The overturning of Roe v. Wade and the end of legal abortion in Wisconsin has some people wondering about the potential impact on assisted reproduction like in vitro fertilization, or IVF.

Twin Lakes resident Becky Rosenow recently reached out to Wisconsin Public Radio’s WHYsconsin, asking us if fertility care, including IVF, would be affected.

“That’s what gave us our son,” Rosenow said in a follow-up interview. “To me, that’s a miracle of modern science.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

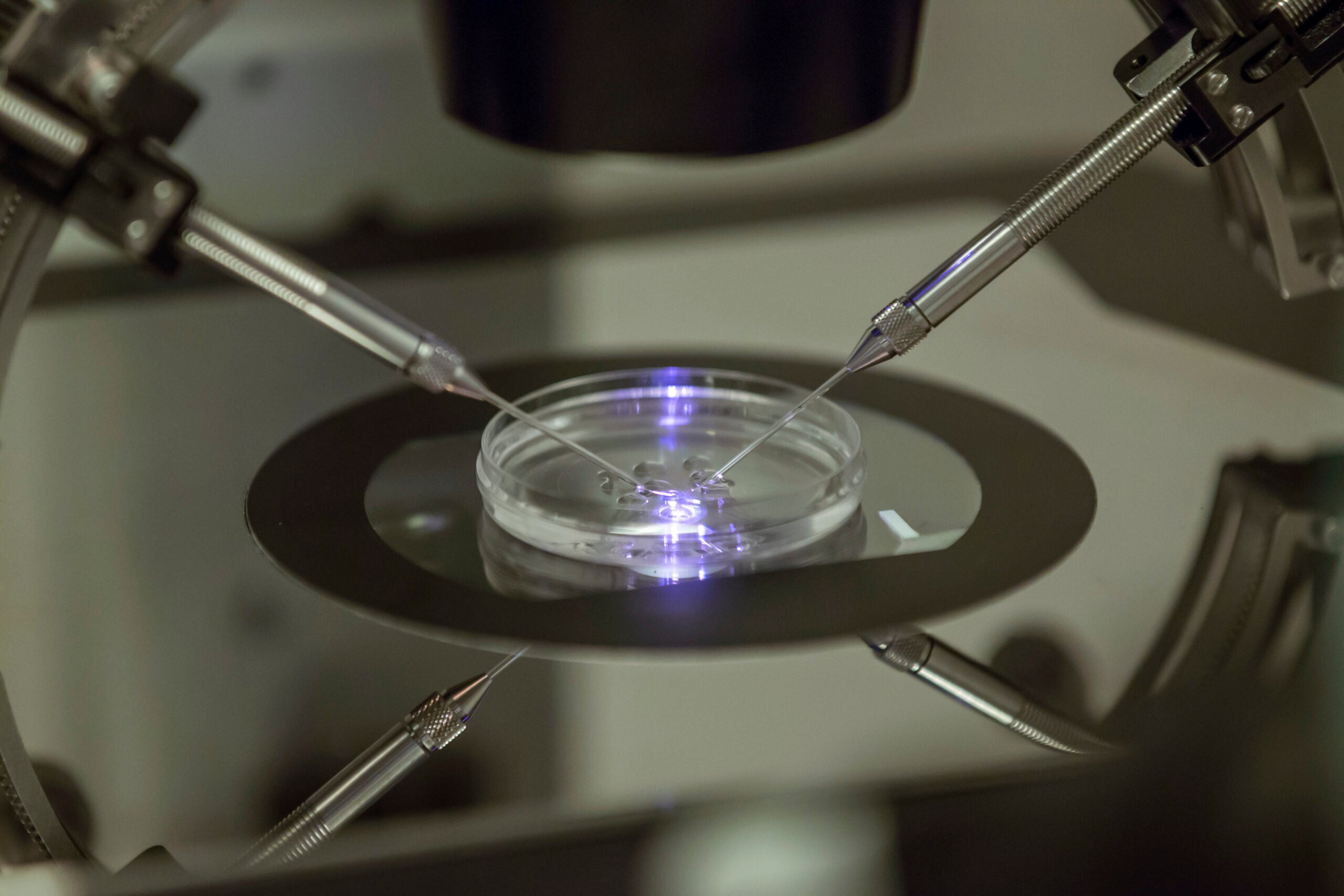

In vitro fertilization is a medical process in which an egg is fertilized outside of the body in a lab, then implanted in a uterus or frozen for future use. It is used to treat infertility, for patients who have cancer or other medical threats to their future fertility, and for LGBTQ couples hoping to conceive a child.

For each attempt at an IVF pregnancy, a large number of embryos can be created in the lab. That process is one reason people involved with infertility treatment are concerned.

According to Sean Tipton, chief advocacy and policy officer for the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, or ASRM, Wisconsin’s 1800s-era ban on abortions should not affect IVF, “at least up until the pregnancy is established.”

As of right now, Tipton said, IVF and all the processes it entails is legal in all 50 states. Regarding Wisconsin specifically, he said the 1849 law “clearly does not speak to anything about the in vitro fertilization process, and obviously couldn’t have because it was … years before that process was invented.”

In a written statement, a representative from UW Health said IVF is continuing as normal.

“The Dobbs decision does not affect fertility treatment in Wisconsin,” the statement said. “UW Health will notify patients directly should anything about their fertility treatment change, including future changes in the law.”

A ‘slippery slope’

Still, Tipton said the Supreme Court’s decision does make it a frightening time for fertility patients and providers alike. Without the constitutional right to privacy, Tipton said state legislatures now have the power to ban IVF if they so choose. Tipton said the ASRM is not aware of any legislators in Wisconsin or elsewhere planning to do that but still worries that it could be a potential unintended consequence of future potential poorly-worded abortion legislation.

“I do worry that state legislators looking to score points with their political masters in the forced birth community will inadvertently write an abortion ban that interferes with reproductive care,” he said.

The connection is the definition of when life begins, said Dr. Kara Goldman, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University and medical director of the fertility preservation program there.

“If you define life as beginning at conception or fertilization, you are saying that this embryo that we have in the laboratory may be subject to the same definitions that are being applied to abortion bans,” she said. So while Wisconsin and other states may not have laws that apply to IVF right now, she worries that it’s a “slippery slope.”

“The rug has been pulled out from under us,” she said. “This sense of security that all of these reproductive freedoms we were kind of taking for granted for so long … I don’t think we can take any of this for granted anymore.”

A common misunderstanding about IVF, Goldman said, is the sheer number of embryos which must be created to achieve success.

“An embryo, more often than not, will not achieve a pregnancy.” she said. “It takes a huge proportion of embryos to actually yield a healthy baby.”

Some embryos will lead to a failure to implant, miscarriage or lethal fatal anomalies, she said. These unhealthy embryos are usually discarded. Although this mirrors the natural attrition that takes place inside the body, she said, she worries that the legality of manipulating and discarding these embryos could be called into question.

“Access to fertility care is on the exact same spectrum as access to abortion care,” she said. “It’s all about being able to access the care you need to achieve your reproductive goals, whether it’s not to be pregnant right now, or to be pregnant later on, or not to ever be pregnant.”

‘The future of our lives and of our family’

After trying for a baby for about four years, Rosenow decided to try IVF. Her son was born a year and a half ago.

“It takes a huge toll on your body,” Rosenow said, not to mention the emotional and financial burdens of IVF.

Rosenow had what she calls the “lucky outcome” of having embryos left over after the process, and they are stored at her fertility clinic in Illinois, where abortion remains legal.

“That brings us a little bit of relief,” she said. “If our embryos were in Wisconsin, I think I would definitely be nervous at this point.”

The ASRM is not currently recommending that patients move frozen embryos to other states at this time, and Tipton said people shouldn’t make hasty decisions while the future status of IVF is ambiguous in many states.

Still, Rosenow understands why some patients may consider moving their embryos to a state they think is safer. The stakes are too high.

“Those little embryos sitting in the freezer … could someday be our son’s brothers and sisters,” she said. “It represents just so much of the future of our lives and of our family.”

This story came from a question as part of the WHYsconsin project. If you have a question about abortion access and reproductive rights, submit your question below or at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it in a future story.