When Kathy Waligora learned she was pregnant in November 2018, she started imagining what it would be like to be a mom. But at her eight-week appointment, the nurse couldn’t find a heartbeat. Waligora was having a miscarriage.

She and her husband continued trying to get pregnant but had little luck for nearly a year after her miscarriage. Not wanting to give up on building a family, they looked to fertility treatment. But Wisconsin’s lack of insurance coverage for infertility services made the path forward complicated.

“Being stuck for four years — in this suspended reality of trying to be pregnant, trying to stay pregnant, trying to navigate expensive fertility treatments — it would be impossible not to consider what your life is like without children,” she said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Waligora is one of about 6 million women ages 15-44 in the United States to deal with infertility. In Wisconsin, there are more than 172,000 women struggling with infertility.

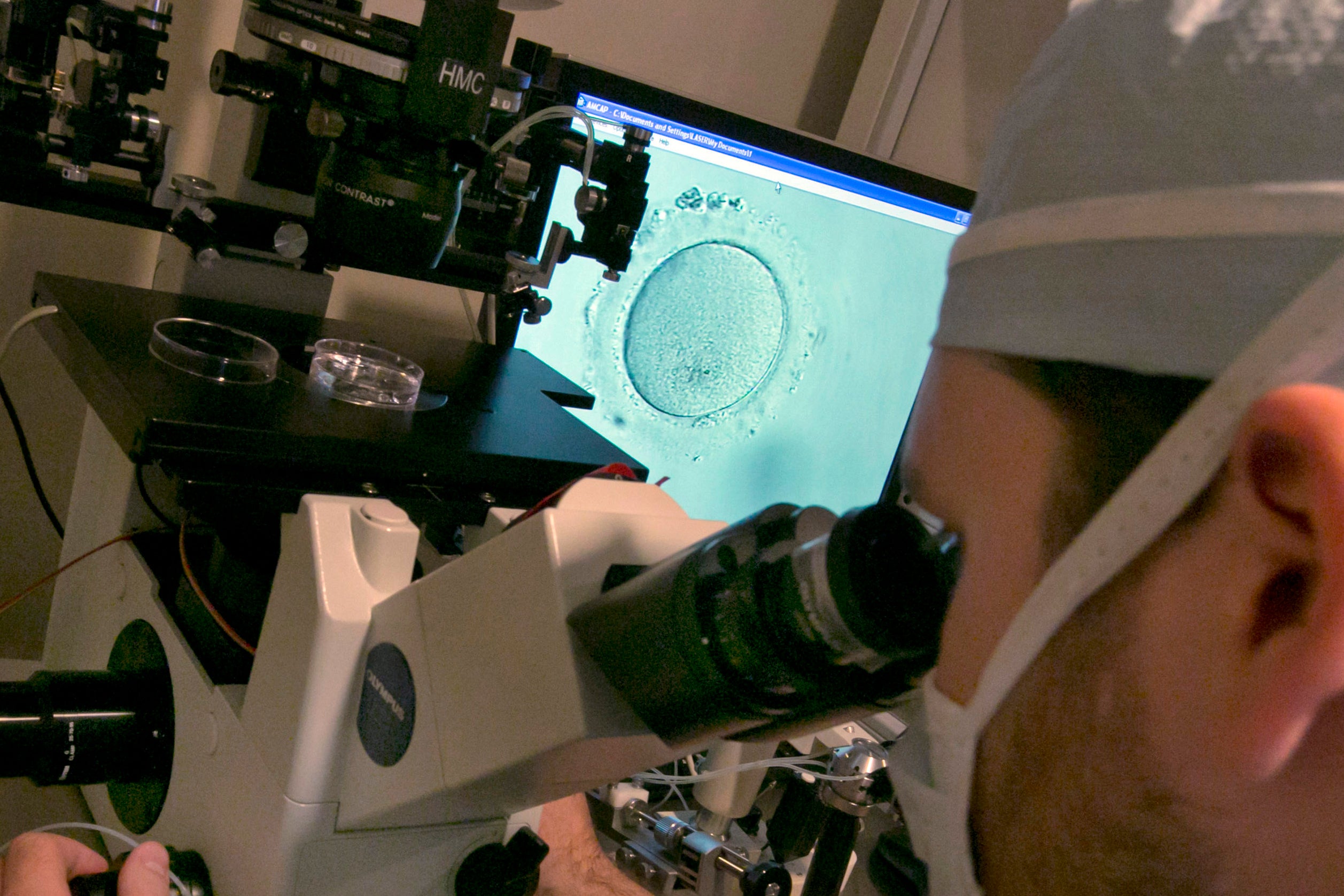

Infertility is considered a disease by the World Health Organization, American Medical Association and American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. It’s defined as the inability to conceive after a year or more of regular, unprotected sex.

But under current state law, no health insurance policy is required to cover infertility services. In vitro fertilization, or IVF, costs can range between $10,000 to $25,000 for one cycle, depending on the location, the Washington Post reports.

Nationally, 21 states have passed fertility insurance coverage laws, 14 of which include IVF coverage according to RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association.

Illinois is one of those states. In 2018, Illinois passed a law that required health insurance companies to cover the preservation of eggs, sperm and embryos for cancer patients. And in 2021, the state extended infertility treatment coverage to LGBTQ+ families, single people and women with specific health issues.

Dr. Elizabeth Pritts is the medical director and founder of the Wisconsin Fertility Institute, which provides care and services for people with infertility. She said it took her years to set up an IVF laboratory — and that even though she’s providing a service, there aren’t enough clinics in Wisconsin to keep up with demand.

“We will never capture the entire population of couples of people that need fertility treatment because they cannot afford it,” she said.

Receiving fertility care takes an emotional, financial toll

Originally from Pleasant Prairie, Waligora and her husband were living and working in Chicago when she had her first miscarriage.

They continued trying to get pregnant, but after a year, Waligora was prescribed Letrozole, a commonly used ovulation drug. When that didn’t work, her doctor referred her to a fertility specialist. After being diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome, it became clear that IVF was likely her only option for having a baby.

Because she was living in Illinois, her fertility treatments were covered.

She prepped for three transfers over the course of a year, buying different medications that cost upward of $600. The first time, she became pregnant but lost the baby at 12 weeks due to a chromosomal abnormality. Then, she had a “chemical pregnancy,” meaning an early miscarriage. After that, she experienced a failed transfer.

“There were a lot of times where my husband and I thought, maybe we just consider a life without children. And maybe we think about how to adjust our hopes and our expectations for ourselves and live a childless life and find joy in that,” she said.

To make matters more complicated, midway through Waligora’s treatments in June 2021, she and her husband moved back to Pleasant Prairie.

“After we had been through over a year of IVF and still weren’t pregnant, we just decided to stop waiting,” she said, adding they thought, “We want to go home. We want to be closer to our family.”

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Waligora was able to continue working at her job in Chicago which had gone remote. That meant her treatments continued to be covered — so long as Waligora traveled to Chicago to get them.

For three months, Waligora woke up at 4:30 a.m. almost every weekday to drive from Pleasant Prairie to Chicago. She would get a blood draw and an ultrasound to ensure her medications were working and head back home.

Waligora finally became pregnant with her daughter Eleanor in September 2021. She was born in May 2022.

“We would not have been able to continue as long as it was necessary to treat my infertility, and I’ve no doubt without Illinois’ insurance requirements, my daughter wouldn’t be here,” Waligora said.

Even with insurance coverage, Waligora said she and her husband spent $40,000 on deductibles and copayments for fertility treatments.

Waligora called it an “all-consuming” experience. She was diagnosed with anxiety and PTSD because of her several miscarriages, something research shows is not uncommon.

“It was incredibly challenging,” she said. “And in some ways, I’ve now been on the other side for about a year since my daughter was born, and I am still processing the trauma and the grief.”

Major companies begin covering fertility treatments to attract, retain employees

Dr. Ellen Hayes is a reproductive endocrinologist who works at Kindbody Milwaukee, an IVF clinic. She said when she recommends IVF to some of her Wisconsin patients, they ask for a different treatment because it’s unaffordable.

“The ones that know that they will not have coverage for treatment have an additional layer of stress and anxiety,” she said. “They worry about what I’m going to recommend for them or what they’ll need to do because they’re worried that they won’t be able to proceed.”

In some cases, Hayes said, people take major financial risks to pay for treatment.

“They are sometimes depleting their savings, taking out a second mortgage on their home, selling a car, getting a second job,” Hayes said.

“I think it’s just taken some states much longer than others to realize that fertility care is health care,” she continued.

Research from RESOLVE found that providing coverage for fertility treatments barely affected insurance premiums — and in states that it did, increases were less than 1 percent.

Hayes added that providing fertility benefits to employees wouldn’t be a financial burden for businesses.

Walmart and Amazon, two of the largest employers in the U.S., started providing fertility benefits to employees in recent years, Axios reported. Studies also show companies who offer IVF coverage report higher employee satisfaction.

Attempts to cover fertility treatments at state level fail

In his original budget proposal, Democratic Gov. Tony Evers called for “any health insurance policy and government self-insured health plan that covers medical care” to cover all care related to infertility.

But GOP majorities in the state Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee removed that provision from the budget.

Co-Chair Rep. Mark Born, R-Beaver Dam, told Wisconsin Public Radio in an email “this item is non-fiscal policy and was removed along with other non-fiscal policies, as has been routine for the committee.”

Standalone companion bills on the issue were introduced last session, neither of which received a public hearing, according to the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau.

That means people like Maria Novotny, a researcher and leader with Building Families Alliance of Wisconsin, an advocacy group pushing for insurance coverage, are back to the drawing board.

“It just seems like more and more, Wisconsin’s not becoming a place that was really friendly to supporting the ability to form your family if alternative family-building options are needed,” Novotny said.

The issue has received renewed attention following the reinstatement of Wisconsin’s pre-Civil War abortion ban after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last year. Since then, Planned Parenthood of Illinois has reported a 12-fold increase in the number of patients from Wisconsin seeking abortion care.

Novotny said building families is a bipartisan value — and something the GOP has always backed, even calling itself the pro-family party.

“It’s really upsetting, I think, to know that it’s not being taken seriously,” Novotny said, adding it could accelerate the state’s birth decline. As of 2020, Wisconsin’s birth rate was 10.4 percent, according to state data. In 2010, it was 12 percent.

For now, Novotny said advocates are working to educate people and build an even stronger coalition of constituents from across the state to support fertility service coverage.

“Having a family and the ability to build one’s family is a right for everyone,” she said. “Infertility in the past has been described as an elite issue. But there are lots of underlying health conditions and reasons for why individuals need access to fertility care.”

Waligora is happy to have a healthy daughter, but she said other people should have the opportunity to build their families.

“There are not a lot of other medical conditions where we decide to withhold treatment from insurance plans. And infertility should not be any different,” Waligora said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.