Could you get the therapeutic benefits of a psychedelic drug without the mind-bending trip that shakes your world inside out? Would you even want a psychedelic without the hallucinations?

Clinical trials show that psychedelics have tremendous potential for treating depression and other mental illnesses, but there’s still a mystery at the heart of this therapy: Is it the dramatic experience that fundamentally changes a person’s outlook on life? Or the powerful molecules that rewire the brain?

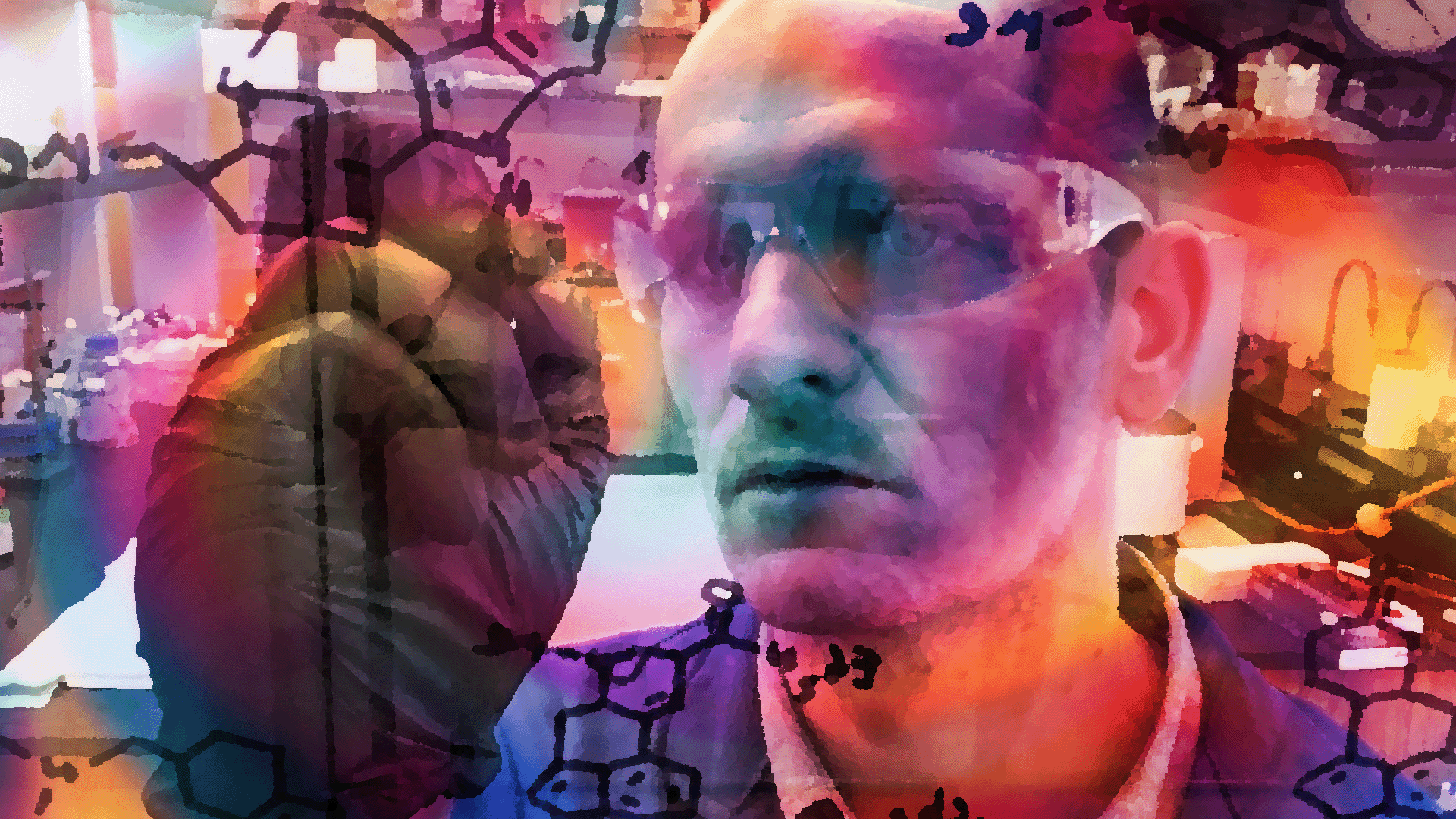

Neuroscientist David Olson believes it’s primarily the chemicals that produce these therapeutic benefits. Now, he’s trying to engineer new kinds of molecules that remove the hallucinogenic trip. Olson calls them “psychoplastogens” — drugs that generate new plasticity in the brain.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Olson directs the University of California-Davis Institute for Psychedelics and Neurotherapeutics. He also co-founded a biotech company, Delix Therapeutics, that has raised well over $100 million for drug development. If successful, his company could change the future of the psychedelic industry.

Steve Paulson talked with Olson for the “Luminous” series on “To The Best Of Our Knowledge.”

This interview transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Steve Paulson: Psychedelic therapy tends to focus on the big hallucinogenic experience. Why are you developing a different model of health care?

David Olson: For some people, that profound subjective experience might be really important for their therapeutic journey, but for others, it may not. The one thing we need to recognize is the scale of the problem. One in five people will suffer from a neuropsychiatric disease at some point in their lifetime. That’s about a billion people worldwide. And as it stands now, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is not very scalable. It needs to be administered in a clinical setting under the supervision of multiple health care providers, which drastically increases the costs and the complexity of the treatment.

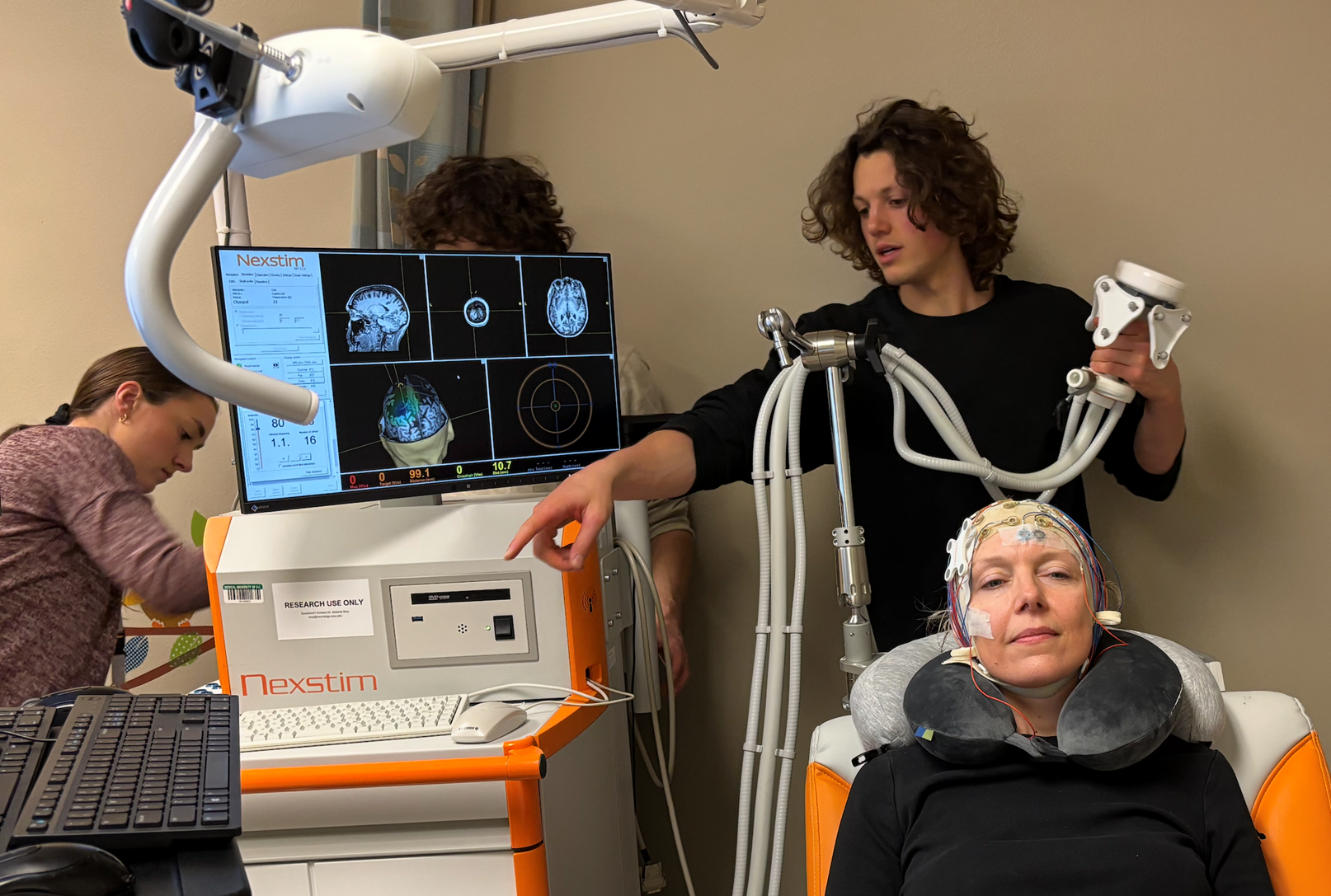

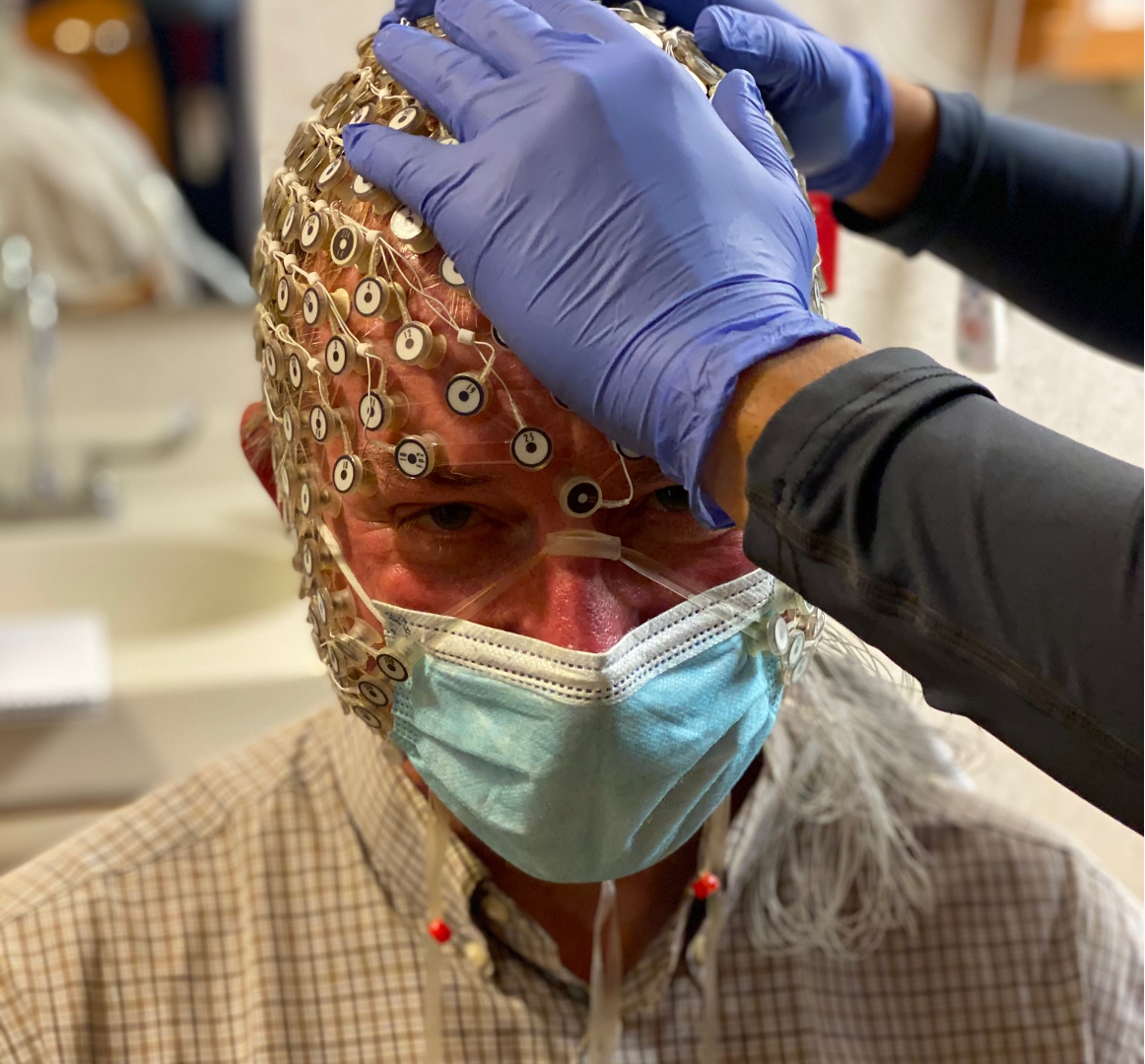

SP: To put this in perspective, two guides typically meet with you, then spend all day in the clinic with you during your psilocybin experience, and then follow up with meetings later. That’s a lot of time, a lot of expense.

DO: It sure is. And some people are not going to have access to that kind of care. They may not live near a psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy clinic. Maybe their insurance won’t cover it. Or they can’t afford to take off the six hours of work for their psilocybin session.

Even in the best-case scenario — let’s assume there is a psychedelic center next to every Starbucks, and every insurance company will fully reimburse it — there are still a lot of patients who will be left out. If you have a condition like schizophrenia or a family history of psychosis or dementia, you may not be a great candidate for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Additionally, there are some cardiac risks associated with various psychedelics. So if you have a heart condition, you may also be excluded.

SP: The common assumption is that the therapeutic benefits come from the mind-bending trip where people see the world in new ways. They have a new sense of meaning and purpose, and maybe they feel connected with the universe. You’re talking about something totally different.

DO: There’s been a lot of great research from people like the late Roland Griffiths, who have demonstrated that a psilocybin experience can be rated by people as being among the most significant experiences in their lives. It’s really hard to convince people who had that type of experience that it might not be related to their therapeutic outcomes, but this is a question that we have to address. For some patients, that type of transformative experience very well could be relevant to their therapeutic recovery. But if there are other patients who don’t need that experience and can benefit by just having physical changes in the structure of their brains, then that would broaden access to a larger number of people.

SP: Why do you think a physical change in the brain with a psychedelic-like substance, but without the hallucinogenic effects, would be effective?

DO: The prefrontal cortex is like a master conductor in the brain, and it talks to all these other brain regions. So cognitive flexibility and control of emotion is mediated by that particular brain region. When you have dysfunction there, a whole host of problems arise. In many brain disorders — ranging from depression to PTSD to substance use disorder and schizophrenia — there is an atrophy of neurons in the prefrontal cortex.

If you think of a neuron like a tree, trees have branches that would be like the dendrites of a neuron. On those branches there are leaves — those would be like synapses in a neuron. In a healthy brain, you have a very rich canopy where you have lots of leaves touching each other so that you have lots of communication between the trees. Squirrels can easily jump from one tree to the next. But in many brain disorders, it looks like wintertime. All the leaves have fallen off, the branches have been pruned back and now there’s not easy access between the trees. And these psychoplastogens seem to rapidly regrow the neuronal arbors and reestablish that synaptic connectivity.

SP: So you are taking classic psychedelic drugs like psilocybin, but somehow stripping out the hallucinogenic effect. Are the molecules similar?

DO: Yeah, structurally that’s been our approach, at least at the start. We wanted to use molecules that had demonstrated clinical efficacy — like psilocybin, like ketamine, like MDMA — and then just make small tweaks to their chemical structures to remove the hallucinogenic effects. So the first generation of non-hallucinogenic psychoplastogens look a lot like classic psychedelics. However, by making systematic changes in the structure of the molecule, you can refine it to the purposes that you’re intending. We can chemically evolve them into something that doesn’t look anything like a psychedelic, but will have similar effects on structural neuroplasticity.

SP: So for the drugs you’re developing, people will just take them at home? They don’t need to see a doctor or a therapist. Then maybe a month later, will they take another pill?

DO: The goal is to create medicines that are safe enough that you can go to the local pharmacy and store them in your medicine cabinet. How frequently you have to take the pill is going to depend on a variety of factors, but they won’t be administered daily. Whether that’s once a week, once a month, once a year, time will tell.

Now, there will be some patients who could benefit from additional interventions like psychotherapy. But you can imagine that these plasticity-promoting molecules that you could take in your home might be more scalable even for that model, because now you can take one of those drugs and interact with a therapist in a virtual environment, over Zoom, that would eliminate the need to go to the clinic.

SP: It seems like a lot is riding on your work. The psychedelic industry is booming, with many startup companies in this multibillion-dollar industry. And if you’re able to deliver the therapeutic effects without having to do the big trip, won’t this take the psychedelic industry in an entirely different direction?

DP: Well, you point to the large dollar figures, but you have to realize that those dollars come from the large number of patients. We’re talking about a billion people worldwide who suffer from some kind of mental illness. So I’m focused on trying to reach the largest patient population that we can.

Now, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is incredible because it’s taking the field in a completely new direction, one that’s more of a healing-based approach than simply mitigating disease symptoms. But if that is the only way to reap the benefit of these molecules, it would be a very, very sad day for this world, because only a subset of very fortunate individuals would be able to access that type of treatment.

But with non-hallucinogenic psychoplastogens, we hopefully can broaden that to the enormous number of people who are impacted by mental health conditions.

SP: Let me ask you about Delix Therapeutics, the company you co-founded that’s doing this research. I believe you have already raised more than $100 million in venture capital, right?

DO: Yes, that’s correct. Delix has been very successful in its fundraising efforts to this point.

SP: What’s your timeline? I realize this is difficult research, but do you have any sense of when you might have drugs coming on the market?

DO: You know, the FDA has a process in place for good reasons. This is going to take years and years of very hard clinical work. It’s incredibly hard to do drug discovery to produce something that is both safe and efficacious that can ultimately get FDA approval.

SP: How many years, if things go well?

DO: Typical drug discovery is a 20-year process. And we’ve been moving pretty quickly. We’re hoping it’s not going to take us 20 years.