The world’s top rock climbers are a special breed. It’s not just their fearlessness, dangling off cliffs that soar thousands of feet straight up. It’s also their technical prowess. The best climbers can find a toehold in the tiniest hole on a rock wall, sometimes no bigger than the edge of a credit card. They can pull themselves up by a single finger. Tommy Caldwell is perhaps the best big wall climber of them all.

In 2015, he and Kevin Jorgeson completed the hardest climb in history — the 3,000-foot Dawn Wall on Yosemite’s iconic El Capitan rock formation. It took 19 days and capped seven years of Caldwell’s intense planning and training.

While this was his greatest climbing achievement, it wasn’t his most difficult ordeal. In his early twenties, he was kidnapped by Islamic militants while climbing in Kyrgyzstan. “I definitely thought I was going to die,” Caldwell said. He only managed to survive by pulling his captor off a cliff.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Caldwell chronicles his life of adventure in his memoir, “The Push: A Climber’s Journey of Endurance, Risk and Going Beyond Limits.”

This interview has been edited from its original version for clarity and length.

Steve Paulson: When did you start climbing?

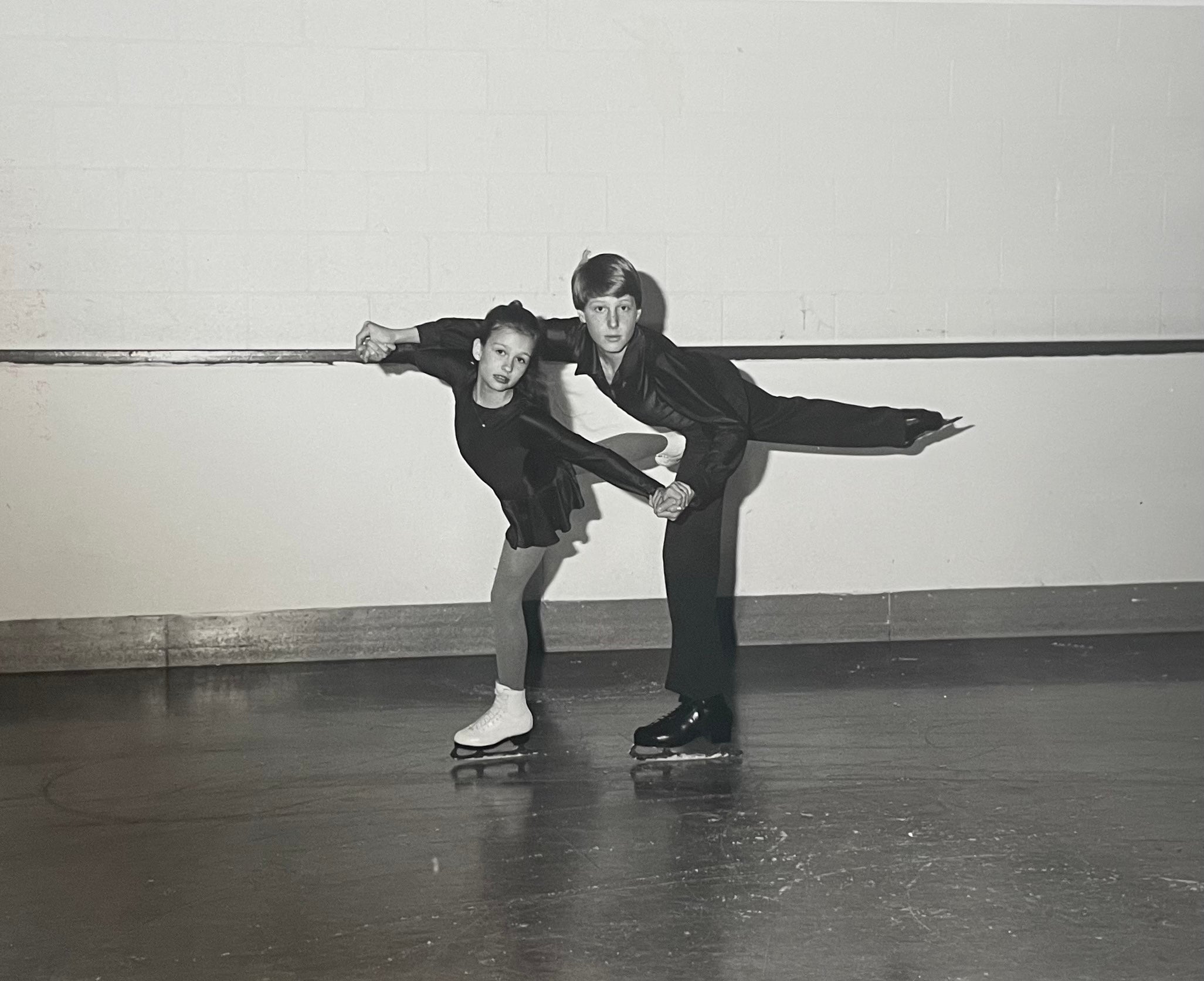

Tommy Caldwell: I started climbing when I was three years old. My dad was actually a mountain guide. So it’s kind of what we did growing up.

The first climb my parents like to talk about me doing was a thing called the Bowels of the Owls on this rock spire called Twin Owls, which is a few hundred feet tall. And it just progressively got bigger and bigger.

I started going to Yosemite every year. We also did a lot of ski touring. It was a very abnormal way to grow up. I think everybody looked at my dad thinking he was a bit of a lunatic — bringing me and my sister out on these very scary-looking adventures.

In a way, I spent my life out on the battlefield. He changed my diapers in snow caves. I knew how to crouch in the right way to avoid lightning strikes when I was seven years old. So it changed my view on risk, which could have gotten me in trouble.

SP: By the time you were in your early 20s, you were one of the world’s top climbers. You and your girlfriend and two other guys went to Kyrgyzstan, where you were kidnapped by Islamic militants. They held you hostage for six days as you were getting chased around by local army soldiers. Did you think you were going to die?

TC: I definitely thought I was going to die. We were held hostage for six days in the middle of this war. We had to abandon all of our food, all of our warm clothing. We were on the verge of hypothermia because we were high in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan, probably 50 miles from the nearest road.

We were climbing up this big 2,000-foot mountain with our one remaining captor. By this time the other captors had been picked off by the Kyrgyz military. High on the mountain, I’d made the decision to take matters into our own hands. So I ran up behind this armed rebel, grabbed his gun strap and pulled him over this ledge. And he fell out of sight. Then we ran down the valley to the nearest military outpost. That’s how we escaped.

SP: How did you feel about pushing him over the cliff?

TC: I felt really mixed. A lot of people were like, “Oh, you did such a heroic thing by pushing this evil man off the cliff.” But to us he wasn’t evil. He was a victim of circumstance, a 19-year-old hired mercenary. And it was really hard for me. Who am I to take somebody else’s life? Was I an evil person?

Over time, however, I did sort of understand and even learn to appreciate what that did for me psychologically and how it helped me grow into a man. It was actually quite empowering because I knew that when things really go badly, I had the capacity to respond. I felt almost invincible and it was the survival instinct kicking in.

SP: You are most famous for your climb of the Dawn Wall on Yosemite’s El Capitan. It’s considered the most difficult big wall climb in the world. What makes this climb so hard?

TC: It looks impossible. Most of the other routes on those big walls have crack systems, and to a trained eye you can imagine climbing them. But even to me, the Dawn Wall looks blank. It looks like there’s no way to climb it. But after having climbed on El Cap for 15 years, I understood that little holes form that you can only see if you get your face a few inches from the wall. If you train yourself properly and you’ve had a lifetime of practice, you can learn to climb on them.

It’s really like a dance or a gymnastics routine to successfully climb this stuff. You have to rehearse the moves over and over and over again until you can do the routine perfectly.

And trying to link together this maze of climbing moves up a 3,000 foot wall is just a fascinating question. So that was a seven-year process — first, finding the route up the wall. You know, this project was about picking a goal that is above you and then trying to change your life in a way that you can rise to that level.

SP: You were on the Dawn Wall for 19 days. So when you and your climbing partner, Kevin Jorgeson, finally reached the top — which you’d obsessed about for a decade — did it feel like you’d gotten the monkey off your back?

TC: It was something that I doubted for so many years and then it actually worked out. This magical journey, it was so unbelievably beautiful to me. And ending it was like a love affair being done. It was a weird mixture of relief and sadness.