Bill Linton is on a mission. He believes psychedelics could revolutionize the treatment of mental illness — from depression and addiction to PTSD — and he’s working with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to get approval for psychoactive compounds to be used therapeutically. And he has the resources, the ambition and the scientific know-how to help make that happen.

A chemist by training, Linton is the CEO of Promega Corporation, a biotech company based in Madison, Wisconsin, that he started in 1978. It now has 1,900 employees, with branches around the world and revenue last year of more than $750 million.

Then in 2014, he co-founded the nonprofit Usona Institute, a medical research organization with a particular focus on getting psychedelic therapies through the lengthy process of approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

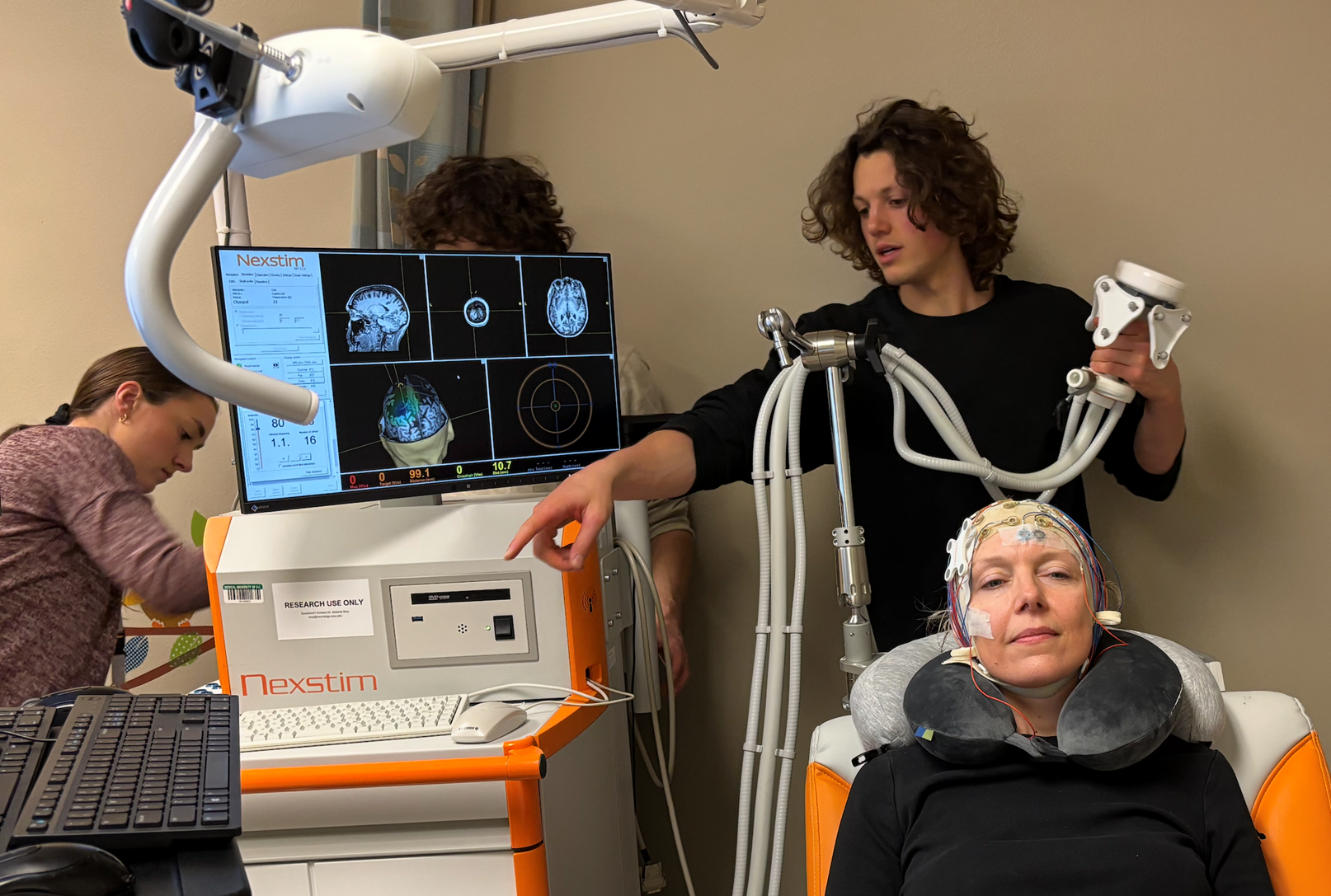

Usona Institute is poised to become a global hub for all things psychedelic. It’s currently building a 93,000-square foot structure devoted specifically to psychedelics, with the ultimate aim of launching the coming psychedelic revolution. Usona is already manufacturing large quantities of synthetic psilocybin for use in clinical trials around the world and also studying the impact of psychedelic therapy.

Linton’s name rarely comes up in news stories about psychedelic research, but he’s funded and facilitated many of the studies. He prefers to stay behind the scenes, playing the role — as he puts it — of “stagehand.”

Recently, Wisconsin Public Radio’s “To the Best of Our Knowledge” sat down in his house for a rare in-depth interview about his own history in the psychedelic movement and his deep interest in the nature of consciousness. For Linton, it all started in the 1960s when he was in college at the University of California, Berkeley, where everything seemed possible.

This interview, which aired on TTBOOK, has been edited for length and clarity.

Bill Linton: I got to Berkeley in the spring of 1967. That was where there was really an awakening to the power of psychedelics, amongst other things. The free speech movement had preceded that, the Summer of Love, and I just thought, something is going on here.

One day, some people I had met just said, “Hey Bill, do you want to try LSD?” It was around 6 or 7 in the evening, and there was a Harley-Davidson chopper, this absolutely beautiful, immaculate, all-chrome chopper. As I just stood there and watched, it started to shape-shift and it just came alive. And this woman said to her boyfriend, “I think we need to get him home.”

We walked a couple blocks to my apartment and they stayed with me there for the evening, but I spent most of the time just by myself in my bedroom. It was one of the most remarkable experiences of my life. Following that, I felt that something fundamental had changed in how I perceived the world.

Steve Paulson: I’m guessing you wanted to take more LSD after that experience.

BL: Yeah, and over the next three years, I did maybe up to a dozen times, and then at some point I thought that was nothing I needed to do further, but if this was something important to pursue, that I could come back to it later. And it was three decades before that happened.

SP: That was the first psychedelic renaissance in the 1960s. But then it all came crashing down and psychedelics were made illegal. But once again, there’s a flourishing of interest in psychedelics. How would you describe where we are right now?

BL: There was a reawakening for me as well. And this really came from observing a neighbor who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

Betty really went into a deep depression and just had a lot of fear. It reminded me, though, that there had been work done back in the 1960s to help people who had been diagnosed with a terminal illness, where LSD or some other psychedelic had helped them see life and death in a different way. I came across the work of (psychopharmacologist) Roland Griffiths at Johns Hopkins University. Betty applied to get into his program and about a month later, she was in Baltimore at the treatment center.

She was there for about a day and a half, and when she came back, I could see that something fundamental had changed. This sense of impending doom and sadness had lifted and instead there was this joy in embracing every day with a sense of gratitude.

SP: This was psilocybin?

BL: Yes. She only lived another three or four months. And while the impact on her was enormous, I would say the impact on her family and friends was even greater — this ripple effect of (spending) each day in a state of grace.

That reawakened in me the sense that maybe this is the time to reengage and see what’s going on. So I got to know the researchers in the field and then that just progressed over time.

SP: How do you explain what happened to your friend? Why would this single experience with psilocybin be so transformative?

BL: My opinion is that it opens a level of awareness that we don’t normally perceive. In some way these molecules — which are very similar to serotonin — unlock perception that enables us to not only see, but to actually perceive in different ways.

The fact that a molecule, just one time, can change a person’s view of life and death itself is remarkable.

SP: That’s astonishing. How is that possible?

BL: I don’t think people know. And that’s one of the mysteries of the work that’s still going on.

SP: It sounds like you’re saying that for all the scientific research on psychedelics over the last decade, there’s something about this experience that’s ineffable. Science runs up against a wall as to what it can explain.

BL: Yeah, at least at this point it does.

An analogy would be if we live in a world where, like dogs, we can only see in black and white and shades of gray. And one day, someone gave you a capsule and for four or five hours you could see color. Then you went back to baseline and your friends gathered around you and they said, “Steve, tell us what you experienced.” How could you describe what a color is to people who had never seen a color?

And this is one of the challenges for people trying to describe their experiences. They really don’t have the words to describe exactly what they were able to experience during that time.

Seeking FDA approval

SP: A lot of people believe the federal government will legalize psilocybin for treating depression, and other psychedelics will be used to treat addiction and PTSD. How close is FDA approval?

BL: I think we’re probably three to four years away from approval. The FDA’s No. 1 concern is safety because once a drug is approved, they can’t just go in and withdraw it from the market. People are able to prescribe it and they’re able to use it. So before it gets there, the FDA is going to ensure that it has gone through every step and every box is checked.

I think the efficacy question is going to be easier to answer because the studies that have been done — whether it’s on depression, anxiety, addiction — show a pretty strong signal of improvement.

SP: Isn’t psilocybin more effective in treating depression than the SSRIs — the traditional antidepressants like Prozac?

BL: They are, because the SSRIs tend to numb a person to whatever’s causing the depression. SSRIs have a neutralizing effect, but they don’t really get at the underlying reason for depression.

SP: But why would psilocybin be able to treat the underlying cause?

BL: This is such an unusual approach to medicalizing a treatment because we always want to know what has actually changed physiologically. Years ago, many of the research scientists and psychiatrists thought, “Well, there still have to be a few of those molecules dancing around in a person’s brain months after.”

But it turns out, no, it’s pretty much all gone out of the system within about 10 to 12 hours. But something has changed.

It’s not this massive rewiring of the brain; it’s the experience itself, which stays with a person for a lifetime. Just like I remember the experience I had back in 1967. I recall elements of that experience today as though it had just happened. It’s that remarkable.

SP: But not everyone wants a mind-blowing psychedelic trip. Is it possible to get the same therapeutic benefits from taking psilocybin without actually going through the experience itself?

BL: There are now studies to give someone psilocybin during a deep sleep state. Can a person with no conscious memory of the experience still have a positive outcome? There’s a group at the University of Wisconsin-Madison that’s giving individuals midazolam, which erases memory. But the problem they’ve had so far is that people still remember the psychedelic experience.

SP: Even though they’ve taken this drug to try to wipe out their memory?

BL: Yeah, for some reason, they still remember. So they haven’t quite gotten to where they want to go on that, but it’s an area of deep interest: could you create a scenario where somebody would have the drug and have no psychedelic experience, but it would still end up being effective on the treatment of depression? I’m skeptical that this can happen because I don’t think it’s possible to work through a positive outcome for depression, addiction, or anything else without the experience — but that’s my hypothesis.

The psychedelic gold rush

SP: What is the goal of your psychedelic institute, Usona?

BL: The ultimate goal is to provide the pathway and the means for an awakening through these drugs.

SP: So not necessarily treating only mental illness? You’re talking about something bigger — an awakening.

BL: I am. And while the FDA will only approve something that is treating a disease state, I think in the long-term, there will be opportunities for these treatments to be available to more than just people who have been referred by a psychiatrist for some mental illness.

SP: Do you worry about this? These are powerful substances.

BL: I’m concerned that people will potentially use them in ways that are not productive. But I also think there’s enough concern that nobody wants to see what happened back in the 1970s when everything was made illegal. But of course, once momentum builds — and particularly if there’s money to be made — then boundaries get crossed and it’s not always the best outcome.

SP: Well, let me ask about the money to be made, because there is a gold rush right now. There are a lot of startup companies, with venture capital, wanting to cash in on this new psychedelic revolution. The fear is that this will become one more tool in the Big Pharma toolbox. What do you make of this?

BL: I think the fear is monopolization to the extent that a pharma company or for-profit organization will be so intent on trying to control the field that they’ll take the steps to have that control in a way that’s not productive.

SP: Would they have to claim intellectual property rights?

BL: Exactly. For example, there are companies that have gotten patents issued that probably should not have been issued, but it was because patent offices just simply didn’t have the information in hand to deny the claims of the patent. I think that’s changing because there are an increasing number of groups, Porta Sophia being one of those…

SP: … a group that you started.

BL: Yes, together with patent attorneys, to make sure that information that has been in the field for decades is available to patent examiners. As they look at a claim, they can say, “Wait a minute, this has been out there for 10 years, 20 years.”

So we’re making a lot of information available primarily to patent examiners, but also to companies so that they’re not going to pursue patents that in the end are not going to get approved.

SP: So Usona is not trying to patent any of the drugs that you are manufacturing?

BL: The only reason we would patent something would be to ensure that nobody else patented it. So a strategy could be, for example, to file for a patent and then abandon the patent. But then you can either donate it to the public good or abandon the patent, and it basically means nobody else could patent it. That’s a bit of an odd patent strategy, but it’s something we’ve discussed.

SP: I would think there’s another problem with trying to cash in on psychedelics if you only need a single dose — or just a few doses — to get the therapeutic benefits. That’s a very different business model than getting a Prozac pill every day. The cost-benefit calculus for a psychedelic business is not so clear to me.

BL: It’s not clear to me, either. If you’re a typical pharmaceutical company, you want to create something that’s unique that you can patent and that is taken every day and then you charge quite a bit for it. This doesn’t fit any of those models.

So these molecules, the ones that we call the “heritage” molecules — psilocybin or LSD or DMT or 5-methoxy-DMT or mescaline — they’ve been around for a long time. They are generics by definition. And the fact that a single experience with one of them, or maybe a couple in a person’s lifetime, can have that kind of effect is not a good business model for pharmaceutical companies. That’s why you haven’t seen any major companies coming into the field.

SP: I realize all of this could play out in a lot of different ways, but 10 years from now, how do you think our system of treating mental illness might change?

BL: I think these molecules open up just a whole new way of thinking about mental illness. If you look at the underlying cause of addiction or mental illness or obsessive-compulsive disorders or eating disorders, my view is that a lot of it comes from a sense of disconnection. Psychiatrists sometimes call it a “spiritual break.” Often a person has lost their sense of meaning and purpose. When a psychedelic experience can reestablish that sense of connection and relationship, then these symptoms can begin to resolve themselves in a remarkable way. It’s going to change how people think about how we treat these illnesses, how psychiatrists treat them.

There’s an estimate of a billion people in the world that suffer from some form of addiction, depression, anxiety — things that have profoundly affected their ability to live a normal life. I think in 20 years, we’re going to look back and see that we’re still just planting seeds and we’re not quite sure where they are going to grow.

SP: You’re talking about a potentially revolutionary change in how we treat various mental Illnesses.

BL: Yes.

To read about how scientists at the Usona Institute are working to better understand the chemistry of psychedelics — with the ultimate goal of getting them approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration — check out our story about Steve Paulson’s visit to Usona’s research and development lab.