When the first coronavirus vaccine received emergency use authorization in early December, the advice for pregnant and breastfeeding women was: You may choose to get vaccinated. Your medical professional can help you make a decision.

Clinical trials for the two coronavirus vaccines authorized by the Food and Drug Administration demonstrated the vaccines are effective for most adults ages 16 years and older (Pfizer), and 18 years and older (Moderna). Doses for those groups are already being administered around Wisconsin.

But experts caution that because the vaccines were developed so rapidly, there hasn’t yet been time to answer all the questions public health experts — and the public in general — have about the vaccines.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

For example: there’s not yet enough evidence to determine whether someone who receives a coronavirus vaccine can still spread the virus to someone else, and health care providers are encouraging everyone to continue basic precautions like wearing masks, social distancing and hand washing.

Other questions that don’t have enough data yet are how safe and effective the vaccines are for pregnant and breastfeeding women, and children. Dr. William Hartman of UW Health said the dearth of data doesn’t mean researchers think the vaccines are unsafe for those groups.

Hartman is the principal investigator for the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial at UW Health and answered a series of questions about what we do and don’t know about the vaccine in these groups.

Pregnant Women

None of the clinical trials for coronavirus vaccines so far have allowed pregnant women to participate. That’s pretty common for clinical trials — researchers find it easier to not have to consider the health of both a pregnant woman and her fetus in their trials.

As a result, Hartman said, “We currently have zero data looking at the COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant women.”

Nevertheless, the FDA’s emergency authorization of the vaccines does not exclude pregnant women, leaving the door open for them to get vaccinated. Hartman said some pregnant women in groups that are recommended to get the vaccine — like health care workers — may decide to get the shots.

Hartman said pregnant women should consider their personal context with their doctor and loved ones: “Are you in a risky job? Is the risk of having the virus greater than the potential risk of getting the vaccine?”

There is plenty of precedent, he noted, of pregnant women receiving vaccines safely, like the flu shot.

Breastfeeding And Lactating Women

Like pregnant women, breastfeeding women were also excluded from the vaccine trials, a decision that’s drawn ire from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. But also like pregnant women, breastfeeding women who are in the groups currently recommended to get vaccinated may opt to do so.

The CDC notes that with the exception of the smallpox and yellow fever vaccines, “neither inactivated nor live-virus vaccines administered to a lactating woman affect the safety of breastfeeding for women or their infants.”

Conventional vaccines fall into those “inactivated” and “live-virus” categories, meaning they rely on a weakened or killed version of a germ to trigger an immune response in the body.

The vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna use an entirely different technology called mRNA that doesn’t contain the virus at all.

“It’s like passing a note into the cell that the cell can produce a protein,” Hartman explained. “And that protein then goes to the cell surface so an antibody can be generated.”

mRNA are not thought to pose a risk to the breastfeeding infants whose mothers get the shots. In fact, Hartman said the antibodies generated by the vaccine should be able to get into a mother’s breast milk, potentially passing on immunity to an infant.

Hartman said he’s aware of at least one study that is looking at the COVID-19 antibody levels in breastmilk so more will likely be known on the topic soon.

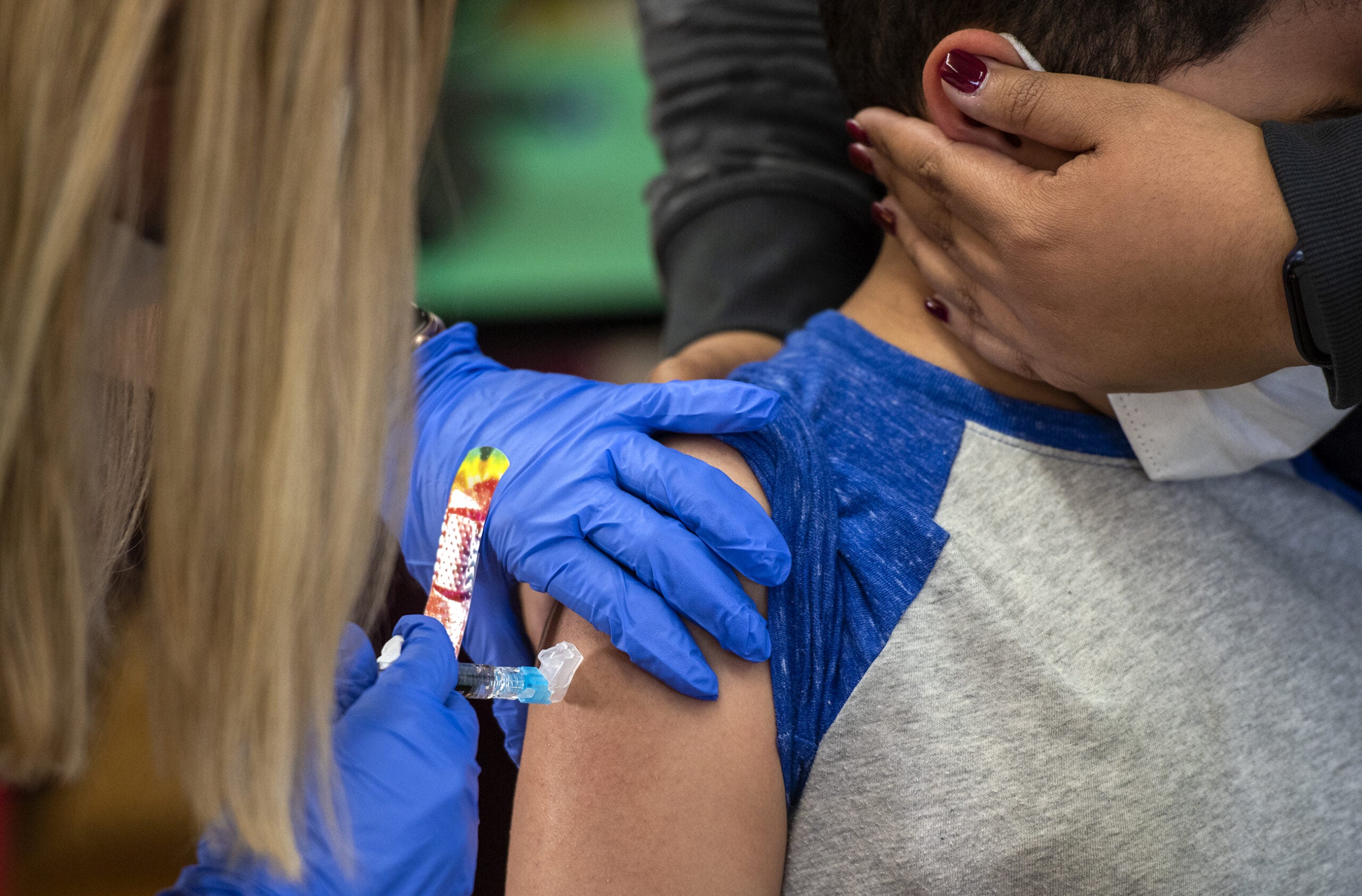

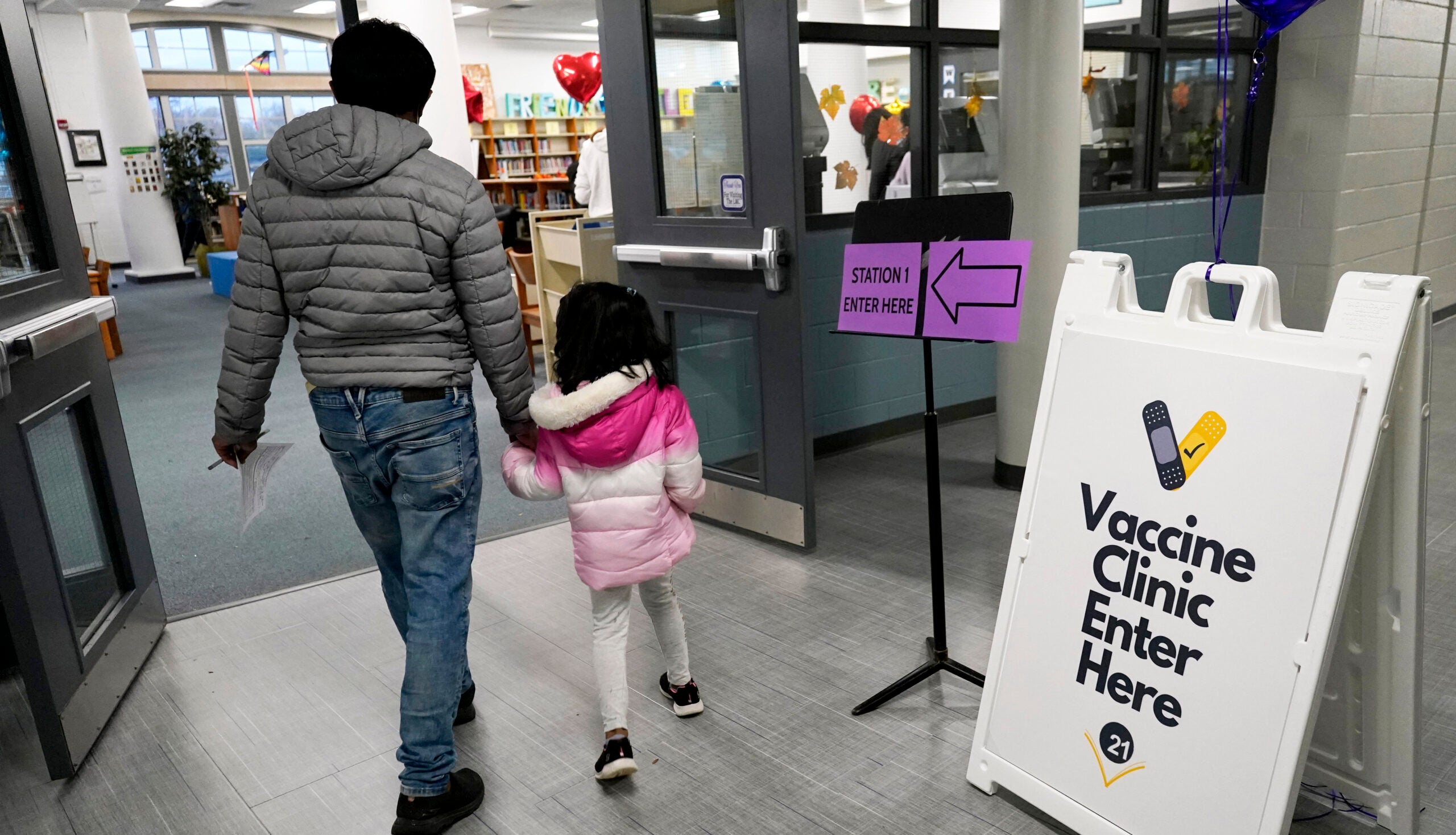

Children

When it comes to children, Hartman said researchers need to make sure the vaccines are safe for those under 18 years old before they’re recommended for that age group. That’s because children sometimes react differently to vaccines than adults do, he said.

“Kids can have different reactions to different vaccines. And sometimes their reactions can be more severe than what adults develop,” Hartman said. “And so we just have to make sure that the profile looks good, that it looks safe, so that children can get (the vaccines).”

The good news, Hartman said, is that the answer to these questions may be just around the corner.

Hartman said the reason children have been lower on the priority list for studies is because they tend to get less sick from the coronavirus.

“And so the priority has been on adults, and especially, especially elderly adults, when these vaccines have been established,” Hartman said.

But with studies on pregnant women and young children likely to begin in January, it’s possible more will be known by the time vaccines are widely available to the public.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.