In this Wisconsin Public Radio series, “How We Got Here: Abortion in Wisconsin since 1849,” WPR reporters explore how the state’s 1849 abortion ban came to be and how Wisconsinites have lived with and without it since.

__________________________________________________________________________

Over the last year, access to abortion in Wisconsin has been almost nonexistent.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling returned the state to a law that bans the procedure in nearly all cases.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul has filed a lawsuit in state court, arguing the abortion ban that dates back to 1849 is too old to be enforceable. Until that case is heard, doctors and health care systems have been cautious not to provide care that’s now considered illegal.

But some historians and legal experts agree that the law likely didn’t prevent abortions from taking place the first time it was in effect.

Marquette University Law School professor Lisa A. Mazzie told WPR “the law on the books and the law on the ground are sometimes two different things.”

“The way that people operate in light of the law is also very interesting,” Mazzie added. “So we know that since 1849, there was a law that prohibited abortion, and we know still, women were obtaining abortions and doctors were providing them.”

A researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison surveyed available county court records from 1849 to 1900 and found prosecutors brought criminal charges under the abortion law 17 times. Of those, only five ended in guilty verdicts.

Mazzie said a prosecutor’s views on abortion could have definitely influenced whether they wanted to bring a case to trial. But she added there was a simpler explanation as to why law enforcement didn’t often pursue them.

“That procedure is inherently a very private, personal one,” Mazzie said. “So in order to find out that it has happened, you need people to tell law enforcement, to tell somebody that a potential crime has occurred.”

If everyone involved kept the procedure to themselves, law enforcement would likely never know that it happened at all.

The cases that were brought under the state’s abortion law were often ones in which a pregnant person died.

Lauren MacIvor Thompson, assistant professor at Kennesaw State University, studies the history of birth control and abortion in the early 20th century. She said across the country, there wasn’t a widespread effort to enforce abortion bans until the mid to late 1940s, after the Great Depression and World War II.

“You see a real demographic shift in terms of women working outside the home — they return to the home to be homemakers,” MacIvor Thompson said. “So that’s when you see police forces in local jurisdictions really starting to crack down on illegal abortions in a way that they really weren’t doing in the 1920s and ’30s.”

A case in Milwaukee in the 1940s could be an early example of that effort, and one that highlights how prosecutors handled cases that MacIvor Thompson described as medical malpractice.

Medical advancements, societal changes impact some decisions to end pregnancy

In 1943, Hazel Williamson traveled to Milwaukee with a list of three doctors from her fiancé of 12 years. The 34-year-old was a farmer’s daughter, active in the Waunakee Women’s club and one of many women working in a factory during World War II. During her trip to Milwaukee, she was also between two and five months pregnant. She chose the first name on her list: Dr. Edmund Timm.

Timm, who was 68 years old, had reportedly practiced medicine on Milwaukee’s North side for 45 years.

After their initial meeting, Timm took Williamson to what was called a “lying-in home,” a type of rooming house used by people seeking an abortion. The one Williamson stayed at was operated by a practical nurse who had previously been fined for performing an abortion. Local newspapers later reported at least five abortion patients were staying there at the time.

Two days after arriving in Milwaukee, Williamson underwent an operation by Timm at his office. A state Supreme Court decision said Williamson told another woman that Timm was “like a horse doctor,” that he had treated her roughly and the operation hurt her. That evening, she started running a fever.

Two days after the initial operation, Timm performed a second procedure on Williamson. Court records describe her as being very sick by this point. Early the next morning, Williamson died from sepsis and a uterine hemorrhage. An autopsy found she had lacerations on her vagina and her cervix was punctured.

According to testimony from the practical nurse, Timm arrived at the lying-in home shortly after Williamson’s death. But before he called the coroner, he went through Williamson’s purse to find the list of doctors and ripped his name off the top.

Timm was later charged with second-degree manslaughter under the state’s abortion law. For his defense, Timm’s attorneys tried to argue that Williamson had already received an abortion prior to coming to him and that he was merely providing care in the aftermath. He claimed the state had no evidence the fetus was alive when Williamson arrived in his office.

But his trial judge — and eventually the Wisconsin Supreme Court — found that Timm was not credible and his testimony had been impeached, or discredited, many times throughout the trial.

While Williamson’s case ended in tragedy, MacIvor Thompson said surgical advancements meant abortion procedures were increasingly safe by the 20th century.

“We do start seeing more surgical abortions being performed in the early 20th century than we did in the 19th century,” MacIvor Thompson said. “In fact, by the 1930s, surgical abortion is actually pretty safe.“

She said that meant more people were going through underground channels like the one described in this case, instead of using herbal concoctions or other at-home remedies.

Williamson’s case also highlights the impact of societal context on many people’s decisions to end a pregnancy, according to MacIvor Thompson.

If Williamson had been engaged for 12 years, that would have been during the height of the Great Depression, a time when many people were putting marriages and starting a family on hold because of high unemployment. In 1943, the U.S. was involved in WWII and had reinstated the draft, creating more uncertainty for those considering starting or adding to a family.

MacIvor Thompson said societal norms around extramarital sex were also a major factor.

“The 1940s are functionally not very much different than the 18th or 19th century when it comes to out-of-wedlock births,” she said. “In some ways, they’re almost worse, because at least in the colonial period, people might have been able to look the other way. But by the 1940s and 1950s, to have a child out of wedlock was really a very serious social issue for women.”

The same social stigma likely drove many women in earlier decades to perform abortions on themselves or try home remedies passed on by friends and family.

Abortion was ‘a knowledge that was shared by women’

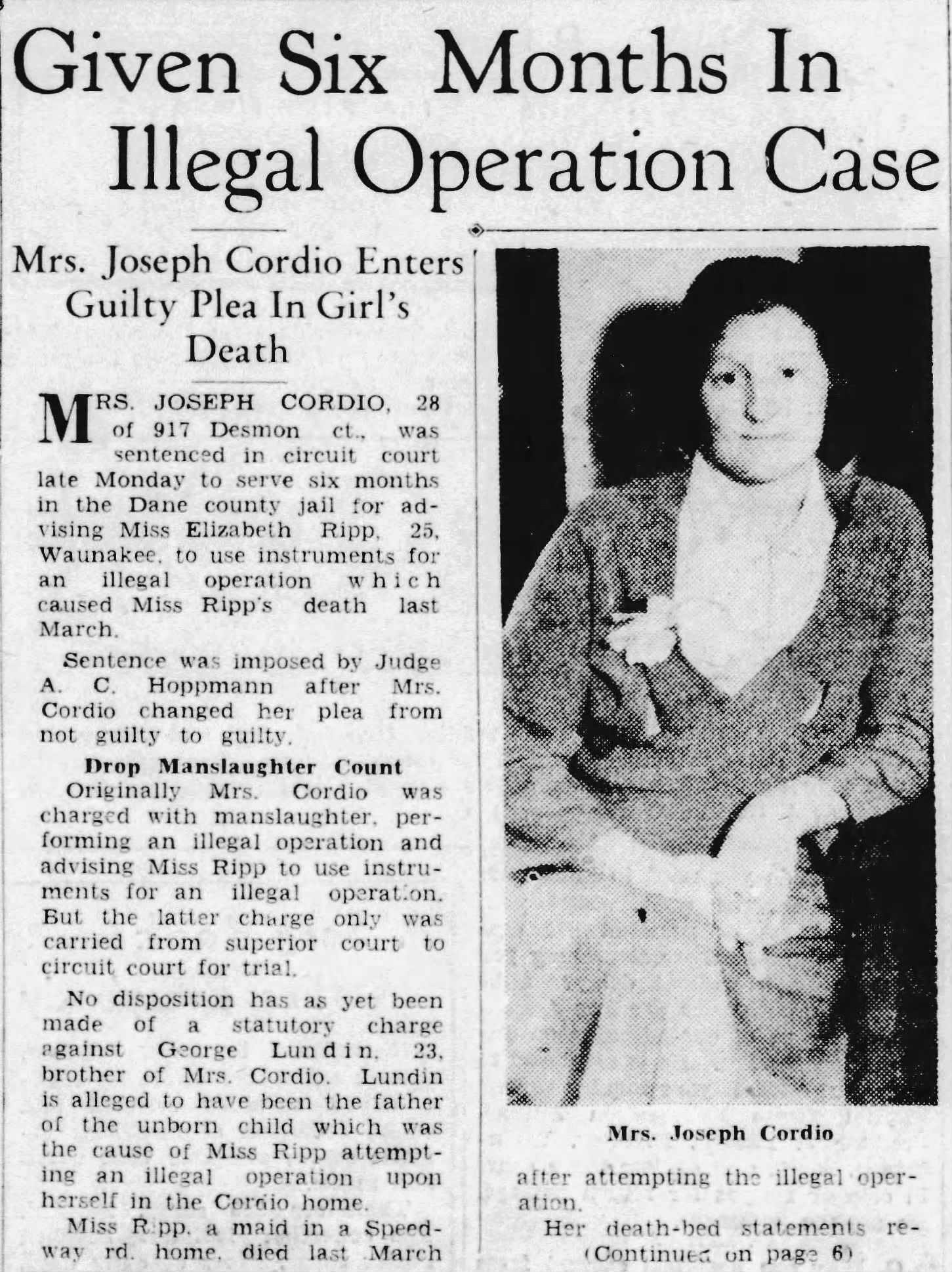

Mrs. Joseph Cordio, a 28-year-old woman from Madison, was initially arrested on a charge for performing an illegal operation on another woman in March 1933. Newspapers only refer to by her husband’s name, but an obituary for her husband more than 20 years later shows that her first name was Lilly.

At the time of her arrest, police claimed that Cordio had performed an abortion on Elizabeth Ripp, 25. Ripp was the girlfriend of Cordio’s younger brother and had been hospitalized after a miscarriage earlier that month. The Wisconsin State Journal reported that police questioned her just hours before she died, and she implicated Cordio in the abortion.

At the time of her arrest, Cordio admitted to telling Ripp how to induce a miscarriage and what instruments to buy to do it. Police reported finding the same types of instruments in Cordio’s home prior to her arrest.

But MacIvor Thompson said it’s not surprising that Cordio would own these tools. She said many women had dilation instruments and uterine probes at home to treat reproductive health problems like a prolapsed uterus.

“You could order those from like the Sears catalog or any drugstore,” she said. “Yes, those things can be used to perform an abortion on yourself, but they also were used to treat themselves at home for vaginal and uterine problems that you weren’t necessarily going to go visit a physician for, particularly if you lived in a rural area.”

According to local newspapers, Cordio said she told Ripp it was dangerous to induce a miscarriage and maintained that she wasn’t involved in the procedure itself. She said Ripp came to her house, went into her bathroom and a few minutes later, came out and announced she had done it.

The newspaper reported that Cordio was initially charged with second-degree manslaughter for Ripp’s death on top of other charges for performing an illegal operation and advising Ripp to perform the illegal operation. But only the last charge made it to trial, where Cordio pleaded guilty and was sentenced to six months in county jail.

“It really does speak to the idea that inducing one’s own miscarriage is something that was a knowledge that was shared by women, passed down at the kitchen table over cups of coffee,” MacIvor Thompson said. “You would share what methods had worked for you in the past, and you would share that with female friends or family members.”

But Mazzie said Cordio’s case also highlights the way Wisconsin’s early laws dealing with abortion tried to crack down on this shared knowledge.

A photo of Elizabeth Ripp, a woman who died after inducing a miscarriage, from The Capital Times on Monday, March 20, 1933. Photo from Newspapers.com

“It serves as a warning in some ways,” Mazzie said. “If my friend comes to me and asks me if I know how to help her out of her situation, I’d have to figure out whether I’m willing to take the risk of giving her any suggestions.”

These laws, described as “Offenses against Chastity, Morality, and Decency,” were created in 1858 at the same time that state lawmakers revised the original abortion ban. They banned people from “producing a miscarriage,” which included administering an abortion, as well as advising or procuring an abortion for a person. They also stated that any woman who sought an abortion could be imprisoned for up to six months and fined.

But the statutes allowed at least one physician to receive a lighter sentence than he would have under the state’s abortion ban.

Restrictions on state abortion ban stick around long after lawmakers try to remove them

Anna Jung is only described in the Racine Journal-News as “an unmarried female who resides in the county outside of the city.” Court records show she was six to eight weeks pregnant when she underwent an abortion and was hospitalized after the procedure.

Jung lived, but law enforcement found out about her case. Jung’s testimony is what led to the arrest of Dr. A.M. Foster of Racine in 1922.

In the first article about his arrest, Foster claimed he did not perform an abortion. But a jury found Foster guilty of second-degree manslaughter.

Foster then sued the state. He claimed there wasn’t enough evidence he performed an operation. But Foster also alleged that even if he had performed the operation, he shouldn’t be convicted under the state’s abortion law and instead should be tried under Wisconsin’s morality laws because Jung’s pregnancy was so early on.

The state Supreme Court agreed with Foster. The justices’ opinion said, “A two months’ embryo is not a human being in the eye of the law and therefore its destruction constitutes an offense against morality and not against lives and persons.”

Mazzie said the fact the state Legislature had created two different laws related to performing an abortion meant the court had to assume the two statutes were not for the same offense.

The decision also revived the legal doctrine that the state’s abortion ban only applied after what was known as the “quickening,” a point in mid-pregnancy when fetal movement can be felt by the pregnant person. The original language of the ban in 1849 stated the law applied to a “quick” child, but lawmakers removed the word in 1858.

“The Legislature doesn’t change the statutes (after the Foster decision), then everyone goes forward assuming that, OK, these two statutes mean what the court said,” she said. “That’s kind of the way the law went until we get into the 1950s.”

In 1955, a new criminal code went into effect and combined all the statues related to abortion under one statute, where it remains today. At that time, lawmakers also clarified an “‘unborn child’ means a human being from the time of conception,” negating the Foster v. State decision. Penalties for a pregnant person seeking an abortion, which were first created through the morality laws, remained in statute until 1985 when lawmakers prohibited their enforcement before they were repealed in 2011.

Now that Wisconsin has returned to many of the same laws that influenced Cordio, Foster and Timm’s legal cases, Mazzie said the uncertainty around abortion has returned, as well. She said even with medical advancements around the procedure, she thinks many of the same problems with enforcing the law are still present today.

“In the era of medication abortion, being able to find out who does what to end a pregnancy in their own home would be difficult without people who are going to tell on you,” Mazzie said. “How are you going to enforce (the law)? To what lengths will the state go or want to go to get the evidence it needs to enforce it? And are we all going to be OK with that?”

The private nature of abortion procedures became a major component in lawsuits around the country through the late 1960s that eventually culminated in the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe V.s Wade decision.

For more from “How We Got Here: Abortion in Wisconsin since 1849,” visit wpr.org/1849.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.