Scientists and public health professionals have long studied suicide “contagion” effects, where suicidal behavior can be transmitted from one person to another. Campus officials said the students’ deaths were not directly linked, but the campus still treated them as a suicide “cluster” since they all came from the relatively small population of students.

In the new semester, UW-River Falls leaders encouraged students to attend Mental Health Mondays, made counseling services available and even took steps to identify students on campus who could be at risk.

After the deaths, students created a memorial wall on the west end of campus, filled with flowers and handwritten notes remembering their friends.

But the students’ own desire to express their emotions and their grief sometimes conflicted with what health professionals said are best practices for stopping the spread of a suicide cluster.

When they returned from winter break in January, they were surprised to see the memorial had been removed.

Skille said the removal of the memorial made her feel “empty.”

RJ Forga, 19, said the memorial was a place where students could sit with their emotions.

Campus administrators said they were following best practices to avoid suicide contagion. One mental health resource said research has found language “glamorizing or romanticizing” suicide “may inadvertently make suicide seem desirable to other vulnerable young people.”

For some students, though, it felt like administrators were cutting off their ability to discuss the deaths.

Forga was nervous to return to school in January. But he said he felt better after a few weeks when he realized campus still felt like the supportive community he remembered.

“People heal and grow after such a loss, but no one wants to forget about it,” Forga said. “People are healing and doing what they need to do. But we’re ready and willing to have these conversations.”

Campus has bolstered support systems

In October, UW-River Falls Chancellor Maria Gallo put together an emergency operations committee, similar to what the university created during the onset of the pandemic.

The university is also working with national organizations to put together plans for preventing and responding to suicide attempts or events.

Gallo said the university is not stopping students from having conversations about those who died. But she did say they are more appropriate in smaller groups. That’s not only about concern over suicide contagion, she said, but also out of sensitivity to the families affected.

“I think there are support systems, and they certainly can talk about them,” Gallo said. “But to mention their names, time and time again — you know, something they don’t think about are their families and their survivors and how they feel about it. It’s obviously very personal and tragic and I think sometimes the students don’t realize that’s how it has to be, to respect the families.”

On a 5,000-person campus, many of the students knew at least one of the people who died last year.

Jennifer Ponchzoch and Annie Loss, both 20, had classes with Isabella Chavira and Sabrina Hagstrom.

Ponchzoch and Loss were also in Hagstrom’s dorm.

“Actually, our last conversation was what resonated with me the most,” Ponchzoch said. “We talked about the afterlife and what heaven was like.”

Loss said she was worried about returning to school this semester because of her own struggles with mental health. She’s a biochemistry major and said the pressure is sometimes too much to handle.

“Classes are extremely difficult, and every class I go to the harder they get and I feel dumber and dumber,” Loss said. “Mental health-wise, it’s still really challenging to get through.”

Nation has seen years of increasing deaths by suicide

The mental health crisis UW-River Falls is dealing with is not unique to the campus. It is mirrored across the state and country.

Suicide rates among adolescents were on the rise, but the pandemic significantly increased the number of young people taking their lives.

The suicide rate among people aged 10 to 24 remained stable from 2001 through 2007 and then increased 62 percent from 2007 through 2021.

A recent survey from the state’s Office of Children’s Mental Health found one in 10 Wisconsin teens attempted suicide last year.

The report found key stressors for youth are academic pressures, along with societal issues unique to their generation including widespread gun violence, climate change and deep political divisiveness.

Loss says her friends and her parents help her deal with anxiety and mental health struggles.

Ponchzoch has been using campus mental health services.

“I think the campus is trying their hardest to show the students that they have so many things that can help them,” Ponchzoch said. “We have the therapy dogs, we have the counselors and we have the mental health days. They are trying to make sure the students are happy and healthy.”

Loss agreed, but worries about the future.

“It just feels as though we’re trying so hard to get everybody to the mental spot that they are, but once we get there, we’re not going to focus on the mental stuff as much,” Loss said. “I just hope this continues.”

If you are struggling with thoughts of suicide, call 988 for the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also text HOPELINE to 741741 for the free and confidential Crisis Textline.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.