Shonita Roach experienced her first bout of postpartum depression when she was 21 years old.

While grieving the loss of her firstborn son, the birth of her second son brought on tears and a sense of withdrawal. She said she felt as if she was being “swallowed by a sinkhole.”

“I struggled and did not recognize it was postpartum depression, because there was not enough information circulating,” Roach said on Wisconsin Public Radio’s “The Morning Show.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

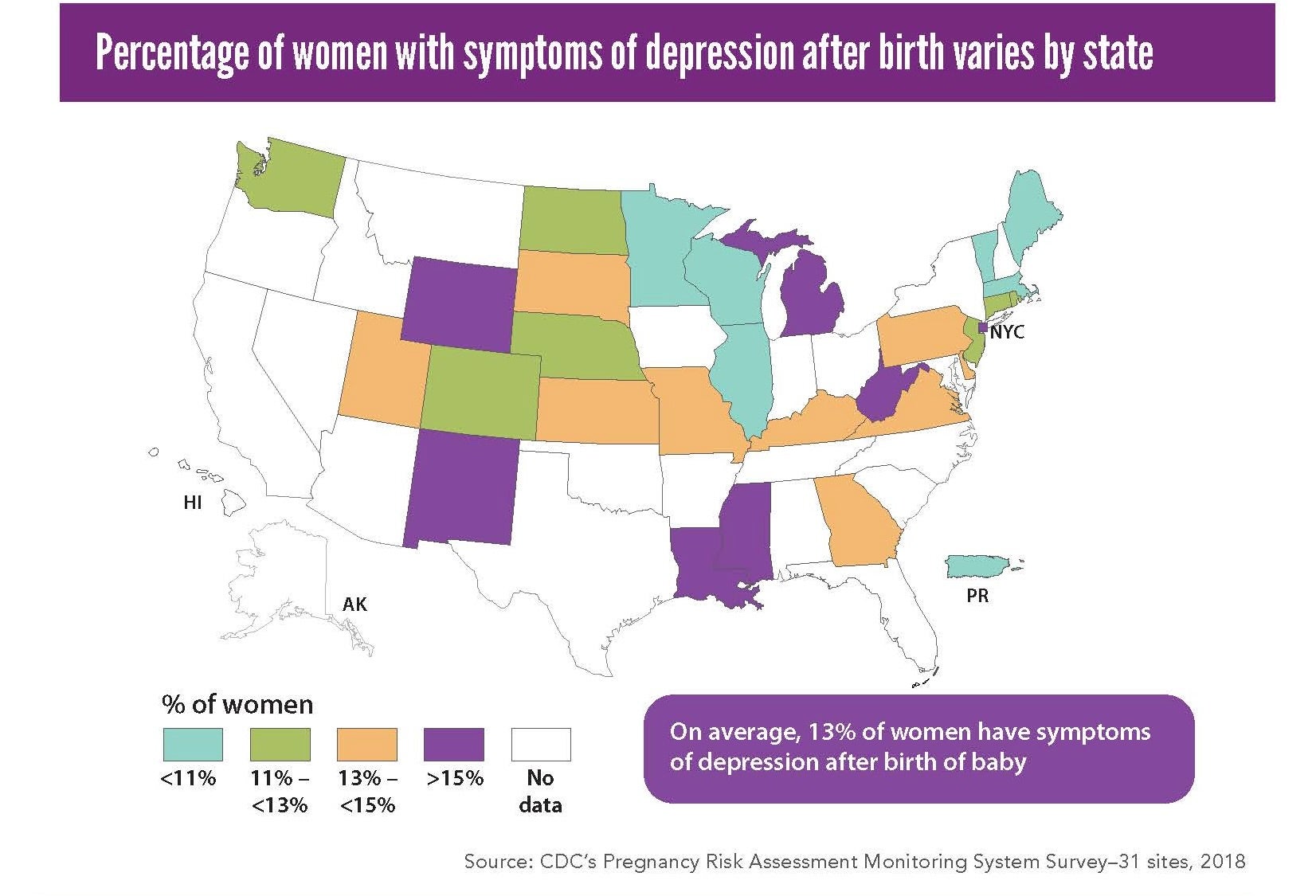

About 1 in every 8 women report experiencing postpartum depression. It is one of the leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Protection.

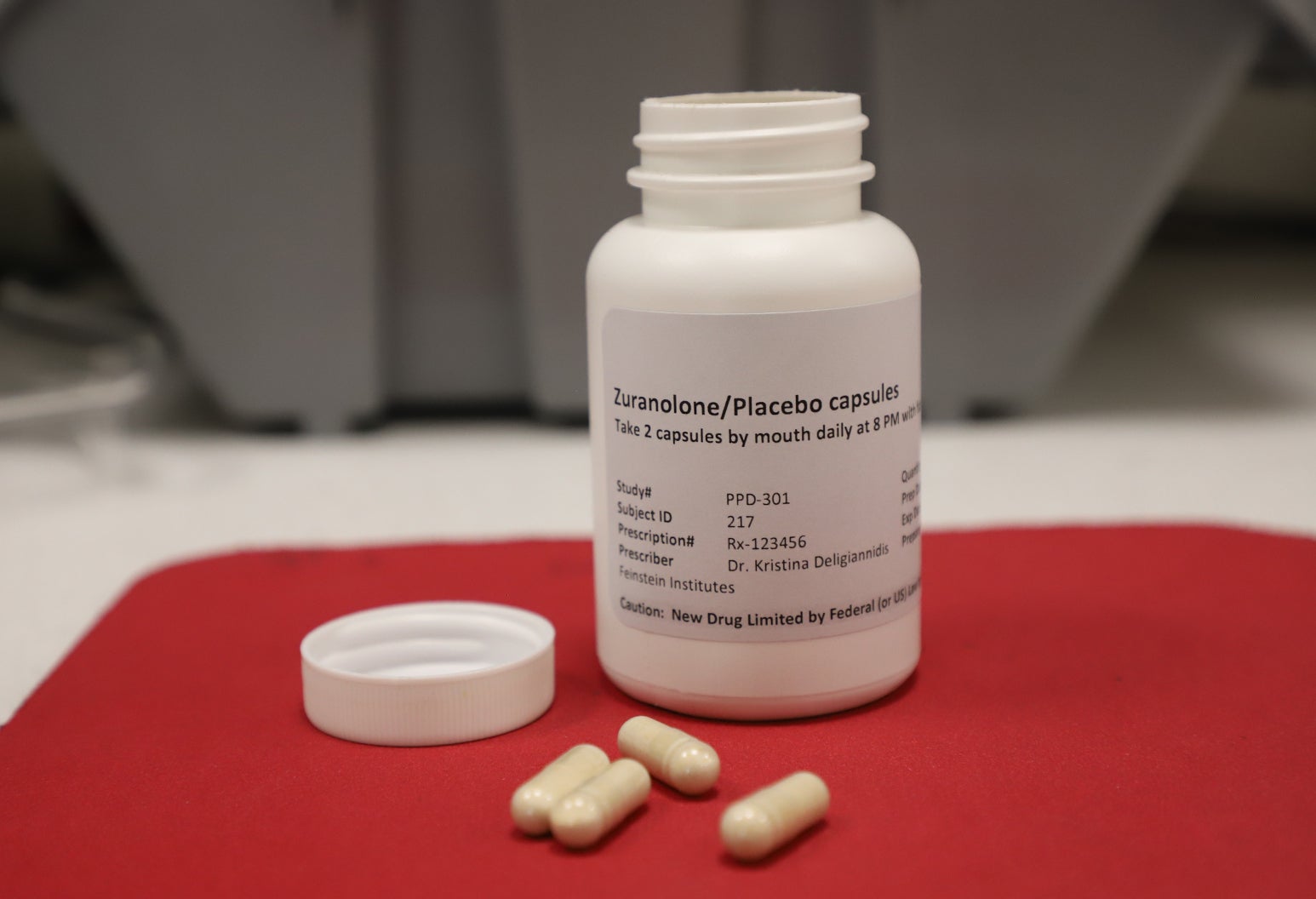

This month, 23 years after Roach experienced those symptoms, the federal Food and Drug Administration announced its approval of the first pill for postpartum depression. The pill aims to provide fast-acting relief to severe symptoms over two weeks.

“It is really revolutionary,” said Roseanne Clark, a clinical psychologist and director of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s postpartum depression research treatment program.

Clarke also joined “The Morning Show” with Roach to discuss advances in care for postpartum depression.

How much the pill could cost patients with or without health insurance remains unclear. Another FDA-approved medication for postpartum depression is an IV injection that requires infusion over 60 hours and an inpatient hospitalization. That treatment typically costs $34,000.

Roach is now a mental health advocate and founder of “Shades of You, Shades of Me,” a national campaign that aims to increase awareness of multicultural maternal mental health.

Roach said accessibility to the new pill will determine its long-term effectiveness. And although the pill could be helpful, she said, other gaps remain in maternal mental health care.

Living in poverty, for example, increases the chances of developing postpartum depression, according to UW-Madison researchers. Symptoms may also be compounded by environmental factors such as childhood trauma, stigma or stress.

“It’s not a miracle drug, but it absolutely can be aided with therapy,” Roach said.

In addition to therapy, universal screening for postpartum depression in health care could ensure more parents get necessary care, Clark said.

Wisconsin’s state health agency estimates 1 in every 5 pregnant people are not screened for depression during prenatal care visits. Four states require maternal mental health screening during prenatal and postpartum visits: California, Illinois, Louisiana and New Jersey.

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide or is in crisis, call or text the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.