Wisconsin children have been back to school for several weeks, and already the highly contagious delta variant of the coronavirus has made its presence known. Some school districts started reporting positive cases their first week back, and some schools have temporarily shut down or quarantined entire classes after hitting a critical mass of sick teachers and students.

The delta variant is far more contagious than the coronavirus that was circulating this time last fall, which has led to a new spike in infections among kids that’s almost as high as the November 2020 spike before COVID-19 vaccines were available — and even higher for some age groups and in some areas.

Still, kids’ risk of severe disease is much lower than that of adults, and doesn’t seem to be any higher with delta than it was with earlier iterations of the virus, said Dr. Greg DeMuri, a pediatrician at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“It’s just that there are more cases, so a small percentage of a large number is still a significant number,” he said.

As a result, Wisconsin and the rest of the country have seen more children hospitalized, more children in ICUs, and more cases of multi-system inflammatory disease, a rare but serious set of symptoms linked to COVID-19 in some children.

Fewer than 2 percent of COVID-19 cases in children result in hospitalization. According to data from the Department of Health Services, there have been three deaths in Wisconsin of people age 19 and under from COVID-19, out of nearly 8,000 deaths over the course of the pandemic.

While that number is low, DeMuri noted that a typical year brings about 60 to 100 child deaths from the flu nationwide. There have been more than 600 pediatric deaths from COVID-19.

“If you’re only looking at your own child, the safety of yourself and your child, there’s a relatively low chance your kid’s going to die or get severely ill,” he said. “But when it comes to your child, usually we get really upset about very low-risk events.”

Darren Rausch, director of the Greenfield Health Department, said it’s also very possible to aim for zero deaths in children — those 12 and up can be vaccinated, those under 12 are protected when all the adults around them are vaccinated, and recent studies have shown that masking is highly effective in preventing the spread of even the more contagious delta variant.

“While those numbers of deaths are small, any reported death in a Wisconsin school child is tragic and it is preventable,” he said in a briefing last week. “I know many people minimize the severity of COVID-19 in children, and they use that as a rationale for not making decisions for kids to wear masks or kid to be vaccinated, but I’m here today to tell you that the risk is real in kids.”

The risk of severe or life-threatening cases of COVID-19 is much higher in kids with underlying conditions that put them at higher risk for illness more generally, and for COVID-19 complications specifically — so the way families weigh the risk to a child with severe asthma or an autoimmune disease, for example, is different from how they weigh the risk to a child without factors that would make more severe illness more likely.

Kids’ comparatively low risk of severe disease also doesn’t exist in a vacuum. DeMuri noted that even if families do everything right after a child tests positive by keeping them home and quarantining, kids can be contagious for two days before showing any symptoms and can spread the disease to vulnerable adults during that time. On average, people infected by the delta variant spread it to about seven other people.

“Who of those people is going to be vulnerable and going to die?” he said. “They might spread it to a vulnerable teacher, or the janitor, or a bus driver who’s immunocompromised.”

Wisconsin has also seen a surge in respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, which emerged much earlier this year than usual. Experts have also warned that the flu could be particularly severe this year, and the flu shot less effective, which altogether could mean an even bigger strain on an already overburdened pediatric medical system, said Dr. Amy Falk, a pediatrician in Wisconsin Rapids.

“The ramifications of a kid getting COVID is more than just, is my kid going to end up in a hospital or worse — it’s kind of, can we even get appendicitis now? Can we even take care of you, can you find a clinic spot if you’re worried?” she said.

In her case, Falk said the answer is frequently “no” — she said her practice has been triple-booked. Worries about COVID-19, as well as its strain on the hospital system, have also led some families to put off well-child visits or other preventive care, including vaccinations.

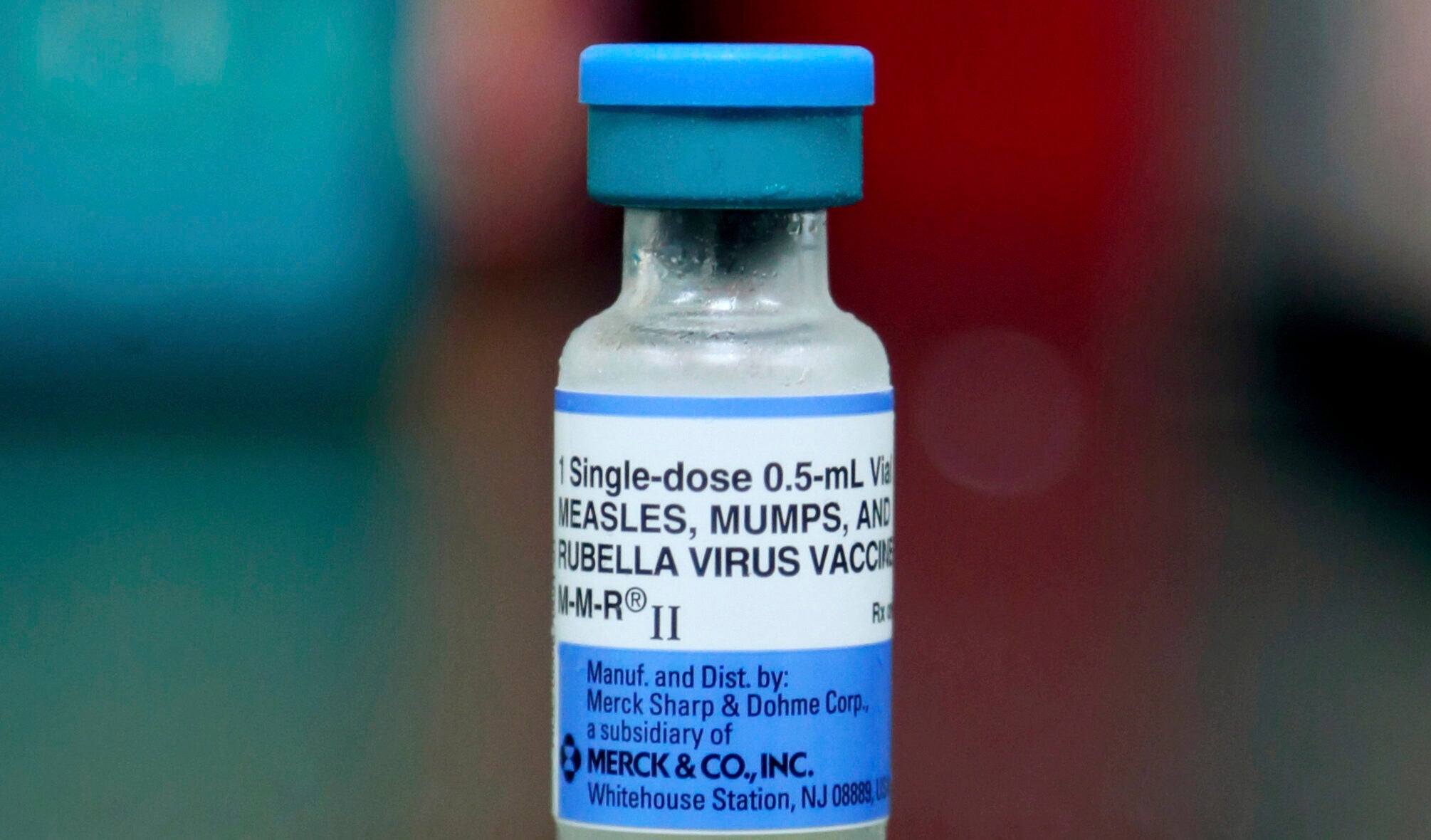

“Fewer people in Wisconsin got their routine vaccinations in 2020 compared to the average number vaccinated from 2015 to 2019, with children 6 and under seeing the biggest drop. Falk said she worries that could, in the long term, lead to clusters of vaccine-preventable diseases that would further stress the healthcare system.

There are also the practical and financial concerns of kids contracting or coming into contact with COVID-19, she said.

“It’s a huge burden for families to have to quarantine. Let’s say you go to Girl Scouts, and you end up having to quarantine,” she said. “That’s 10 days that the kid can’t be in school, two weeks in some areas, and to do that over and over again is burdensome financially for the family.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.