Over the roughly three decades that Jason Weber worked as a police officer in Fox Crossing, he encountered a fair share of delicate situations. One such encounter involved a man running shirtless through other people’s backyards and acting erratically. When Weber got a dispatch call detailing the incident, he called in support from emergency medical services right away.

“You’ve gotta be kind of quick in your thinking, and to be able to react and get them into custody,” he said.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Weber understood, judging by the symptoms, that he was dealing with what’s described in law enforcement circles as an Emotionally Disturbed Person, or “EDP.” This term refers to individuals dealing with severe emotional and/or mental problems, which also can be accompanied by bizarre and erratic behaviors.

Police are often the first responders on the scene in situations like the one Weber faced. But when it comes to dealing with emotionally disturbed persons, there’s no standardized procedure to rely on, he explained.

Weber said when it comes down to a difficult situation, the most important aspects of managing and de-escalating it are fast action and communication between different first responders.

Since EMS providers and police officers have inherently different jobs, Weber said it’s important all groups know how to work together to successfully deescalate a situation involving an emotionally disturbed person. He cited the 2015 Trestle Trail bridge shooting in Menasha as an example of successful cooperation between agencies that was able to “save precious minutes” at the time.

“We need to train together and we need to work together,” he said. “When it comes down to it, you’re really one big team.”

Weber is now the public safety training coordinator at Northeastern Technical College in Green Bay, where he works to coordinate training for police officers, firefighters and EMS providers already working in their respective fields. Weber explained that the college has two live use-of-force simulators that use videos and special tool belts to train individuals for various types of situations. These simulators can create 500 different scenarios ranging from routine traffic stops to an active shooter.

During a simulation, Weber explained the instructors can control the outcome of the situation based on how an individual responds, for better or worse.

“We’re teaching them how to react,” he said.

Training for these situations can also be done with live role players, Weber explained. These live scenes are often conducted with the help and training from a Crisis Intervention Team.

In Wisconsin, Crisis Intervention Team training is available through the state’s National Alliance on Mental Illness chapter. These teams are outside groups who typically work with law enforcement, mental health providers and other community stakeholders, NAMI Wisconsin associate director Chrisanna Manders wrote in an email to WisContext. Team training consists of a 40-hour program designed to help improve the outcomes of police interactions with people living with mental illnesses.

“By bringing together these key community partners, various areas are represented and reached, meeting the the unique needs of individual communities,” she said.

Responding to excited delirium

A condition defined as “excited delirium” is generally accepted by the law enforcement and EMS communities, but it is not without controversy. The term gained popularity in the 1980s to describe patients suffering from cocaine overdoses, and in recent decades, it’s often been cited as the cause of death in dozens of officer-involved incidents around the United States.

Identifying excited delirium is a relatively standard process, said Dillon Gavinski, director of Madison College’s emergency medical services program. Symptoms often include agitation, delirium, high body temperature, and in some cases, extreme strength. Calming the individual and lowering their body temperature is a top priority for EMS providers.

Addressing an individual dealing with excited delirium from an emergency medical standpoint is similar to that of a police officer’s, said Gavinski. He explained that recognizing the symptoms of excited delirium is critical to addressing a situation involving a person experiencing the condition.

Learning about the symptoms, medical history and overview of excited delirium is a required “core topic” of Crisis Intervention Team training in Wisconsin, explained Chrisanna Manders.

This training is standardized across the state and regulated by the state’s CIT Advisory Committee and organized by NAMI Wisconsin. The committee, which formed in 2016, is composed of law enforcement officers, mental health advocates, behavioral health specialists and those with experience with mental health and Crisis Intervention Team practices.

When it comes to addressing cases identified as excited delirium in the field, despite there being no state-government-standardized process, there are many commonalities in training across law enforcement, emergency response and medical organizations in Wisconsin.

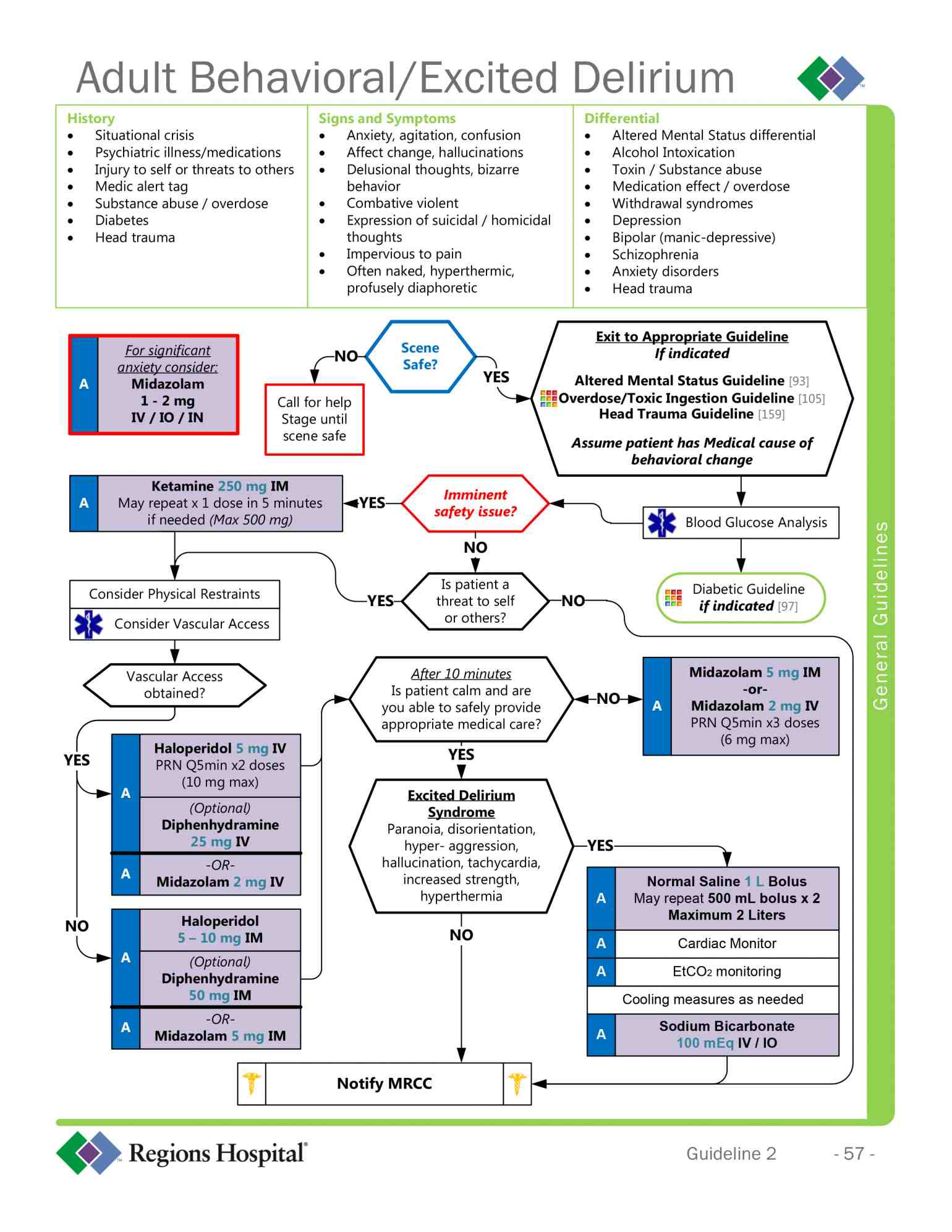

WisContext reviewed treatment protocols published online since 2016 by the Oshkosh Fire Department, Dane County EMS, University of Wisconsin-Madison Police Department and Regions Hospital facilities and partners in western Wisconsin that address how patients identified with being in a state of excited delirium should be treated.

Many recommend the use of ketamine, an anesthetic used for humans and animals that is abused recreationally, as an appropriate medication to sedate a person with excited delirium.

However, there are also distinct differences among these protocols. Dane County EMS notes Haloperidol as an alternative to ketamine if a person is in a “moderate” state of agitation versus a “severe” state. The Regions Hospital system also mentions Haloperidol, though only as an option after the use of ketamine.

Nearly all of those protocols note that an individual’s breathing and activity levels should be monitored. In its training guidelines, the UW-Madison Police Department even goes as far to indicate that “the cessation of struggling should be viewed as ominous and prompt re-evaluation should occur.”

These organizations also note the use and importance of soft restraints, rather than traditional handcuffs or other restraints in their training protocols. The UW-Madison police notes in its training materials that the person should be placed in a “non-prone positions” as soon as possible.

Most protocols stress the importance of creating and maintaining a calm environment as to not further agitate a person in distress.

Many of these organizations also underscore the importance of having the proper first responders on the scene to being with and ensuring their own safety and the safety of other people nearby. In its guidelines, the UW-Madison police state that excited delirium is a medical emergency and should be treated as such. It notes that drugs may be contributing to such an individual’s condition, and that EMS should be called right away.

Public safety training coordinator Jason Weber likewise stressed the importance of EMS when it comes to training police officers.

“The most important (thing) from our (side) is to have EMS on scene, and it’s working hand in hand,” he said. “It’s building those relationships ahead of time between first responders.”

Examining The Emergency Medical Playbook For Treating Excited Delirium was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.