With school out, many parents and guardians are spending more time with their children — which presents an opportunity to check in on their mental health.

Youth mental health concerns have been on the rise for years. Before the pandemic, about 60 percent of high schoolers in Wisconsin were experiencing anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation. Although it’s difficult to quantify how the pandemic affected kids’ mental health, experts say that isolation, disconnection from school and friends, family financial stresses and the illness and death of loved ones exacerbated children’s mental health concerns.

In the first few months of the pandemic, there was a 24 percent increase in mental health emergencies for kids ages 5 to 11, and a 31 percent increase for ages 12 to 16. LGBTQ+ youth are twice as likely to experience anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation as their non-LGBTQ+ peers.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The end of the school year can be a double-edged sword for students, said Linda Hall, director of the state Office of Children’s Mental Health. It can bring relief from academic pressures, bullying and lost sleep time, but it may also mean students are disconnected from many of the friends, trusted adults and activities they rely on during the school year.

“If you sense that’s happening with your kids, I would say look to your community,” she said. “Where are the places that your kids can gather with other kids in the community, so they can help each other out, and maybe there are also some supportive adults there who help to ground them and give them some ideas about how to be healthy and safe.”

To tie in with the recent release of a two-part PBS documentary on children’s mental health that centers on kids’ experiences, Hall and the Office of Children’s Mental Health highlighted best practices and resources for helping kids manage their mental health and stay connected to their communities.

Making space at home

Hall said adults should make space to listen to their children every day.

“Create a space, even if it’s a few minutes, with no agenda, no judgment, just be open to listen,” she said. “They may not say much at the beginning, but soon, they will start opening up to you.”

A recent study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison showed that adults’ habits also heavily influence how their kids behave, especially around technology.

“We need parents to model putting down your phone and your screens and engaging with your kids,” Hall said. “Whether that’s going outside to play a game, having a meal together where you talk and the phones are in another room, those are all important things to identify.”

She said adults also need to be in touch with their own mental health. When they aren’t assessing the emotions and experiences that they’re bringing to the table, they risk interpreting their kids’ actions or feelings not based on the children, but based on their own issues.

“We also need better access for parents to mental health and substance abuse treatment, because we know there are parents out there who don’t have access to that kind of treatment,” she said. “Their impairment is affecting their children.”

Resources at the school, state and national level

Hall noted that the majority of children who are getting mental health help get it through school, and while some districts are able to continue those services through the summer, many are not. Some schools also cannot afford counselors or school psychiatrists to meet their students’ needs — or, even if they can afford them, cannot find people to fill those roles.

If parents see concerning changes to things like sleep, diet or their kids’ interactions, Hall said their first resource should be the family’s pediatrician or general practitioner, However, only 55 percent of children in Wisconsin have a “medical home,” or a family-centered personal doctor or nurse they use for illness and wellness visits, so that option is not available to all families.

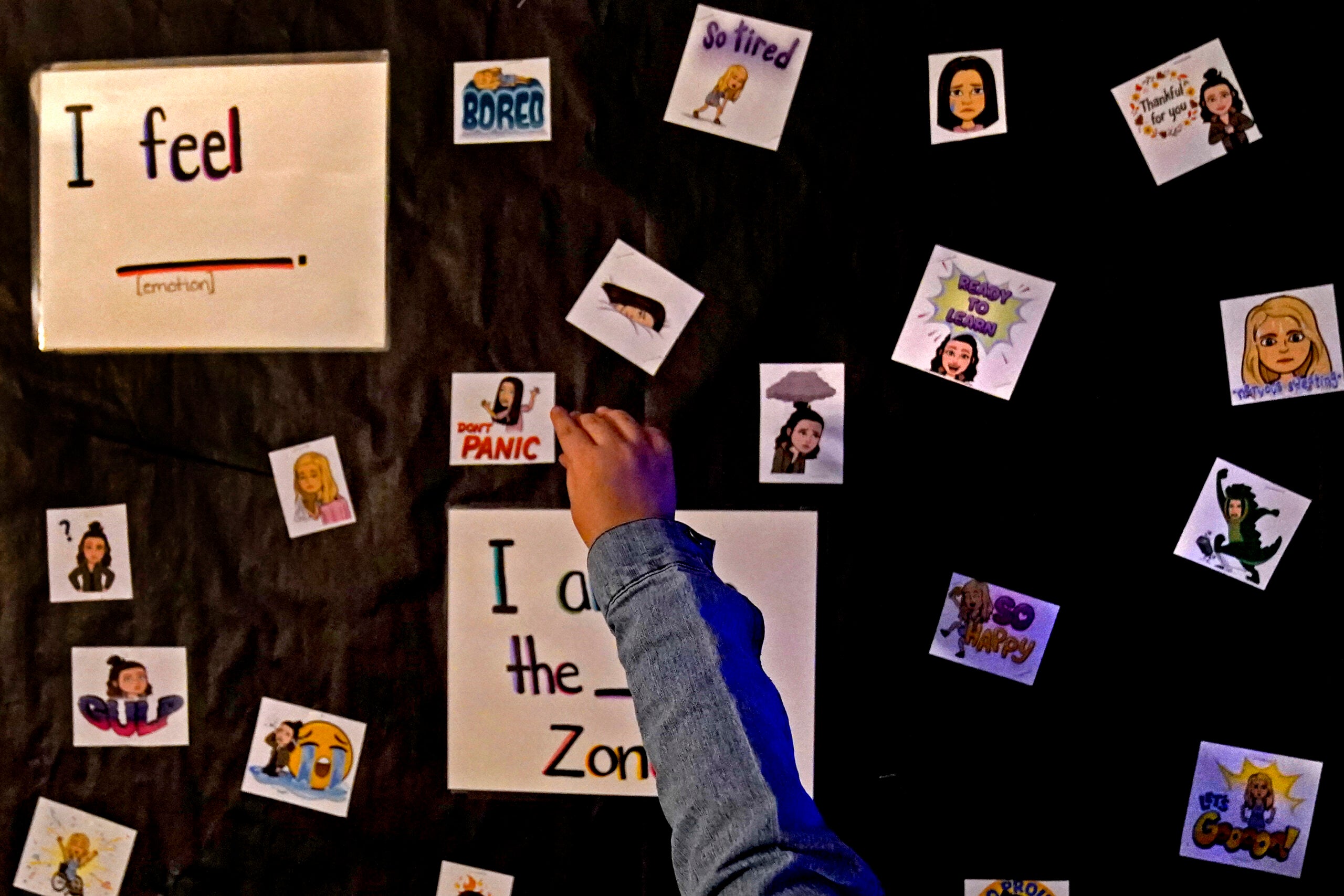

The Office of Children’s Mental Health website has several resources, including a “Feelings Thermometer” that helps kids — and their adults — understand how they’re doing.

The site also has mental health crisis cards, children’s mental health service guides and fact sheets for various questions around children’s mental health.

A national hotline for mental health services, 988 — modeled after 911 — is set to launch later this month. Hall said Wisconsin got a head start in centralizing its services, and should be able to use the hotline to connect families to services when it launches.

Mental health services are irregular, but students want to help

Many school and community-based mental health services for children are grant funded, which can often mean they’re at risk of disappearing if funds run out. With an influx of federal dollars through several rounds of coronavirus relief funding, some schools were able to put more money into mental health services — but that, too, is time-limited, as pandemic relief dollars need to be accounted for by 2025.

“These programs are very helpful, and make a difference, but we need them to be funded in an ongoing way,” Hall said.

Children who are struggling with their mental health start experiencing symptoms of emotional distress, on average, for 11 years before they are treated. Hall said in-school mental health programs can help ease their symptoms while they wait for treatment.

“We know that, in behaviors, kids are showing us what they think,” said Hall, pointing to reports of increased expulsion from preschools and more disciplinary issues at school. “What we need to do is get behind those behaviors and try to understand, what is this child trying to communicate to us?”

One tool, she said, is youth-based mental health organizations, of which there are 135 that the Office of Children’s Mental Health has identified in Wisconsin. They include “Raise Your Voice,” “HOPE Squads” and “SOS.”

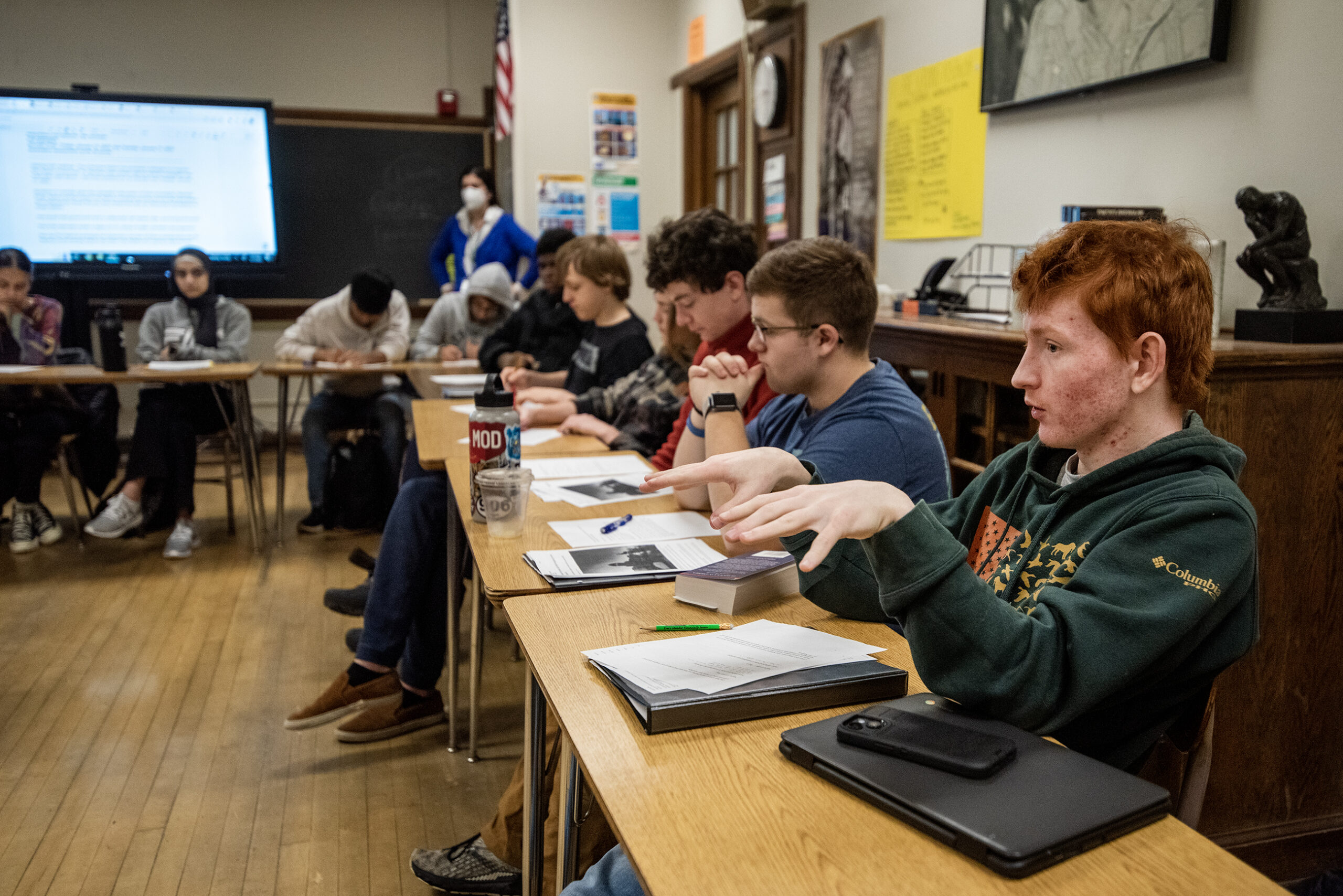

“We hear from the youth that we have talked to in listening sessions and in other work groups that they believe that we need to be doing more about mental health literacy,” she said. “They have ideas, and they want to be in the lead about addressing it at school.”

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, call the suicide prevention lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text “Hopeline” to 741741.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.