The psychedelic revolution in mental health treatment is on the way, with Food and Drug Administration approval likely in just a few years — which means that before long, the treatment of choice for depression and addiction could be a hallucinogen like psilocybin.

When that day comes, we’re going to need a lot of mushrooms.

But in Wisconsin, a non-profit drug manufacturer is gearing up to synthesize enough medical-grade hallucinogenic molecules to supply the world.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Usona Institute is a nonprofit medical research organization in Madison with big ambitions in the world of psychedelics — they’re at the forefront of trying to get psychedelic compounds approved for therapeutic use.

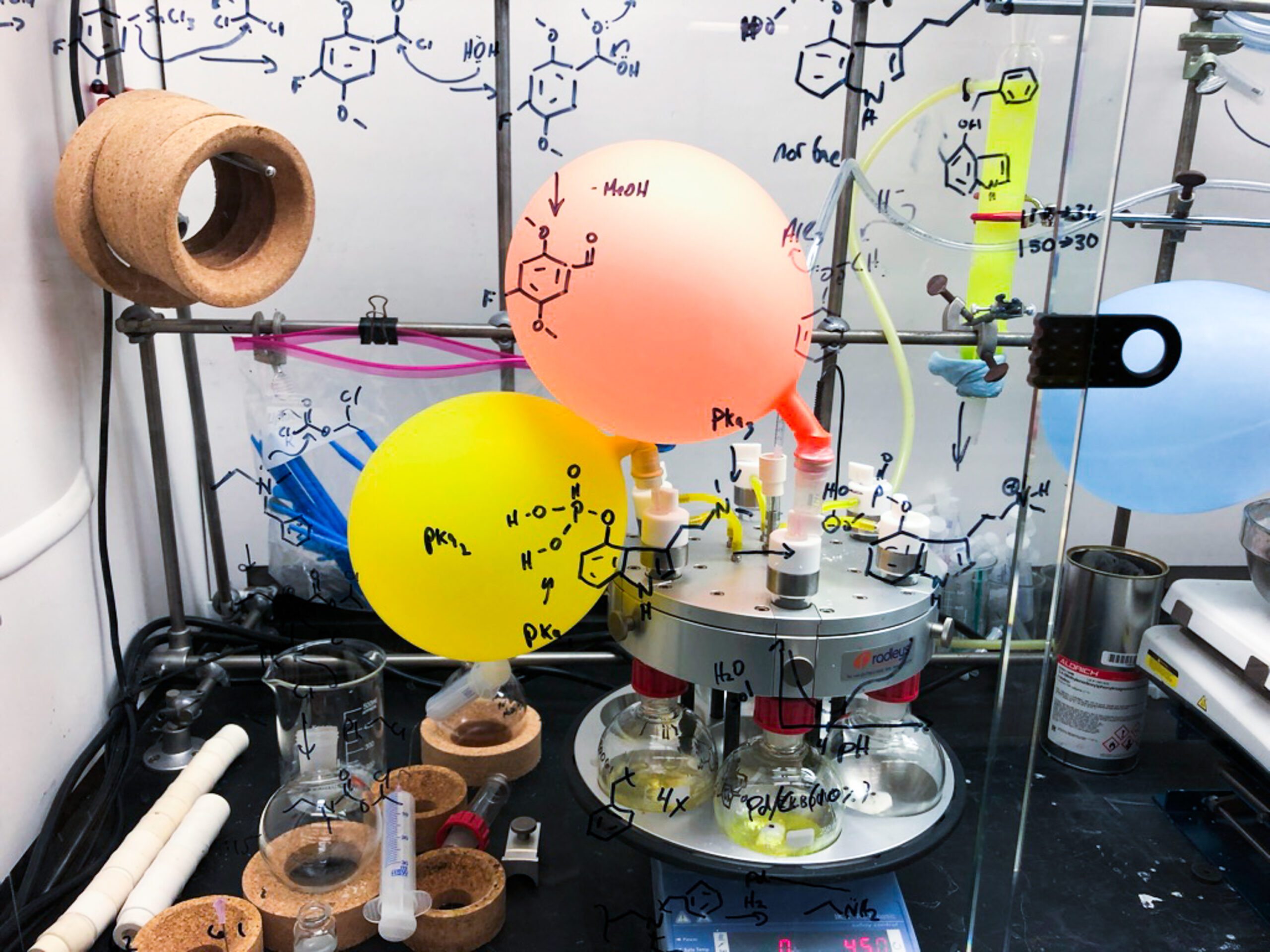

Medicinal chemist Alex Sherwood showed Steve Paulson around Usona’s research and development lab for an episode of “To The Best Of Our Knowledge.” Here, Sherwood and his colleagues are examining compounds that produce psychedelic experiences — like psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, or 5-MeO-DMT, which is found in Sonoran toad venom.

The goal is to better understand the basic chemistry of how psychedelic compounds work — and eventually to synthesize them, and even create new ones. Sherwood says psychedelics share numerous common features, but the differences between them are under-researched.

“If we look at the natural products of mescaline, which is found in peyote cactus; or dimethyltryptamine, which is found in numerous places; mimosa hostilis root bark; or even lysergic acid amide, these are all the different structural classes of psychedelics. And they all produce similar effects, but they’re all different in some ways as well,” says Sherwood.

In the case of synthetic psilocybin, Sherwood says chemists can’t compete with nature — what they’ve created is an exact replica of the compounds found in a mushroom harvested from the forest.

“There are no mushrooms anywhere in the lab. We synthesize the psilocybin from basic commercially available building blocks,” says Sherwood. “I like to say nature is always the best chemist.”

“These represent all of the building blocks that we would use to make new compounds. It’s like being in a well-stocked kitchen.”

It helps to keep Mother Nature’s work handy for research and development purposes. Alex ushers Steve over to a safe that is filled with capsules of different psychedelic compounds. He points to one bucket that contains 2000 capsules of psilocybin. There’s also MDMA, mescaline and LSD.

Sherwood and his colleagues use the psychedelic compounds as a jumping off point, seeking to tweak the original recipe to better suit clinical use.

“What we do is take a look at that structure and say, okay, well, what if we put a carbon atom over here? Or what if we put a bromine on this part of the ring? Or what if we substituted a nitrogen into this part of the molecule? And then you test it,” Sherwood says.

This playful spirit of discovery seems to permeate the lab, and colorful drawings of molecules scattered around the space certainly add to that feeling.

“It’s like Legos, right? You want to build something with a shape,” says Sherwood. “So you’re going to reach into that bucket and make sure you connect the right Legos in the right places. It’s like connecting things that want to stick together to make a shape.”

‘A whole new way of thinking about mental illness’

Where will all this lead? FDA approval, and eventually, mass production, according to Usona Institute co-founder and Promega Corporation CEO Bill Linton.

Linton discovered psychedelics and their capacity to alter our thinking and perception during his college days at the University of California, Berkeley in the 1960s. Many years later, he became particularly interested in the clinical potential of psychedelics when a neighbor sank into a deep depression in the midst of her terminal illness. He read up on the work of psychopharmacologist Roland Griffiths at Johns Hopkins University, and got her enrolled in a study of how psychedelic experiences could erase the sense of dread for people facing death.

“She was there for about a day and a half, and when she came back, I could see that something fundamental had changed,” says Linton. “This sense of impending doom and sadness had lifted and instead there was this joy in embracing every day with a sense of gratitude.”

Though she only lived for a few months after that, his neighbor’s experience propelled Linton to connect with the latest wave of researchers examining psychedelics and their impact on mental health and human perception.

“I think we’re probably three to four years away from approval,” says Linton. “The FDA’s No. 1 concern is safety because once a drug is approved, they can’t just go in and withdraw it from the market.”

To hear more about how psychedelic experiences affect mental illness — and why Linton thinks wider availability of psychedelics could be a revolutionary change in how we treat it — check out the full conversation that Steve Paulson had with Linton for “To The Best Of Our Knowledge.”