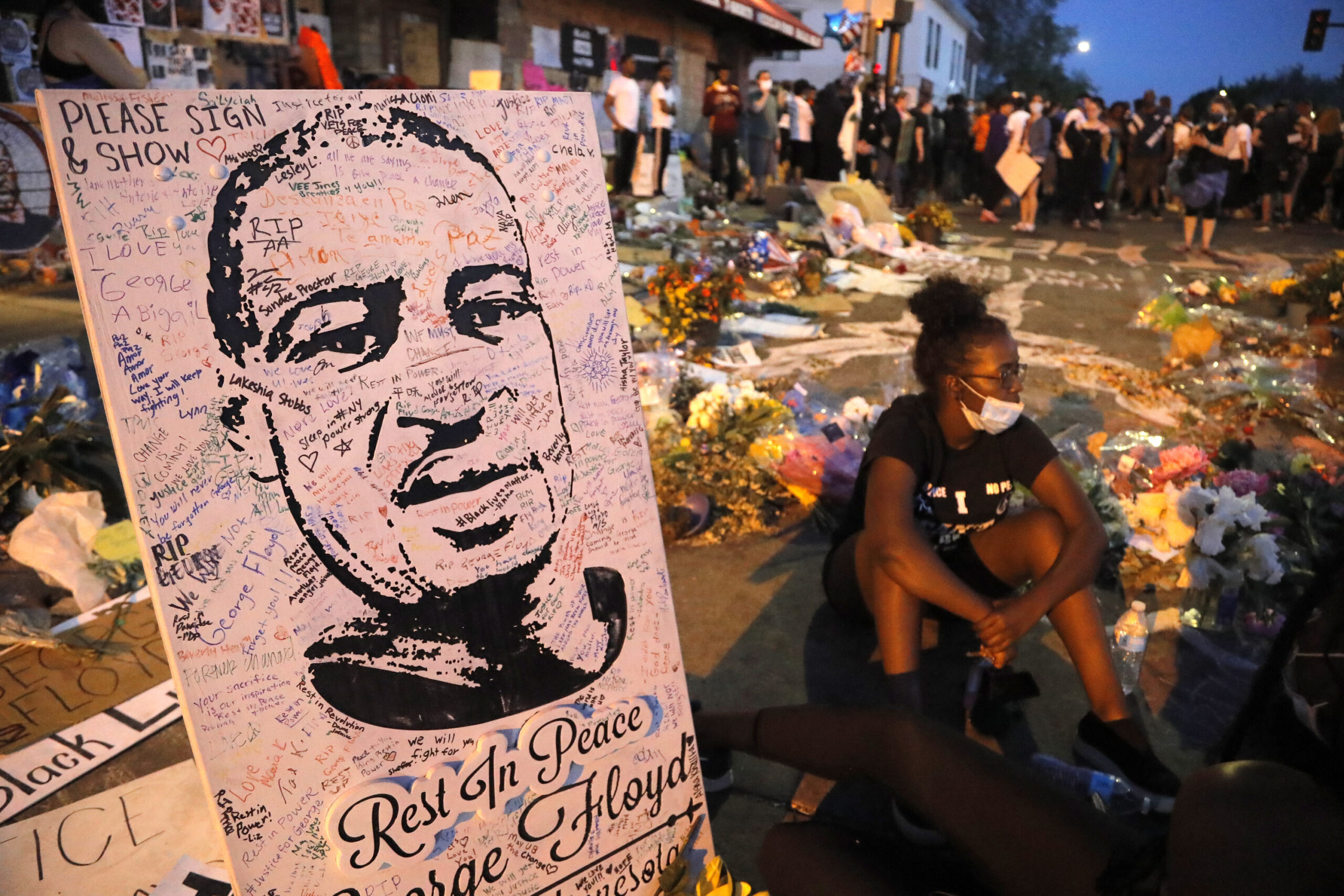

The arrest and subsequent death of Minneapolis man George Floyd — who died in police custody after ex-officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes — has sparked outrage across the globe. For more than a week, people across the nation have come together in both peaceful and violent protests, calling for an end to racism and police brutality.

Several Wisconsin police chiefs have condemned Chauvin’s actions, who has since been charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Chauvin faces up to 25 years for the murder charge and up to 10 years for the manslaughter charge.

Wausau Police Chief Ben Bliven posted to the department’s Facebook page three days after the incident, responding to what he said were numerous requests for a response from the department. He wrote that although he’d seen a lot of “use-of-force” videos in his career, he couldn’t make sense of what he saw in the video of Floyd’s arrest.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I love the policing profession. I love our country. I love my community,” he wrote. “And what I saw in that video is against everything that I stand for in this profession, everything that our nation represents.”

Both Bliven and Green Bay Police Chief Andrew Smith called the Minneapolis police officers’ actions murder, and said that building relationships between police officers and the communities they serve is one of the most important steps to take in times of crisis.

Selika Ducksworth-Lawton agreed, and said it’s time for officers to get out of their cars and make those connections. Ducksworth-Lawton is a professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire and helped organize a recent demonstration in Eau Claire protesting Floyd’s death.

“The police communities have to build relationships with the community — not just with a few leaders,” she said, adding there needs to be some delineation between protestors and those with intent to harm. “What they need to understand is the protestors who aren’t armed and the looters who are armed are two different groups.”

Ducksworth-Lawton, who’s black, said black people want to be seen as individuals and not as criminals.

“Just as police don’t want to all be seen as corrupt, black people don’t want to all be seen as criminals, and protestors want the police to protect them,” she said.

Bliven said their department communicates regularly about ways to de-escalate situations. It also reviews all instances where force is used. More generally, he said the department focuses on core values like professionalism, accountability, integrity and respect.

That being said, Bliven said the tools an officer has could be wielded inappropriately, so it comes down to the character of the officer called to the scene and how well he or she has been trained to de-escalate situations.

“It’s a heart issue. It’s a character issue. It’s a relationship with our community issue,” he said.

Bliven said it’s also important that law enforcement agencies make sure their departments reflect the communities they serve.

Smith, from Green Bay, knows firsthand what happens when the police force doesn’t reflect the community it represents. He worked for the Los Angeles Police Department for 27 years, including during the 1992 Los Angeles riots when the city’s residents raged over Rodney King’s beating at the hands of police officers and the subsequent acquittals of three of them.

“We felt like we were an occupying army,” Smith said. “It was us versus them.”

Like the events in LA almost 30 years ago, Floyd’s death and subsequent protests have mobilized and outraged people across the United States. Barron Police Chief Joe Vierkandt watched the video of Floyd’s arrest twice. He thought about what he would have done if he was in that situation and imagined communicating with Floyd and listening to him.

“We talk about de-escalation, and that’s something that we have expectations for every single one of our officers to possess,” he said.

Other departments around the state took to Facebook, Twitter and other social media platforms to add their voices to the chorus of officers labeling Chauvin’s actions as “horrific.” Matt Kelm, police chief in Chippewa Falls, posted to Facebook to announce his department is “united in our condemnation of the action, and inaction, displayed in the video.”

In Kenosha, Police Chief Daniel Miskinis said in a community message that the practice used by Chauvin of kneeling on Floyd’s neck for a length of time is not taught to officers in Kenosha, nor is it used.

Vierkandt, of Barron, said Chauvin’s actions reminded him of an outdated method of “hog-tying” uncooperative subjects by binding their hands and feet behind their necks. This type of restraint has been banned by police departments over concerns it leads to asphyxiation, Vierkandt said.

“I’ve been in law enforcement for 19 years and I’ve never seen another officer place his knee on another human’s neck,” he said.

Vierkandt said listening is one of the most important tools an officer can use in these situations, especially when working with a public that is distraught and frustrated. That’s been evidenced in reports of looting, vandalism and destruction of buildings that some people support as necessary actions to prompt change and others decry as senseless.

Barron was subject to some of that vandalism Monday. Three suspects were spotted by an officer making rounds at 1 a.m. on Monday at a main pavilion in Anderson Park. The words “BLM” and “No justice no peace” were spray-painted onto the side of one of the walls.

While he doesn’t believe vandalism will solve the systemic racial divide, Vierkandt said he is open to finding new ways to connect with the community at large and address these issues.

Ducksworth-Lawton said addressing those issues needs to involve training and de-escalation. And as for white people, she said they need to step up and help out.

“We need the good white people to help us, and that is, I think, the most important thing,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.