At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, many health experts were concerned about the new disease’s impact on older adults and people who are immunocompromised.

Jenna Nobles, sociology professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was interested in another potentially vulnerable group – pregnant people.

“We know that emerging infectious diseases can be extremely consequential for pregnancies, both people who are carrying the pregnancies and the infants who are born from them,” Nobles said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Now, more than three years later, Nobles and her research partner Florencia Torche from Stanford University have published a study that identifies a spike in premature births caused by COVID-19.

They found that from 2020 into 2023, maternal COVID infection increased the risk of preterm births by 1.2 percentage points. The rate was especially high during the second half of 2020, coming in 5.4 percentage points higher than anticipated.

“A one percentage point jump is already very large,” Nobles said. “To move the needle that much on population risk is akin to exposing pregnant people to weeks of very high levels of environmental exposure, air pollution from wildfire for example.”

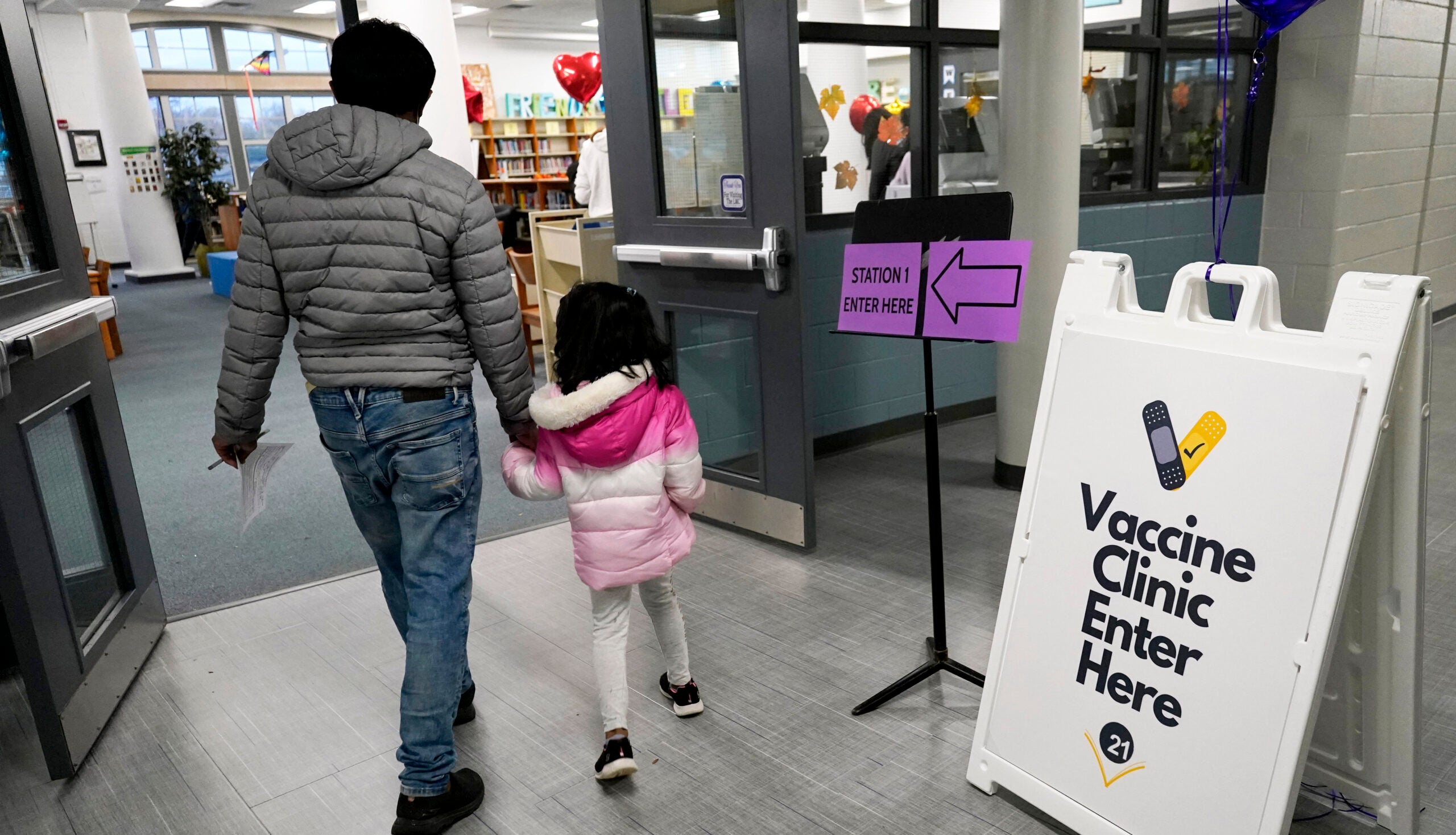

The study also found that the premature birth rate returned to normal levels after the roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccine. Nobles said the decline in early births happened earlier in communities that had early adoption of the vaccines by residents.

“That becomes a really important piece of information to have,” she said. “It’s not just that vaccines are safe and effective in pregnancy. It’s also that avoiding vaccines can be very harmful, particularly in the context of emerging infections like COVID.”

She said the research could help people who are pregnant now and considering getting the vaccine for the first time or even the latest booster.

Nobles’ research used data from 40 million people provided by the California Department of Public Health, which recorded COVID-19 test results for people in a hospital to give birth during the three-year period. She said the state agency was also able to provide information about those peoples’ previous births, allowing the researchers to understand a person’s risk for premature birth prior to the pandemic and more definitively link the increase to COVID-19.

“That’s a really important part of this study design,” Nobles said. “A challenge is that who gets COVID is not random in populations and certainly early in the pandemic, people were differentially exposed who had frontline jobs and who lived in more crowded settings.”

While the research offers a look back on how COVID-19 impacted pregnancies during the height of the pandemic, Nobles said she hopes the study will also inform how healthcare providers and officials are thinking about what data should be collected during a future epidemic or pandemic.

“Data like vital statistics records that are partnered with information about infectious disease and vaccine uptake, they can be a very important tool to study how the effects of epidemics are evolving in real time,” she said.

She said maternal and infant health outcomes should be among the metrics that leaders consider as they develop a public health response to future infectious disease.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.