After their son died in January, Jackie and Robert Watson found a stack of popsicle sticks in his Milwaukee apartment. He’d written an affirmation on each one.

While working with a drug counselor, Brandon Cullins wrote a series of affirmations on popsicle sticks. These are just a few of the phrases Jackie and Robert Watson found at their son’s apartment after his death. Photo courtesy of Robert and Jackie Watson

“I am a fighter.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Don’t sweat the small stuff.”

“My kids love me.”

Their son, Brandon Cullins, had been working with a drug counselor, who advised him to write the messages to himself. For the Watsons, it was a window into how hard their son had worked to kick his battle with cocaine. Picking up the popsicle sticks, the Watsons wondered why Cullins didn’t tell them he needed help.

“Like other parents who have lost their children to drugs, we’re now left with a number of questions,” Robert said. “Why wasn’t the love of his family enough for him to get better and fight his addiction? What could we have done differently to keep this from happening? We can only speculate on the answers to these questions; but nonetheless, they will continue to haunt us.”

Cullins, 31, is one of 514 people living in Milwaukee County to die of an overdose this year.

Cullins was found by a maintenance worker in his southside apartment. The Milwaukee County medical examiner’s office said he died Jan. 16, 2020 from an overdose of cocaine mixed with fentanyl. Cullins is one of 338 people in the county to die from fentanyl or a combination of fentanyl and another drug. His death, like thousands of others, came after years of fighting his addiction.

Wisconsin’s opioid epidemic hasn’t gone away during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Milwaukee County and elsewhere, in some ways it’s gotten worse, as social isolation has led to depression and anxiety for some, and as those who accidentally overdose may not be with others who can get them the help they need.

Ups And Downs

The Watsons said they aren’t exactly sure when their son started using drugs. He was expelled during his junior year of high school for dealing drugs.

Jackie said she believes he wasn’t using them then, but it was clear he was struggling.

Like many who deal with addiction, Cullins had ups and downs. He had three young children, Braylon, Aidan, Isabella, and loved being a dad, Jackie said.

Robert said even at his lowest, Cullins made others feel acknowledged and special.

“Brandon had a contagious smile,” Robert said. “His outgoing personality was one of his greatest characteristics and it served him well throughout his life. He was always respectful of others and always showed gratitude and appreciation for the help he received.”

The Watsons helped Cullins move into his own apartment for the first time eight months before his death. They helped him decorate, buying him a mattress and dishes, and bringing over a television and some DVDs.

They thought he was doing OK.

Opioid Overdose Deaths On The Rise

This year, opioid overdoses and fentanyl deaths are at record highs in Milwaukee County as well as statewide.

As of Dec. 7, there were 449 confirmed overdose deaths and another 65 overdose cases pending further toxicology, which would bring the total to 514, according to the medical examiner. The total number of overdoses in 2019 in Milwaukee County was 418, said Karen Domagalski, operations manager at the Milwaukee County Medical Examiner’s office

Of the deaths this year, 384 were opioid related and 338 of those were fentanyl related. The county had 244 fentanyl-related deaths in 2019, up from 188 fentanyl-related deaths in 2018, said Domagalski.

Dr. Elizabeth Salisbury-Afshar, visiting associate professor of family medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, said fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin.

“People often are being told that they are buying heroin but then what they are actually getting is fentanyl,” Salisbury-Afshar said.

Fentanyl is a medication that can be prescribed for pain. But what police and medical examiners are increasingly seeing is most of the fentanyl that is being sold on the streets is being produced in labs overseas, Salisbury-Afshar said.

“What happens is someone is used to using real heroin, and they get fentanyl, and they aren’t expecting it, and they use their normal amount and instead they get a much more deadly formulation,” she added.

Todd Smith is the special agent in charge of the Chicago Division of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

He said beginning in about 2012, the DEA began seeing organized criminal networking groups in Mexico putting fentanyl into heroin to make it stronger.

“There is only so much heroin to produce, and if they are able to add synthetic fentanyl to the heroin, then they are able to put more heroin on the streets to meet demand,” Smith said. “Unfortunately, more users are chasing a high and the cartels want to put the strongest heroin on the market.”

That has, in return, increased overdoses across the United States and in Milwaukee County, Smith said.

Smith said just 2 milligrams of fentanyl can be deadly.

“If you think about a penny, 2 milligrams is what actually fits on the cheek of Abraham Lincoln,” Smith said. “So, it is a very small amount that is a potential lethal dose.”

Pandemic-Related Isolation Makes Relapses More Dangerous

Salisbury-Afshar said the coronavirus pandemic could be exasperating the problem of opioid overdoses, although there is a lag in collecting that data. While Milwaukee County has a lab on site, other counties do not. In Dane County, the data lags by about six months, according to the Dane County Medical Examiner’s Office.

Between January and June, the Madison Police Department received 139 overdose calls, compared to 102 in the same time period in 2019 — a 36 percent increase, according to data obtained by UW Health.

Salisbury-Afshar said the pandemic has increased many mental health and financial issues, and been detrimental for people with substance use disorders.

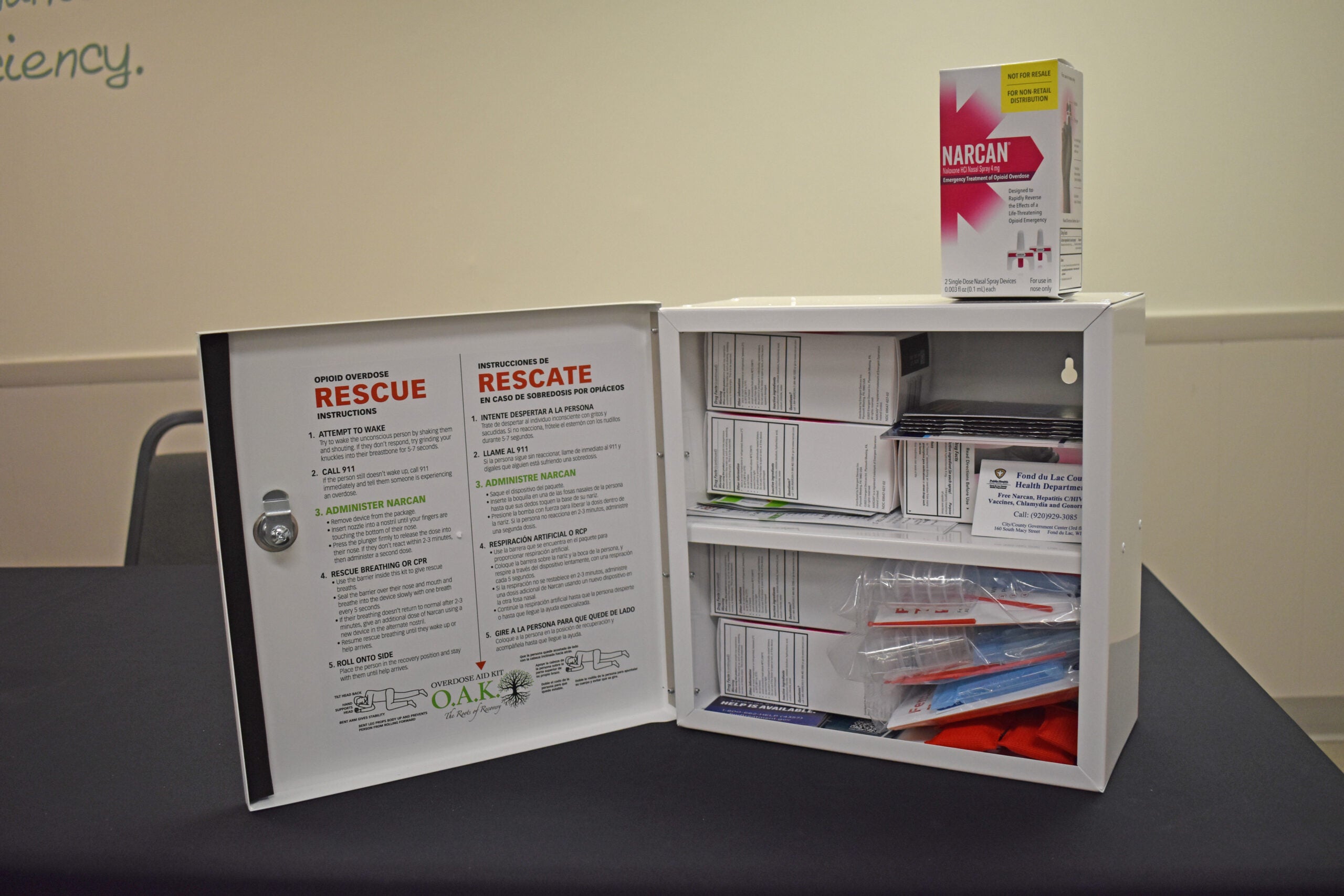

“Isolation is particularly dangerous because if you have an accidental overdose, there will be no one there to respond to administer Naloxone or to call 911,” Salisbury-Afshar said.

Naloxone, sold under the brand name Narcan, is a medication designed to rapidly reverse the effects of an opioid overdose.

[[{“fid”:”1396851″,”view_mode”:”embed_portrait”,”fields”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EBrandon%20Cullins%20celebrates%20his%2030th%20birthday%20while%20out%20to%20breakfast%20with%20his%20parents.%20%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Robert%20and%20Jackie%20Watson%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Brandon Cullins out at breakfast”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Brandon Cullins out at breakfast”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EBrandon%20Cullins%20celebrates%20his%2030th%20birthday%20while%20out%20to%20breakfast%20with%20his%20parents.%20%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Robert%20and%20Jackie%20Watson%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Brandon Cullins out at breakfast”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Brandon Cullins out at breakfast”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Brandon Cullins out at breakfast”,”title”:”Brandon Cullins out at breakfast”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]Cullins had overdosed twice before, but friends helped him survive. When he moved into his own apartment, his parents did worry he would relapse, but they wanted to have faith in their son.

“We were worried, because he was on his own,” Cullins’ father, Robert, said, “and our biggest fear came true. He overdosed and no one was there to help him.”

Cullins’ mom, Jackie, believes he didn’t intend to die.

The popsicle sticks with their messages of affirmation were displayed during his funeral and empty sticks were available for people to write their own words about Cullins. The Watsons now keep those at their house to remember their son.

“Almost a year later and it doesn’t seem real because he was so full of life, and he was so happy, and he was trying,” Jackie said. “He was struggling but he was trying. He was ashamed and didn’t want us to know it. I just wish he could have come and said he needed help.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.