The United States surgeon general was in Madison where he gave a frank talk about what works — and doesn’t work — regarding public health.

“We need to realize as health advocates that what we’re selling, people aren’t buying. And we have to reframe and repackage what we’re selling in a way that people will buy it,” U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Jerome Adams told local health officials during a forum Thursday organized by SSM Health and UW Health at the Edgewater Hotel.

While state health commissioner in Indiana, Adams convinced then-Gov. Mike Pence to allow syringe exchanges to deal with an HIV outbreak in a rural county.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

As a physician, Adams said he knew what to do, but he had to convince others.

“Our struggle was trying to engage our community and get buy in what for them — and a lot of our country — was a very controversial intervention,” he said.

Part of the persuasion involved meeting with the local sheriff, the local pastor and the head of the local chamber of commerce.

“And by going to that community and showing that we cared about them, suddenly they cared what we knew,” Adams said. “We were able to get them to be advocates and institute a syringe service program and, I’m proud to say, halt the spread of HIV in that community.”

That’s when Adams had a eureka moment.

“I always intuitively knew and felt that, but after that happened, the whole idea of better health through better partnerships came to me,” he said.

One of the surgeon general’s initiatives is Community Health and Economic Prosperity, CHEP, which aims for employers and the private sector to be involved in public health.

“Businesses that invest in their community’s health will see economic dividends and economic returns. This is more than just worksite wellness programs,” he said.

Not only is the country less prosperous if workers aren’t healthy, he said, but the U.S. is also less safe.

“Seventy percent of our 18- to 24-year-olds are ineligible for military service — 7 out of 10,” Adams said. “So that means that our country is not just looking to increasing rates of hypertension and cardiovascular disease and stroke and cancer 20 years down the road because of our obesity, smoking and inactivity, we are literally a less safe country right now because we’re an unhealthy country.”

One of the biggest health crises is the opioid epidemic.

In visiting communities across the U.S., Adams said there’s a lot of despair but also a lot of hope.

Damond Boatwright, left, SSM Health president of operations, listens as U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Jerome Adams talk about the intersection of health and the economy in Madison. Shamane Mills/WPR

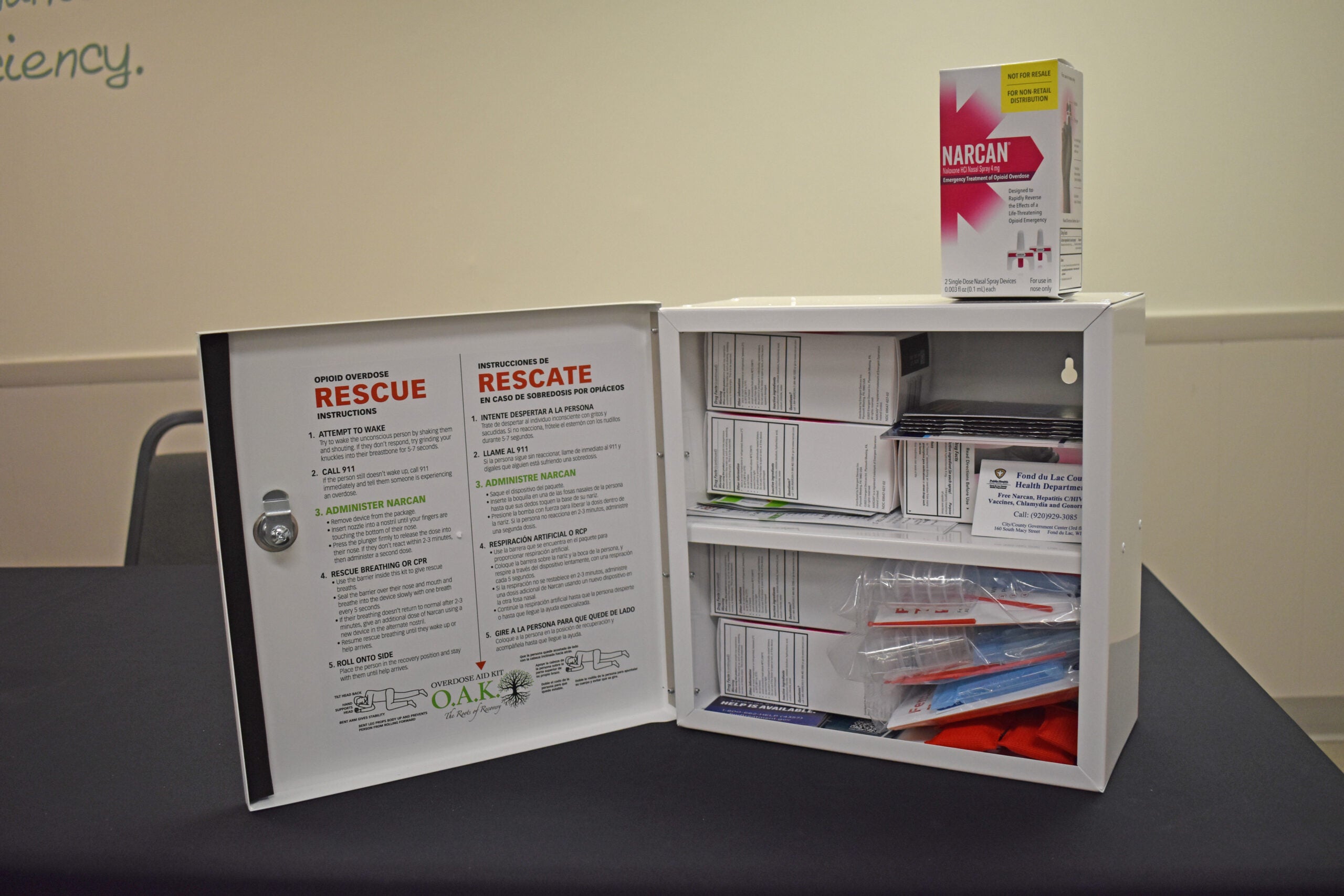

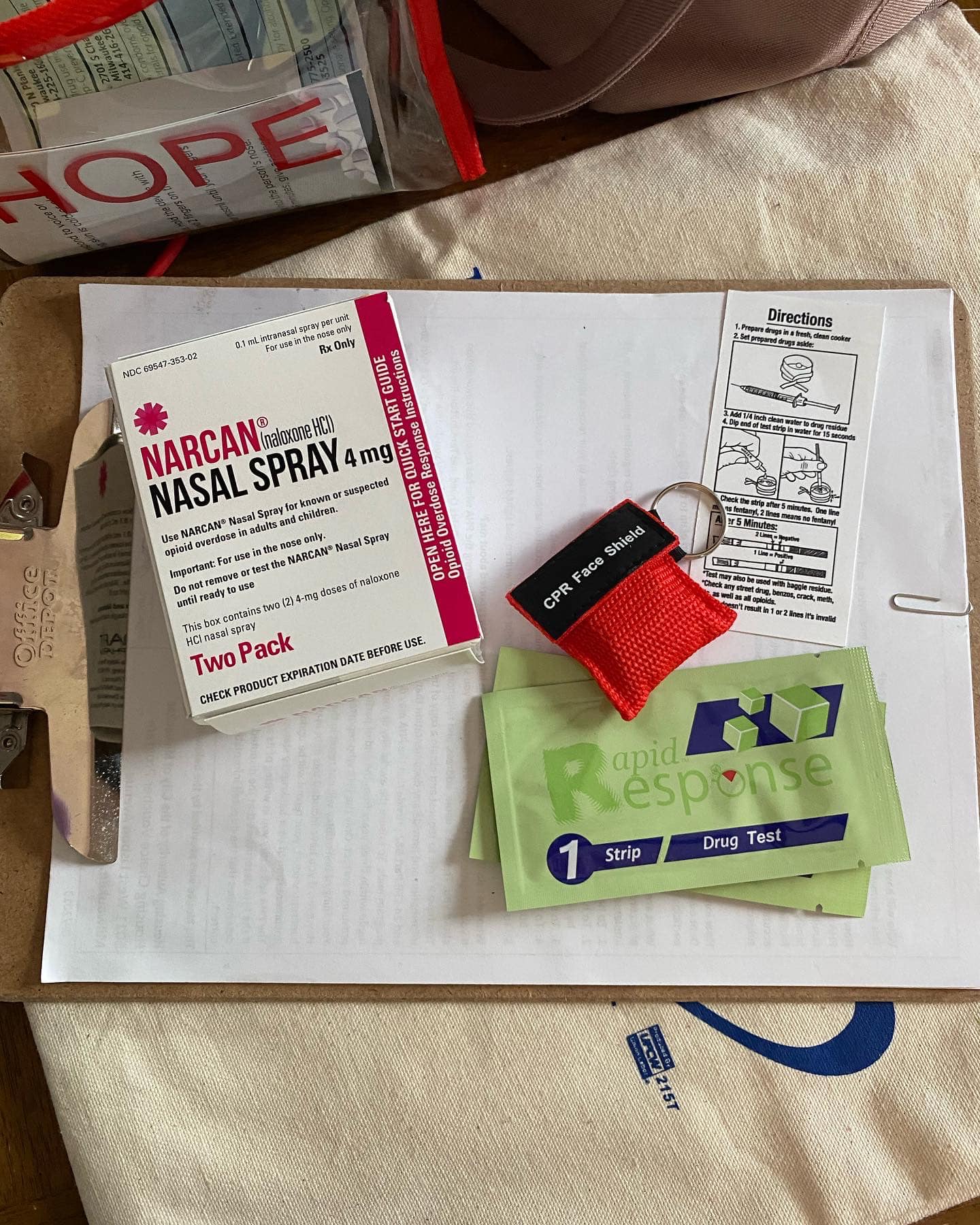

The communities that have reduced overdoses, he said, have saturated the community with naloxone. In 2016, Gov. Scott Walker signed a standing order allowing people to get naloxone, an overdose reversal drug, without a prescription.

Local officials also put out a video advising how those in the community could spot an overdose and help.

Overdoses have skyrocketed over the years.

There were 883 fatal opioid overdoses in 2017, according to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

This spring, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that suspected opioid overdoses had risen dramatically from July 2016 through September 2017. In Wisconsin they more than doubled.

Adams also said getting addicts into treatment right after an overdose is key.

“The unfortunate part is that the best place for a drug dealer to hang out is either in the jail parking lot or the ER parking lot,” he said.

But he cautioned that some of the efforts to curb opioid abuse may backfire.

“Too many folks around the country are patting themselves on the back for their plummeting prescribing rates, but 62 percent of people who inject drugs say that they either got started or continue doing drugs because of chronic pain,” Adams said.

The nation’s doctors, Adams said, can’t decrease how many opioids they give patients without making sure there are alternatives to help those in pain.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.