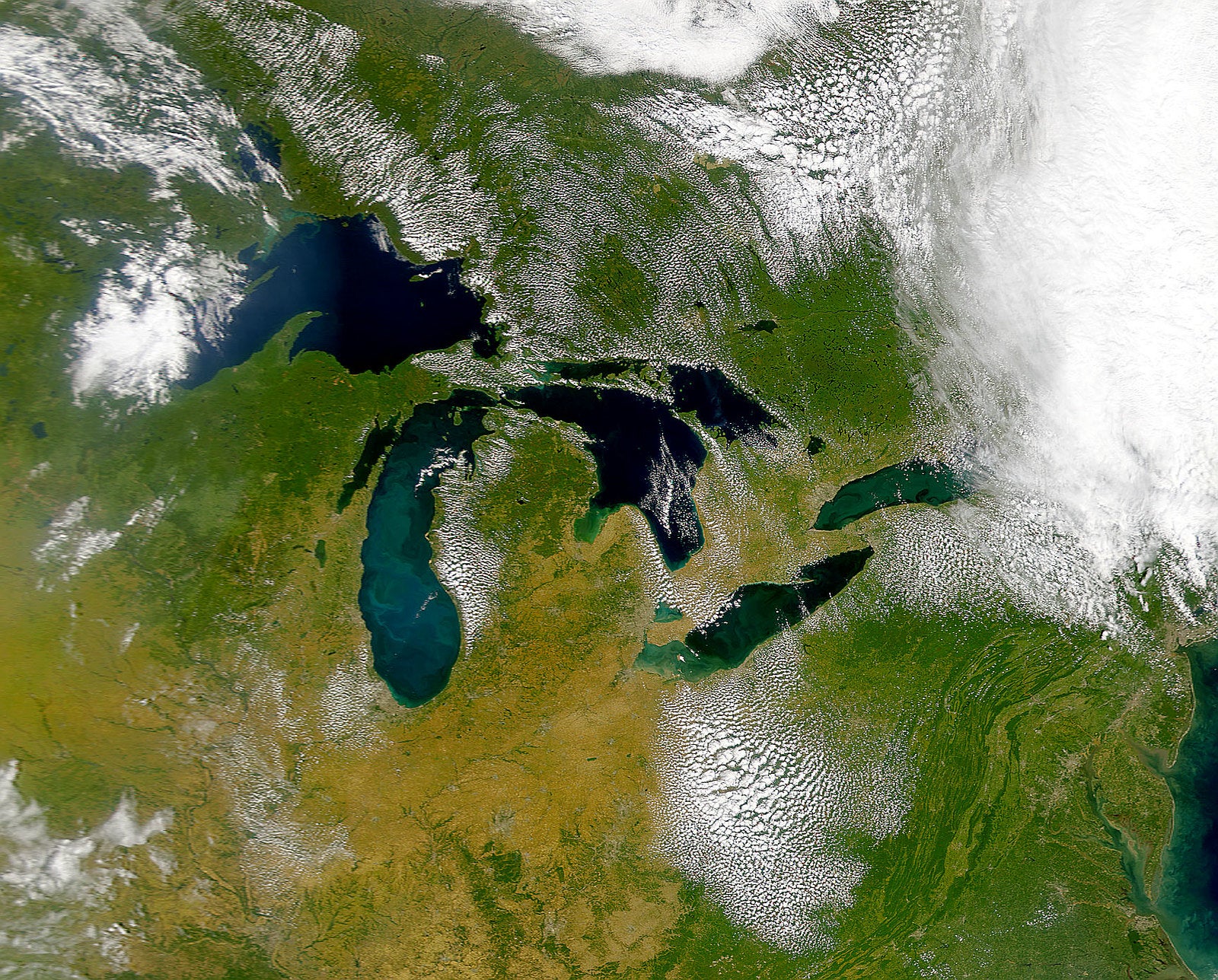

Winter is historically when water levels recede in the Great Lakes. But last month, Lake Michigan broke a 33-year-old record high, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Damage caused by flooding from Lake Michigan prompted state and local authorities in late January to declare a state of emergency. Last week, the Corps forecasted that high water levels were “expected to persist for at least the next six months.”

In an interview on WPR’s “The Morning Show,” hydrologist Drew Gronewold said erratic water levels in the Great Lakes may be increasingly common with climate change. Gronewold, an associate professor at the University of Michigan, discussed how communities are responding with host Kate Archer Kent.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: How significant is the new record high in January?

Drew Gronewold: It’s significant for a lot of different reasons. January and February are usually the time of the year when water levels are at their seasonal low and then they typically rise through the spring and reach a peak in June. So the fact that we’re breaking a record for the month of January has really two important implications. One is that it’s setting things up for above average water level conditions for the next several months. But it also suggests that there’s some broader things going on in terms of the hydrologic cycle and possible shifts in the magnitude and the timing of snowmelt across the region.

KAK: It has been warmer and wetter than usual. How is that contributing to what you’re seeing in these water levels?

DG: If we look regionally or even on a continental scale, a warmer atmosphere is holding more moisture and bringing more rain to the Great Lakes region. The past decade was the wettest in recorded history for the United States, and much of that record was due to precipitation in the upper Midwest and the Great Lakes region. So in general, more precipitation is coming to this region.

But then also warmer winters and even winters with more erratic temperatures tend to lead to different snowmelt patterns than we’re used to. For example, in a typical historical winter, we might imagine snow would accumulate throughout the winter and then melts primarily in February, March and April. But with erratic temperatures throughout the winter, that snow can melt earlier and even some of the precipitation might fall as rain rather than snow. As a consequence, water levels might stay steady and even start rising earlier than they normally would.

KAK: As you look at the effects today on shoreline communities, what are you seeing?

DG: A lot of the problems that we see right now have to do with flooding of homes, erosion of sand dunes. And unfortunately for homes and infrastructure that are placed near steep sandy dunes or bluffs, some of these houses are actually falling in the water. And there are areas right now where municipal infrastructure, not just roads, but even wastewater treatment facilities are being affected by high water. And this is really a major problem.

KAK: How have Great Lakes communities responded to the damage caused by high lake levels?

DG: There are places where folks are putting up remedial measures. They’re putting up sandbags and things like that on a very short-term timescale. On a slightly longer time scale, though, there are a lot of discussions about things like hardening shorelines or putting up more stone along shorelines to prevent erosion. And there’s some problems associated with that, even though it’s viewed sometimes as a common solution, in part because those solutions can lead to major changes in near circulation patterns and also the movement of sand and sediment that form beaches and contribute to the shoreline.

KAK: What kind of significant policy changes may be needed to adjust for climate change?

DG: I think the biggest policy change for the Great Lakes in terms of the conversation we’re having right now has to do with coastal infrastructure and zoning requirements. We need to have some very important discussions about how comfortable we are with water level oscillations along the shoreline and what risks we’re going to take in terms of allowing people to build homes and infrastructure along that shoreline.

Not everybody has the resources to simply up and move a home or sell a home. I think that’s one of the most important policy decisions we have to make right now about what we allow people to do in that shoreline and whether some of their shoreline needs to be set aside for other purposes.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.