As more Wisconsin clinics offer ketamine to treat depression, a local professor studying psychiatric treatments said the drug offers a new method for patients to try where others have failed.

Cody Wenthur is an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Pharmacy and leads a research program studying psychoactive drugs. He said ketamine is the “first wave” in the newest area of research for psychedelic-assisted therapies.

Local experts told The Cap Times recently that the Madison area had two options for ketamine treatment as of late 2021. Dane County now has at least 10. A few years ago, The New York Times reported on hundreds of clinics popping up nationally.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Wenthur recently joined Wisconsin Public Radio’s “Central Time” to explain how ketamine can treat mental illness, risks associated with the drug and what it means that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved the use of ketamine for this purpose.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Rob Ferrett: How much research has gone into ketamine as an antidepressant treatment?

Cody Wenthur: There has been a very good amount of research sponsored by large funders like the National Institute of Mental Health. Starting around the early 2000s, people started noticing that ketamine was having rapid-acting effects on people’s mood when they were getting infusions of ketamine for other approaches.

As your brain learns, it undergoes a process called plasticity, where old connections may weaken (and) new connections may form and strengthen. Ketamine seemed to be modifying those connections and helping induce neuroplasticity.

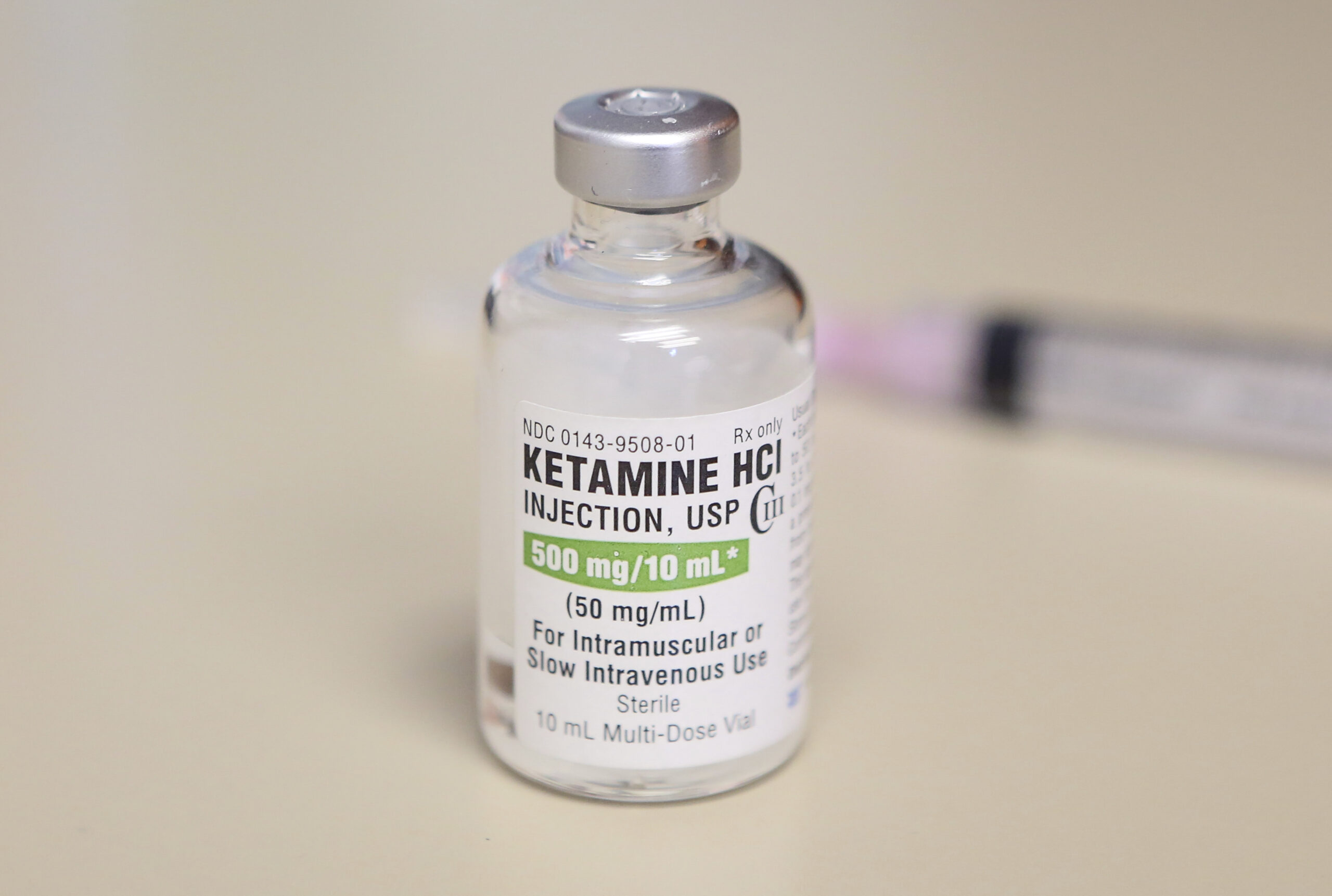

That finally culminated (in 2019 with) the approval of a particular form of ketamine, called esketamine, as an adjunct or add-on treatment for depression (in) people (who) hadn’t found relief. That’s available as a nasal spray. But because that spray has a lot of restrictions around its use, it can be quite costly.

Ketamine has been available since approximately the 1970s. Other individuals started thinking they might want to use the original formulation of ketamine.

RF: How important is finding new treatments for people who slip through the cracks and don’t find help with other existing treatments?

CW: I would argue it’s very important. We don’t want to leave people behind when people are suffering, and we’re having particularly high rates of suicidality in the world today and epidemic rates of depression and other psychiatric illnesses.

The numbers seem to indicate that about one-third of individuals will have a good response from first-line antidepressants. These are things like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. About one-third then will experience relief when another treatment is added on or their therapy is switched. But there’s about one-third of individuals who go through all the medication treatments available, some of the procedural treatments (such as) talk therapy, and they aren’t experiencing significant relief.

The other thing that’s really interesting about ketamine and potentially beneficial is the rapid-acting nature of it. In comparison to those first-line antidepressants, which often take six-to-eight weeks to work, often folks who do experience relief from ketamine — somewhere around two-thirds to three-fourths of folks who try it — they get relief within hours to days.

RF: Are there concerns about abuse or any downsides to ketamine?

CW: Yes, certainly. There are potential downsides to all drugs that we use. As a pharmacist (and) a neuropharmacologist, I like to remind people, it’s the dose that makes the poison for all compounds. Getting the right drug in the right place at the right time is vitally important, because any one of those things going wrong can cause problems.

Ketamine is a so-called scheduled drug. Under the Controlled Substances Act, compounds that have a risk of abuse have special protections on how they’re handled and used. Ketamine falls roughly in the middle of that range, which means that it has a known abuse liability or risk. But that is not quite as high as something (with) the highest risk — things like cocaine or some very strong opioids, for example.

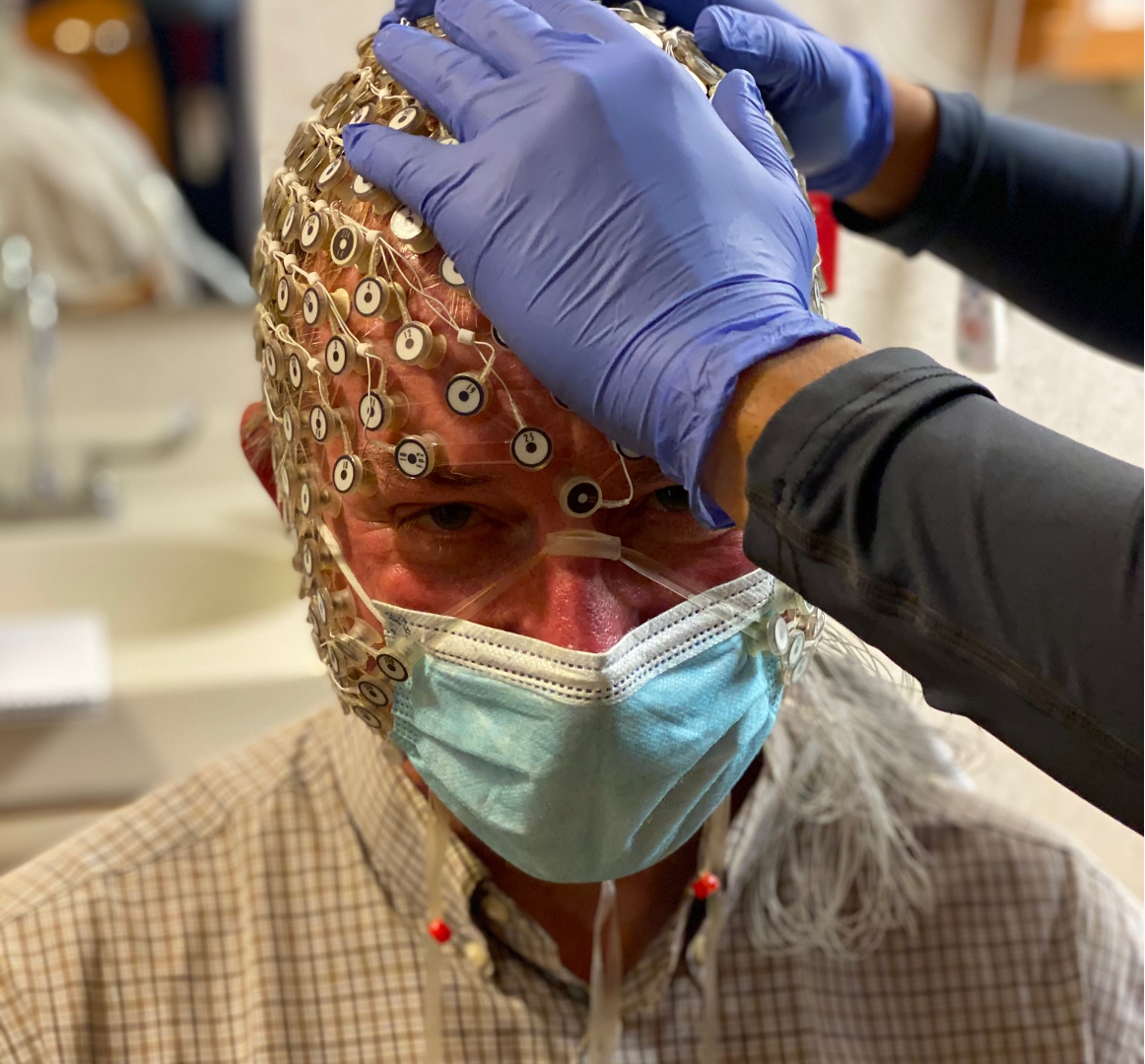

Ketamine can cause sedation. It does cause a sensation that people often refer to as dissociation, where they feel like they’re sort of floating or outside of their body. At higher doses, some people describe this as psychedelic. For those reasons, it definitely needs to be administered under close supervision. We don’t want folks just taking it and then operating heavy machinery, for example. … And I would note that for folks who get that dose wrong, there is a risk of coma and even death. It’s not a compound that should be treated lightly or as if it has no significant risks.

RF: How do you feel about concerns that this treatment is not an FDA-approved use of this drug?

CW: Like other health care decisions, getting a first and second opinion and helping yourself understand how well the clinicians understand the medications they’re working with is really important. I would say it’s especially important in the case of what would be called off-label use.

Regarding the FDA approval, I want to point out that off-label use is not really outside of the norm in psychiatry … But it does create one less layer of oversight on how the product is being used.

So, while it’s not FDA-approved for that (treatment), it’s not like there’s no evidence base or this is just completely made up. There is certainly good reason for folks to have made this next step.

RF: Are you hopeful for success stories with this kind of treatment?

CW: Very hopeful. I think ketamine is the first wave of the next layer of investigations for psychedelic assisted therapies in general. There is still a lot more to learn, but the stories where people are really having those life-changing moments and able to reengage and live the life that they want to are truly incredible. Not everybody is going to be a success, but it’s amazing to see those that are.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, call or text the three-digit suicide and crisis lifeline at 988. Resources are available online here.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.