Lawmakers heard more than nine hours of heated testimony Tuesday as Republican members of a joint rules committee prepare to temporarily undo updates to Wisconsin’s vaccine requirements for children entering schools and day cares.

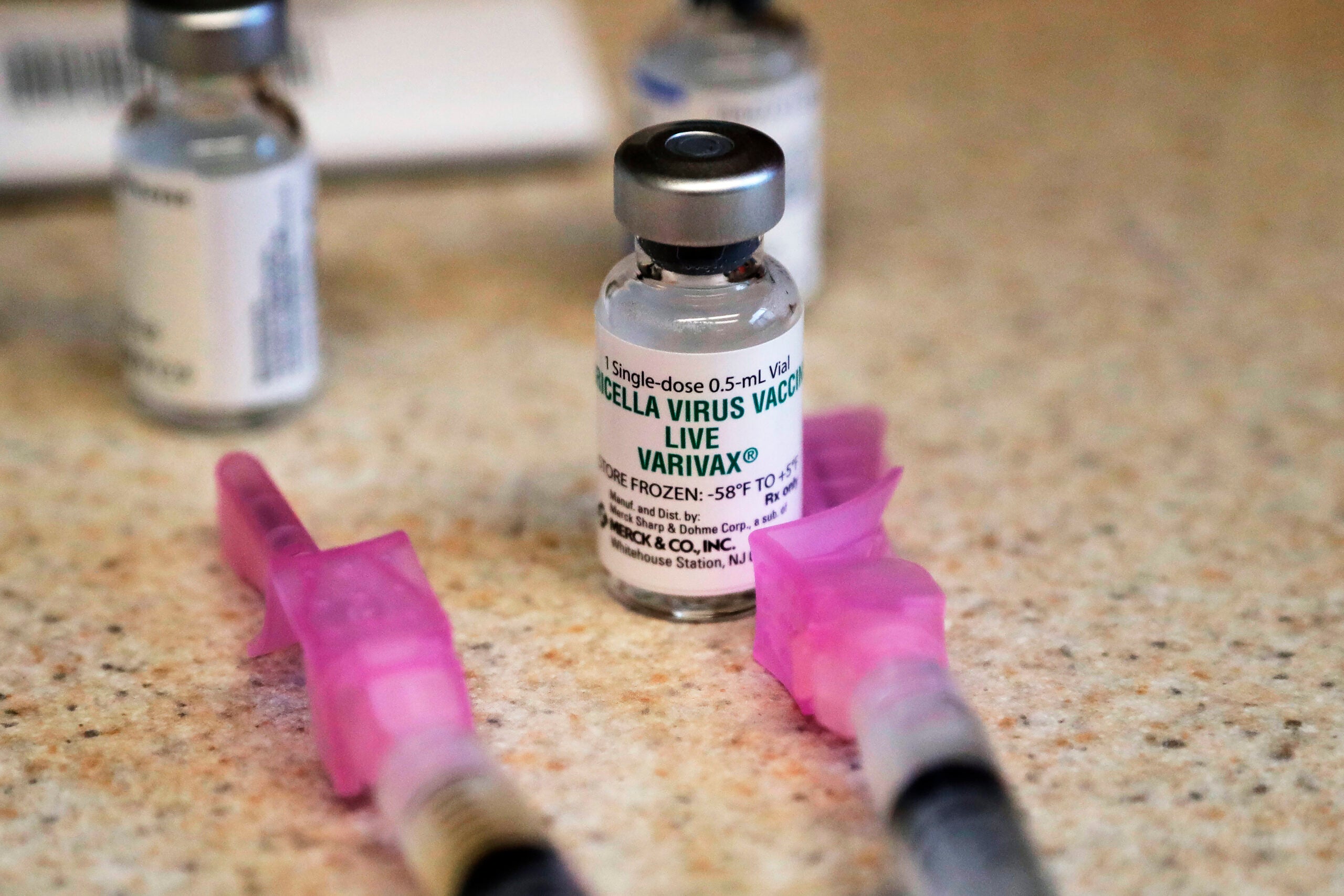

The updates introduced by Wisconsin’s Department of Health Services include adding meningitis vaccines to the list of immunizations required for students. The changes also require parents to get a medical provider’s sign-off if they want to cite prior infection as a reason for skipping the chickenpox vaccine. Previously, parents could simply attest to the fact that their child has had chickenpox.

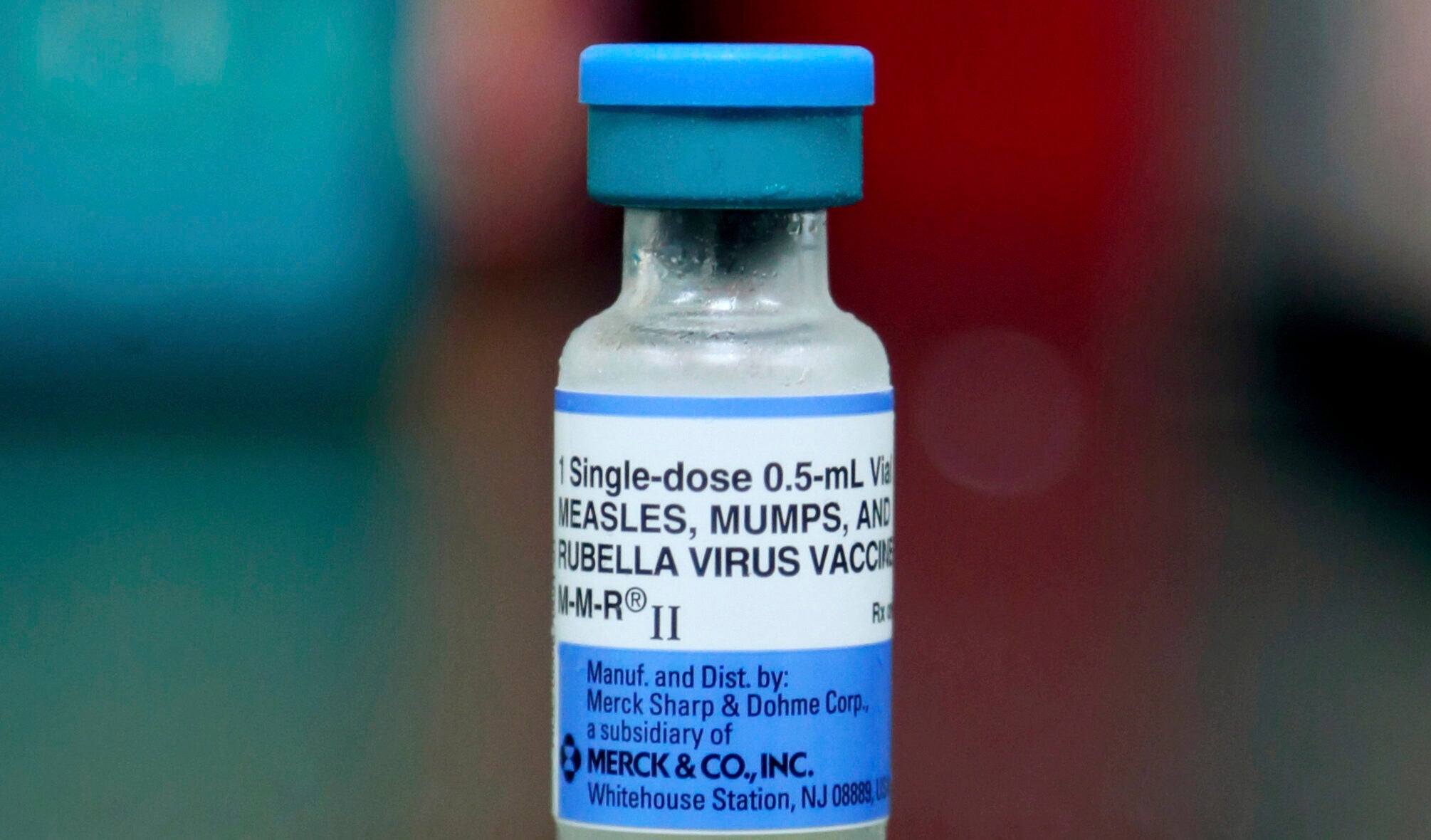

Additionally, the DHS changes add statewide criteria for identifying a “substantial outbreak” of chickenpox or meningitis, and changed the threshold for a substantial mumps outbreak from at least 2 percent of the unvaccinated population to at least three connected cases.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Some Republicans characterized those outbreak definitions as overly strict, and expressed concerns they would be used to keep children from in-person schooling.

“I do believe that there are some issues within this rule that do pose some undue hardships on parents,” said state Rep. Adam Neylon, R-Pewaukee, who co-chairs the Joint Committee on Administrative Rules.

The committee will soon vote on suspending portions of the DHS rules, said Sen. Steve Nass, R-Whitewater, the panel’s other co-chair.

In 2020, the committee voted to block similar vaccine rules, which were also introduced by the DHS, an agency run by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers’ administration. A bill that would have made the suspension permanent died without becoming law.

Wisconsin parents may still get waivers exempting their children from any of the state’s required vaccines by citing medical, religious or philosophical objections. The rules update proposed by the DHS would not have changed that exemption, which is written into state law.

The health department’s changes took effect Feb. 1 for day cares, and they’re currently scheduled to take effect next school year for school settings.

Health officials added the requirement for that a medical provider must attest to a child’s chickenpox history because parents aren’t always accurate in recognizing the disease, said Stephanie Schauer, who oversees Wisconsin’s immunization program. That’s especially true now that the introduction of the chickenpox vaccine in 1995 has changed the disease from commonplace to rare, Schauer said.

“We’d like to make sure that every child who we think is immune truly is,” she said.

That diagnosis of chickenpox wouldn’t need to happen in person, Schauer said. Instead, it could come from a telehealth appointment, or it could be done after the fact based on a blood test or a description of symptoms.

The health department’s changes would also shift a requirement for getting the vaccine that protects against tetanus, diphtheria and whooping cough from students entering sixth grade to students entering seventh grade. Officials said that timeline would better align with national recommendations that children get that vaccine by age 11 or 12.

Many of those testifying Tuesday repeated vaccine misinformation, including the debunked belief that vaccines cause autism. The testimony also delved into COVID-19, including discussions of the drug ivermectin and Wisconsin’s handling of the pandemic.

Nass drew applause from the crowd when he derided Wisconsin’s Chief Medical Officer, Dr. Ryan Westergaard, as “Wisconsin’s Dr. Faucci.” Nass questioned how the public could trust recommendations from Westergaard and other health officials in the wake of COVID-19-related shutdowns.

“When I look back, there was that urging of everybody to ‘mask up, shut down, don’t go anywhere,’ and my gut was telling me, this is not right,” Nass said of the pandemic.

The American Academy of Pediatrics “strongly” urges children to get vaccines according to the recommended schedule, and Dr. Jennifer Kleven of the AAP’s Michigan chapter testified in support of the DHS updates.

“Seeing children ill with diseases that could be prevented with vaccines is devastating to providers and devastating to families,” she said. “Our most vulnerable children — in particular, those who can’t receive vaccines due to illnesses such as cancer — and infants too young for vaccines are at the highest risk for the most devastating consequences.”

Last school year, 88.7 percent of Wisconsin students met minimum immunization requirements, a 3.2 percent decrease from the previous year, according to data collected by the state.

The health department’s list of required vaccines for students does not include the COVID-19 vaccine or the seasonal flu shot.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.