In this Wisconsin Public Radio series, “How We Got Here: Abortion in Wisconsin since 1849,” WPR reporters explore how the state’s 1849 abortion ban came to be and how Wisconsinites have lived with and without it since.

__________________________________________________________________________

For more than a year now, Wisconsin has been operating under an abortion law that was first written and passed more than 170 years ago.

Last June, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its historic opinion in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case, overturning Roe v. Wade and leaving the legality of abortion up to individual states, that little-known Wisconsin law went into effect.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

That law — which was written just one year after Wisconsin became a state — effectively bans abortions. It quickly became the focus of countless protests across the state when it went back into effect last year, as many decried it as being antiquated. A challenge to the law is being heard in Dane County Circuit Court now, and could be making its way to the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

At WPR, we’ve been researching how, and why, that law was passed, and what it means for people today. WPR reporters have spent months looking into what was happening in Wisconsin, and across the nation, regarding abortion when the law was passed.

While the letter of the law in Wisconsin remains the same, the medical understanding of abortion and moral debate around it is fundamentally different now than it was at the time the law was made.

Abortion in the 1800s

Finding out you were pregnant in 1849 looked very different than it does in 2023. There were no pregnancy tests, so missing your period was only a first sign. It wasn’t until you could feel the baby kicking that you would know for sure.

Still, people at that time who didn’t want to be pregnant had options. There were people who would perform abortions — “abortionists,” doctors, midwives — and there were also well-known home remedies.

Historians agree that people sought abortions at the time Wisconsin first passed an abortion ban — in fact, it may have been quite common.

According to historian James Mohr, a history professor at the University of Oregon and the author of “Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy,” abortion rates were increasing throughout the 19th century across the nation.

“It was very widespread,” he said.

Still, abortion was a different experience in the mid-1800s than it is today. While abortions could be performed by doctors or “abortionists,” they were often carried out at home, said Kimberly Reilly, history and women’s and gender studies professor at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay.

Some home medical journals had instructions for “restoring the menses” or remedying “the most serious form of female complaint,” she said. “Everybody would know what you meant by it.”

Without pregnancy tests or ultrasounds to prove someone was pregnant, some historians say people in this time may not have considered early abortion to be ending a pregnancy, per se.

“The lines that we have today, these really kind of bright lines, are just kind of blurred at that point,” said Reilly.

If there was a bright line, it was the mother feeling those fetal movements. This was known as “quickening” and was significant both medically and legally at the time.

Wisconsin’s law was part of national effort to ‘professionalize’ medicine

Wisconsin officially became a state in 1848, and the first prohibitions on abortion in Wisconsin were introduced in a bill relating to homicide just one year later, according to the Legislative Reference Bureau.

According to Mohr, there were a number of states passing laws that restricted abortion throughout the mid-1800s, including Michigan, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York and Massachusetts.

Wisconsin’s abortion law, which was narrowly passed by the Assembly on March 10, 1849, as a part of a bill related to homicide, used almost the exact language of a Michigan law. This was happening, of course, at a time before women had the right to vote.

Mohr calls the spread of abortion bans a “medically-driven crusade.” In the nascent days of the American Medical Association, physicians were attempting to crack down on medicine being performed by people outside their ranks, and that included performing abortions.

“There was an effort to try to make abortion illegal and especially to drive what the … so-called regular physicians regarded as quacks from the field, on the grounds that they were dangerous and they were hurting women,” he said.

The ‘quickening doctrine’

Under Wisconsin’s original 1849 abortion ban, abortion was only illegal after quickening. The law deemed “the willful killing of an unborn quick child” to be manslaughter.

A number of states’ early abortion bans followed the so-called “quickening doctrine,” or the idea that terminating a pregnancy before quickening was not a criminal act.

“Since quickening was the accepted proof of pregnancy, in effect these laws did not ban abortions in the first half of pregnancy,” Mohr said.

But a key change to Wisconsin law in 1858 made it into what remains on the books today — a ban of virtually all abortions no matter the gestational age.

Looking back at that history, Reilly said she was “immediately struck by the deep irony” that people between 1849 and 1858 had more rights to terminate a pregnancy than they do under today’s law in Wisconsin.

A key change shapes today’s abortion ban

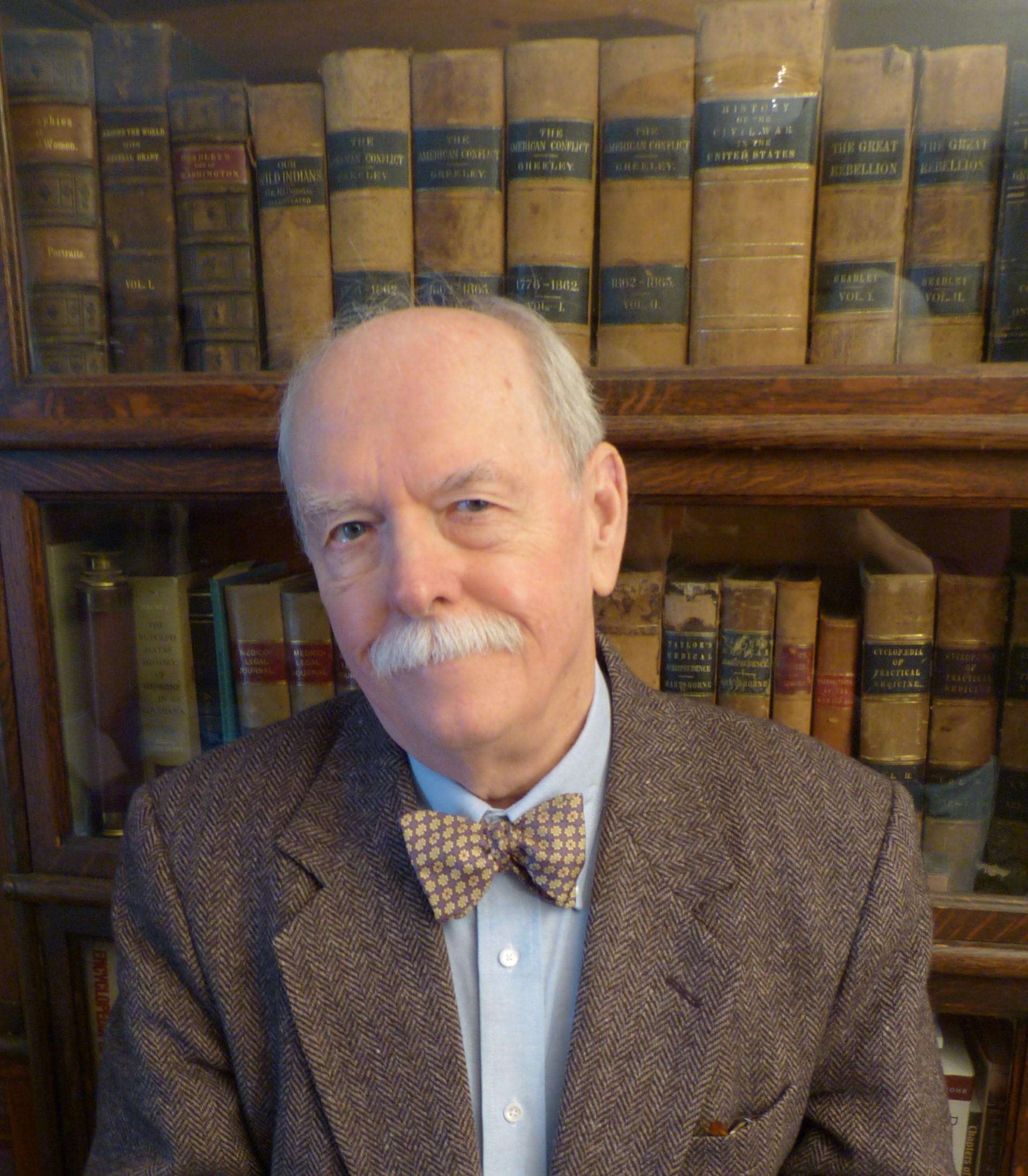

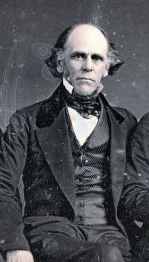

The shift away from the quickening doctrine in Wisconsin is largely credited to state Senate clerk, physician and abolitionist William Henry Brisbane.

Brisbane was born in South Carolina in 1806 and eventually settled in Arena, Wisconsin.

Historians believe he was responsible for removing the word “quick” from the law, turning it into the abortion ban that we have today.

In 1857, Brisbane wrote to leading anti-abortionist Horatio Robinson Storer that he intended “to get a law passed by our Legislature to meet the case, much too common, of administering drugs and injections either to prevent conception or destroy the embryo,” according to the Legislative Reference Bureau. The law was changed in 1858, and Brisbane claimed credit for pushing the change through in an 1859 letter.

Still, Brisbane’s exact motivation remains murky and may be lost to history.

Brigid Nannenhorn is a UW-Madison doctoral student researching abortion history in the state. She said his writings available at the Wisconsin Historical Society archives don’t provide any clues.

“In his diaries, he talks about anti-slavery, he talks about temperance, he talks about gambling,” she said. “He does not mention abortion, he does not mention miscarriage, infanticide.”

Although Brisbane was a pastor, Mohr said a religious drive to restrict abortion would have been unique at the time. Most of the political movement was driven by the desire to professionalize medicine, he said.

“It is almost impossible for Americans today to think of abortion as an issue that was not tied to religion,” he said. “But in the 19th century, it was not tied very closely to religion. That is, it was a medical question. It was not a religious or a moral question.”

Brisbane was likely so influential due to his position as clerk.

“People like Brisbane get the ear of the committee,” Mohr said.

Abortion wasn’t a major political issue that captivated the public the way it is today, he said.

“These were not public campaigns,” Mohr said. “They were campaigns conducted by elite physicians, who had the ear of legislatures, and were able to suggest that this was necessary legislation.”

The ban remains

In the years following 1858, the law was never taken off the books, which is why all abortion providers immediately ceased operations in the state last summer.

Just days after the Dobbs decision, Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul filed a lawsuit seeking to repeal the law.

The case could ultimately be decided by the state Supreme Court, which has its first liberal majority in 15 years after Justice Janet Protasiewicz was seated Aug. 1.

For more from “How We Got Here: Abortion in Wisconsin since 1849,” visit wpr.org/1849.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.