Milwaukee plans to address racism and health equity over the next five years by focusing on challenges like housing, maternal and child health and public safety.

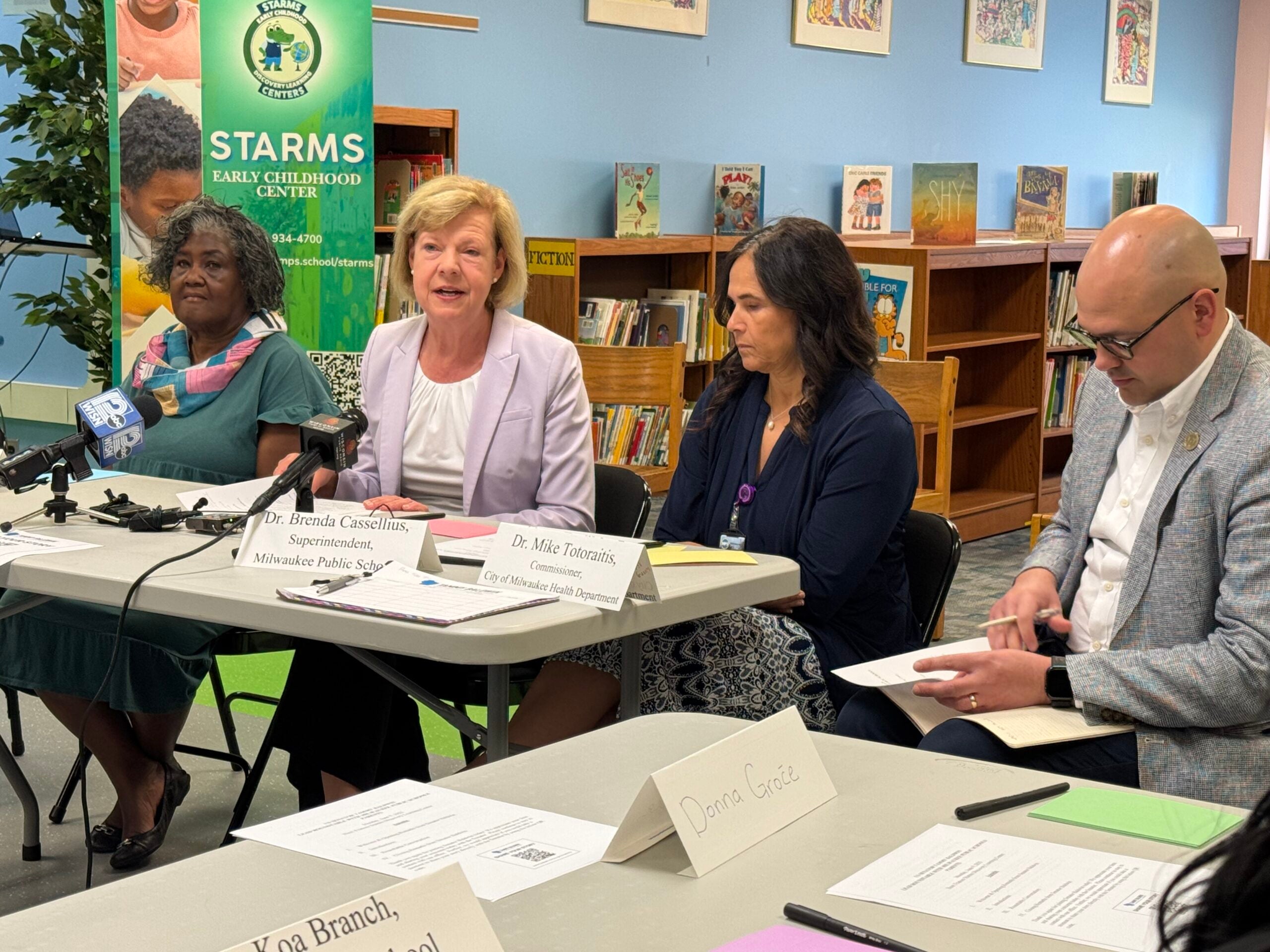

Those steps and others were outlined in the newest iteration of the MKE Elevate Community Health Improvement Plan announced Thursday by the City of Milwaukee Health Department. Report authors say their goal is to make Milwaukee the healthiest city in Wisconsin.

Officials said racism and health equity can be addressed by partnering with hospitals, businesses and nonprofits, which will work together to address three goals: creating healthy structures like housing, addressing maternal and child health disparities and fostering safe and supportive communities.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

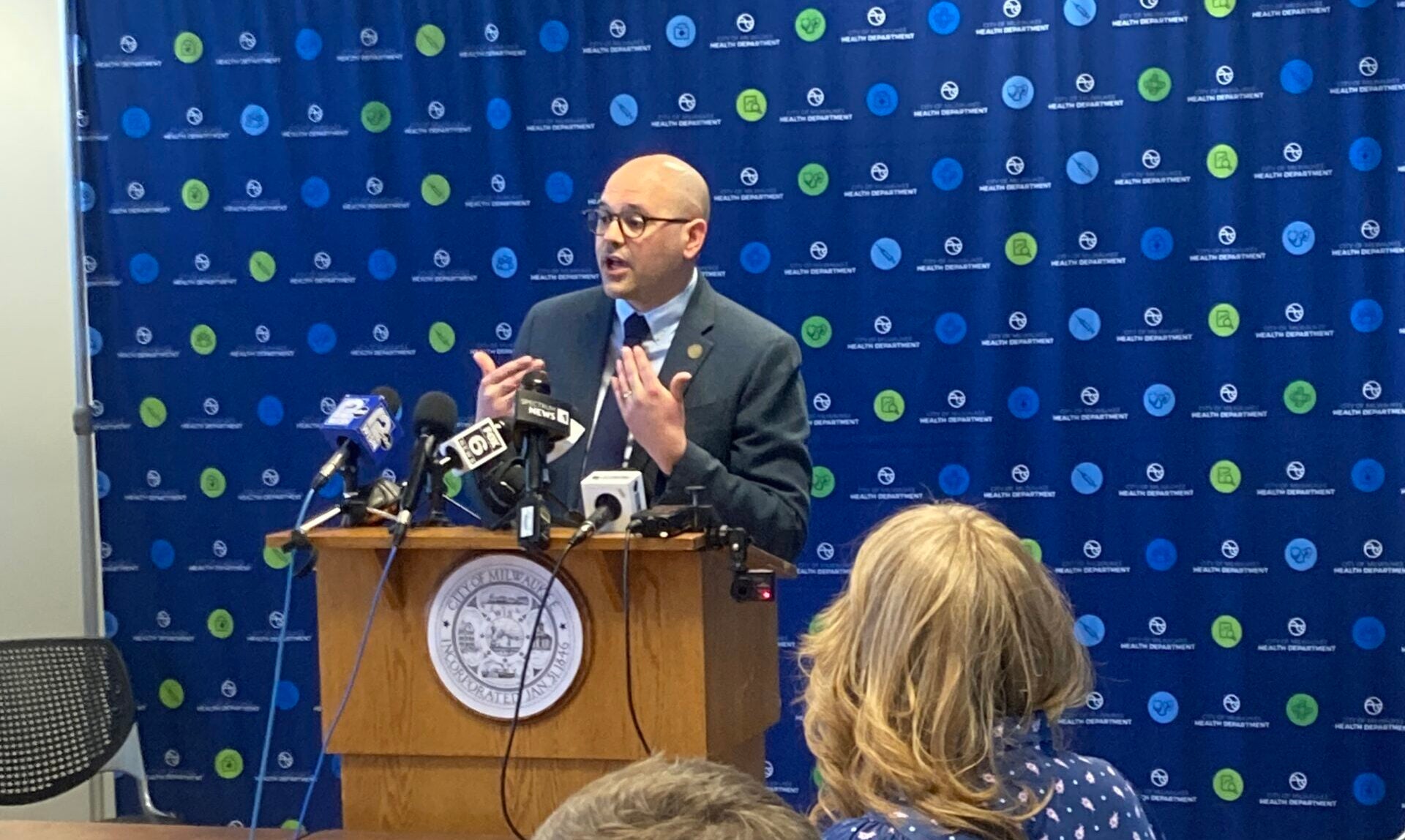

City of Milwaukee Health Department Commissioner Mike Totoraitis said the city must acknowledge it’s one of the most segregated in the country.

“We know that the color of our skin affects how we access different resources, partners and health systems,” Totoraitis said. “By naming health equity and racism as the overarching theme, that really calls on us to make sure that we’re prioritizing that issue within each of the different buckets.”

Each goal has objectives, strategies and implementation partners like community health organizations. So far, 61 groups have signed on to work toward the goals.

The plan is a result of data collection and community outreach, including approximately 2,000 survey results from Milwaukee residents collected over the last year.

The previous plan “failed to be implemented” in large part because the pandemic redirected resources. But Totoraitis is hopeful this iteration will be effective because of how it was designed.

“We were very intentional and deliberate with making sure we were in the right spaces to talk to the right people,” Totoraitis said.

Nichole Logan is with the Wisconsin Association for Perinatal Care, an implementation partner. She is working with hospitals to improve the care for pregnant and postpartum people with substance use disorders. She said the plan resonated with her because, like care, it is all-encompassing.

“You’re not just caring for a pregnant person, you’re caring for a pregnant person with all these other things going on in their life. And you need to be holistic when you are addressing them,” Logan said.

First goal: Create a healthy ‘built environment’

Report authors say Milwaukee’s history of segregation has created persistent racial inequities, arguing projects like the construction of the Interstate 43 freeway through Bronzeville played a role in the destruction of thriving Black neighborhoods.

The plan says addressing these inequities requires a healthy “built environment,” which includes human-made structures like buildings, roads, trails, parks and houses. To improve these structures, the plan outlines strategies to improve housing conditions, expand access to healthy food, and increase the number and quality of transportation options and recreational spaces.

According to the report, almost half of renters in Milwaukee spent at least 30 percent of their income on rent in 2021. Authors said the city needs to improve pathways to homeownership by growing down payment assistance and prioritizing affordable housing construction.

The report also cited data that shows food pantries and assistance with getting groceries was one of the top unmet needs in 2021.

Second goal: Address maternal and child health disparities

Melissa Seidl, public health strategist with the health department focusing on maternal and child health, said maternal and child health disparities affect every other part of the plan.

“It really touches every aspect of our lives. This is our families, these are our neighbors as we live and grow throughout that pregnancy stage,” Sidl said.

According to the health department, the infant mortality rate in Milwaukee is among the worst in the U.S., disproportionately harming people of color. Black infants die at a rate three times greater than non-Hispanic white infants.

To address these disparities, the plan details strategies to improve health outcomes for birthing people and babies, including expanding access to high-quality reproductive health care that is culturally appropriate and offered by diverse providers.

“Everyone feels safe and represented by their provider so that everyone feels welcomed and a sense of belonging in that health care system as they go through their pregnancy and family journey,” Seidl said.

Final goal: Foster safe and supportive communities

The city’s report also calls for creating safe places for everyone to live, work, play and learn. Strategies include decreasing interpersonal violence, crime, reckless driving, substance use and improving mental health.

In 2021, a Black, non-Hispanic Wisconsinite was nearly 32 times more likely to die from homicide than a White, non-Hispanic Wisconsinite, according to the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

In Milwaukee County, drug-related deaths have increased 67 percent between 2019 and 2022, according to the health department.

Speaking to the crowd at an event celebrating the plan, Milwaukee Mayor Cavalier Johnson said that collaboration between the health department and implementation partners is key to executing this plan, especially since Milwaukee declared racism a public health crisis in 2019.

“No one person, no one organization, no government can take the task of improving the health of our community alone,” Johnson said. “It is going to take all of us to create change.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.