A majority of Americans run into health misinformation while scrolling on social media or shopping online. And, most aren’t able to differentiate fact from fiction, according to a poll by KFF.

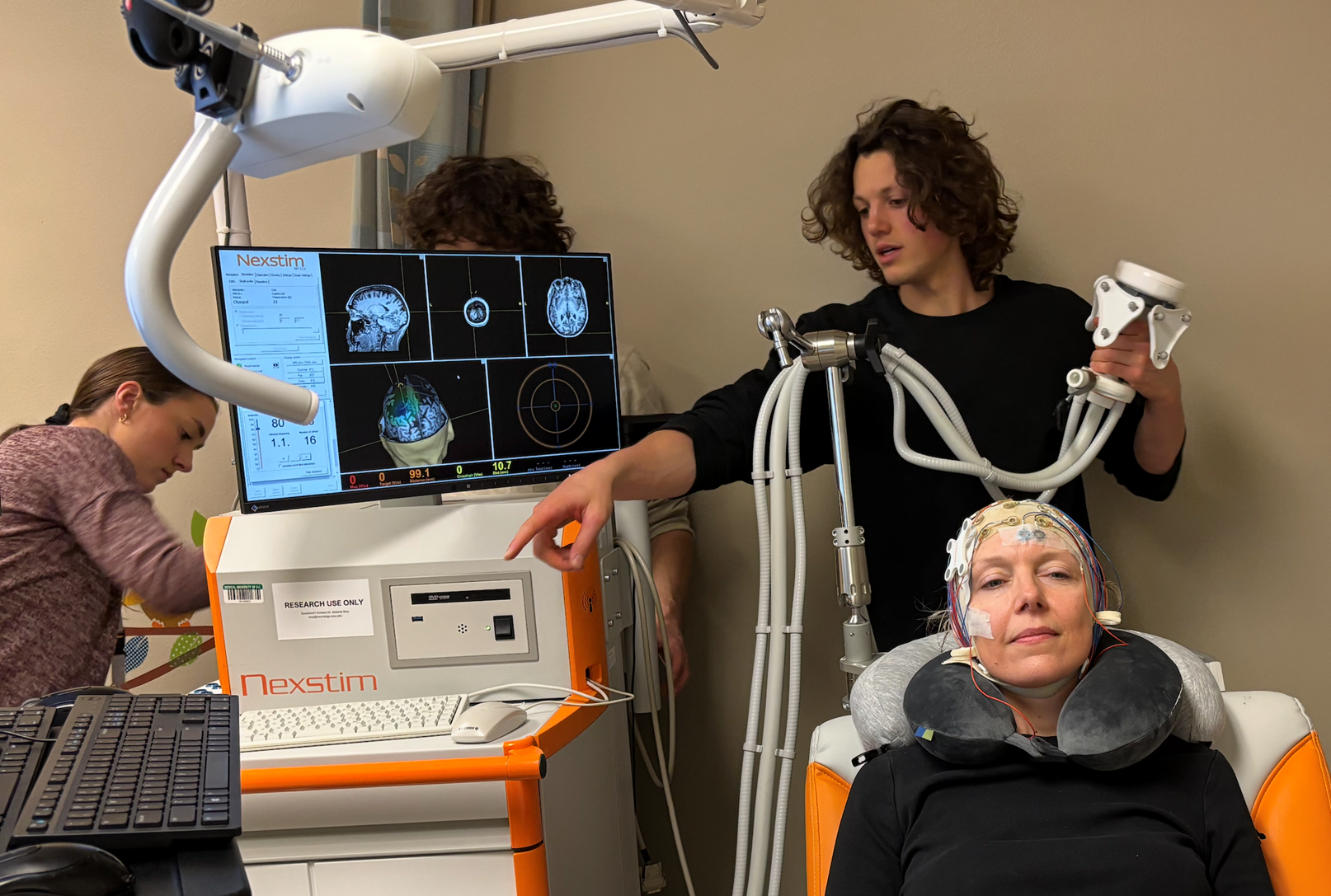

UW Health’s Sarah Kotila is working to clear things up for cancer patients and their families. She’s a nurse and the clinical trials navigator manager at the Carbone Cancer Center.

Kotila said there is a fair amount of misinformation around clinical trials for cancer care.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I think some of them have stemmed from things that have happened historically and things that we need to acknowledge probably weren’t done in the most ethical manner,” Kotila said. “But today, we have a number of checks and balances for patients that are going to go on clinical trials.”

Kotila joined WPR’s “The Larry Meiller Show” to talk about misinformation, clinical trials for cancer and the effort to rebuild patients’ trust.

The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

LM: How can misinformation about cancer affect people’s decisions about their health?

Sarah Kotila: It can have disastrous effects. Unfortunately, a great recent example of that is the COVID pandemic. A lot of people were scared to get the vaccination, and COVID was affecting a lot of minority populations more than it was affecting others.

The history of mistrust in the medical community really played a part in some of the misinformation that was out there, and the misbeliefs.

I think we need to acknowledge that, and do a better job of trying to help people understand how clinical research has evolved. We need to educate about what the checks and balances are, that a clinical trial is voluntary in nature, and that a patient always has a choice of whether they want to participate in something.

LM: How do you help your patients decide whether to participate in a clinical trial?

SK: I tell patients and providers that clinical trials are another treatment option that patients can always consider. Any time a patient needs a new treatment, there’s always the standard that’s been used to treat a certain type of cancer. There may also be clinical trials out there looking at new ways to treat cancer.

Clinical trials are always optional. That’s something for patients to keep in mind. No one can ever force you to go on a clinical trial or make you participate. It’s an option to consider, and sometimes clinical trials can give patients more options for treatment.

LM: I had a friend who went through a clinical trial at UW about eight years ago. He had fourth stage pancreas cancer. His thought was that the trial might not help him, but maybe somebody else down the road.

SK: I think participating in a clinical trial is really a personal choice. Of course, most people want a treatment that’s going to help them. But I do think that some people want to contribute to science and to help those that come after them.

I think another important topic to touch on is that there are a lot of myths out there. People think that clinical trials are only a last resort, and that’s not true. There can be clinical trials at any stage of cancer treatment, and it can be for early or late stage cancer.

I always encourage patients and their providers to take a pause and look anytime there’s a fork in the road of a patient’s treatment or a new diagnosis, to see what all the options are out there.

LM: What are some more examples of misinformation around cancer and clinical trials?

SK: I think one of the big ones that probably a lot of people have heard is that there’s a cure for cancer, and that the big pharmaceutical companies are hiding that so that they can continue to make money off of cancer treatment.

When you really break that down, that theory would go against a lot of moral and ethical obligations in the health care community. It would directly go against the Hippocratic Oath that physicians take. And everybody knows someone with cancer, so it would really conflict with personal interest and also our life’s work.

I’ve had people say, “I need treatment, not a placebo. I don’t want to be a guinea pig.” I really try to share information and educate people around what the truth is about those statements.

LM: Are there placebos in clinical trials?

SK: Generally, clinical trials can use placebos. In clinical trials for cancer care, we rarely use placebos. It would be unethical to not treat someone that needs treatment for cancer.

When placebos are used in cancer clinical trials, often it’s when you’re doing a randomized comparison of the standard care and the new medicine. The trial’s looking at a question like: “If we add a new medicine to our standard of care, will it make the outcomes better?” And so that’s really where placebos are often used in cancer treatment trials.