Robert has been addicted to heroin since 2011. Before that it was prescription pills, which he took because of back pain. A friend had given him some OxyContin, a prescription painkiller.

“I had it sitting on the table,” recalled the soft-spoken 32-year old Madison man, who requested his real name not be used. “I was cutting it up in pieces, taking a quarter of it at a time and then another friend said, ‘What are you doing?’ He crushed it up and he’s like, ‘Now snort it.’ That’s what started the major opiate addiction.”

Robert said he was taking 80-milligram pills, between 10 and 15 a day. But when drug manufacturers changed the pills so they couldn’t be crushed, Robert turned to heroin.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

He said he’s overdosed several times, losing consciousness and coming to, gasping for air.

“I woke up at the last minute three times now. It was just foggy, I didn’t know what was going on,” he said. “Afterwards, it’s kind of scary. That’s when (the possibility of death) hits you.”

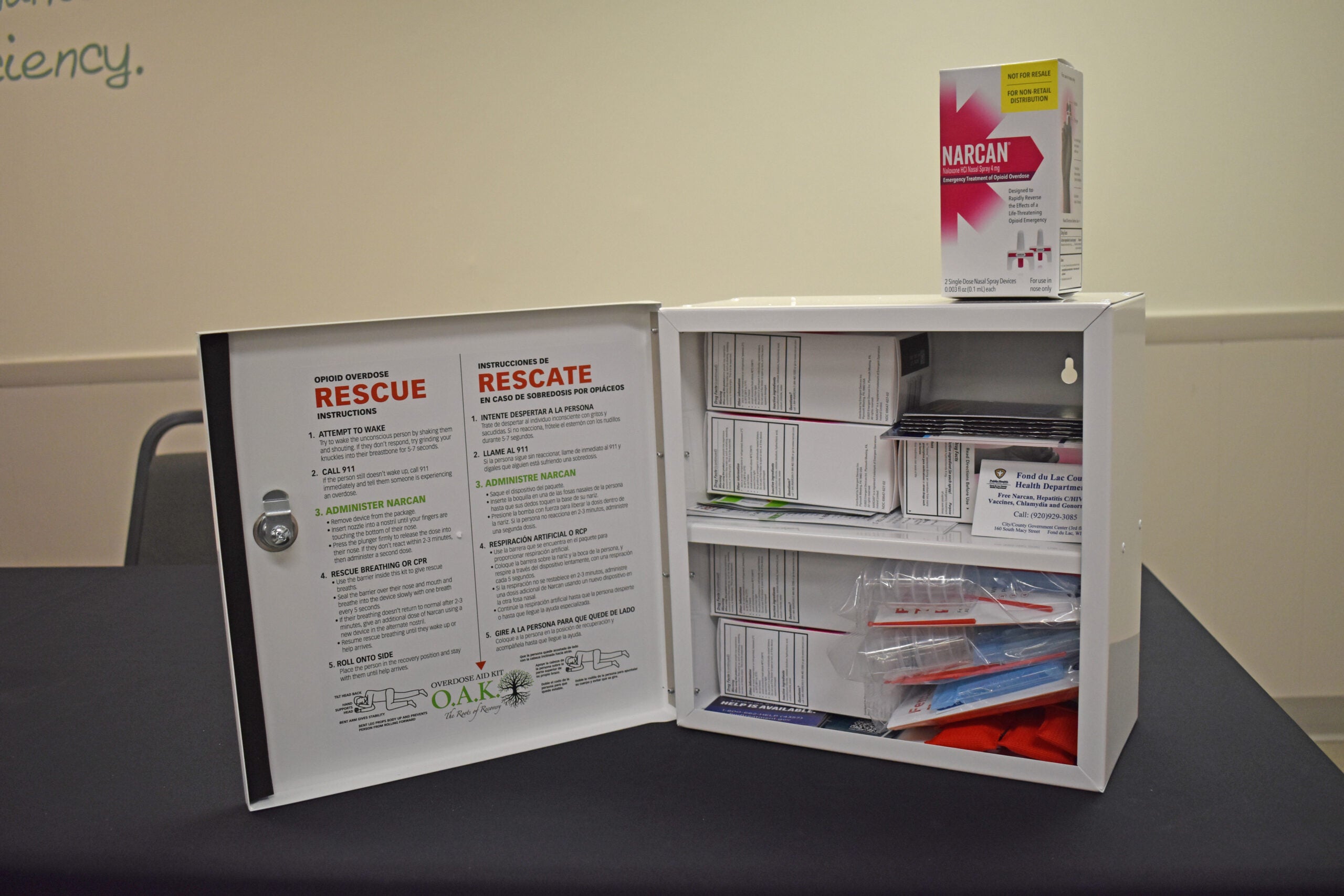

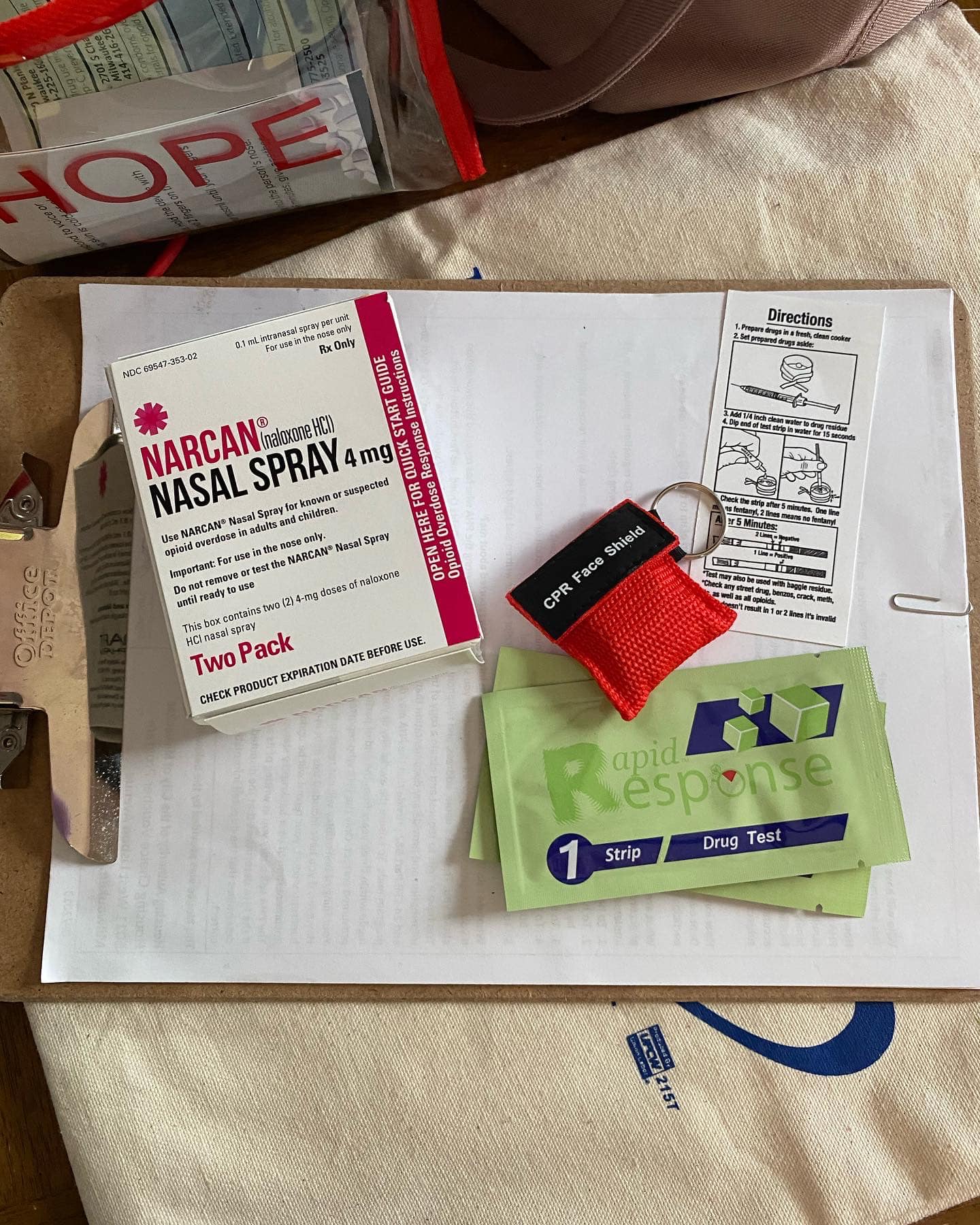

To head off close calls like that in the future, Robert’s mother (also not named here to preserve privacy) has learned how to use naloxone, the antidote for those who overdose on opioids. She recently went to a training session put on by the AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin, where addicts’ parents learned how to administer the medication.

While similar educations programs along with law enforcement policy changes have made it more likely that family members and first responders will be ready with naloxone in an overdose situation, challenges remain.

The AIDS Resource Center’ prevention specialist Heidi Olson-Streed warned parents that even after they’ve administered the medication, their work isn’t done.

“Addicts can be pretty sneaky sometimes and they’ll be like, ‘Uh-oh, I really gotta go to the bathroom, I feel like barfing.’ You definitely don’t want them doing anything else on top of what they just did and what you just reversed. So don’t let them out of your sight.”

Madison Police Chief Mike Koval, who also attended the training session, said it’s not unusual for someone to overdose more than once. He told parents it can be frustrating for his officers who carry naloxone. Some have mixed feelings about repeatedly reviving addicts who are likely to overdose again. Koval said every life is sacred and he read from a letter sent by parents whose daughter was revived by a police sergeant:

“Our oldest has long struggled with addictions and will continue to do so. But she is alive today for that struggle because of the compassionate work of your officers. Our daughter may not now or ever truly appreciate the chance that she was given that morning, but we do. We do deeply.”

The lure of heroin is so strong that many try to quit, only to use again. Robert said he can’t count how many times he’s tried to quit. He’s in outpatient treatment now. Prior to that, the longest he’d been clean was nine months. He didn’t intend to end up an addict.

“My parents made sure me and my brother had everything we needed,” he said. “We went to a Lutheran school growing up, lived in a good neighborhood, went on camping vacations. I had every opportunity to succeed and do well.”

Drugs, he said, don’t discriminate: No matter what walk of life you’re from or how much money you have, where you live, they’ll get you if you let them.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.