Wisconsinites are adapting to life under the cloud of COVID-19, and for a growing group that means getting into the habit of covering up with a face mask when they venture from their homes.

Indeed, face masks may be spring 2020’s most en vogue apparel, though the burgeoning trend began not on a fashion runway but with a dryly worded recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The CDC’s recommendation that Americans wear non-medical “cloth face coverings” in public places such as grocery stores and pharmacies came on April 3, after weeks of growing speculation it might happen. The move came as a debate builds among health experts in the United States and around the world on the role of face masks in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Advocates for using face masks have cited the slower progression of outbreaks in places where their use in public is deeply ingrained, such as in Hong Kong and South Korea, though evidence directly linking their use in public to reduced transmission of respiratory disease is lacking. Some have also argued that wearing masks could still help slow the spread of COVID-19 by reinforcing social norms and appropriate hygiene practices that can help limit transmission, especially if individuals who don’t know they are infected wear one.

And yet other public health authorities, including at the World Health Organization, have feared any new guidance encouraging the broad use of face masks, even if it explicitly emphasized preserving medical-grade masks for healthcare settings, would inevitably exacerbate acute shortages hospitals are feeling worldwide. More than a week after the CDC changed its stance on the matter, the WHO maintains its guidance that healthy people should only wear a mask if they are caring for someone with COVID-19. Many medical professionals and public health experts in the U.S., including in Wisconsin, feel the same way.

For its part, the CDC issued carefully worded language that provided individuals who wished to wear a face mask with instructions for crafting their own mask out of household materials.

The recommendation attempted to strike a balance between concerns on each side of the mask question. As such, it amounted to somewhat of an about-face for the agency, whose prior guidance explicitly did not recommend the public use of masks of any type among healthy individuals in response to COVID-19. In Wisconsin, health officials conformed with the CDC’s prior stance when WisContext first explored this issue in February.

Public health guidance aside, many people in Wisconsin and elsewhere have decided for themselves whether or not to wear a mask in public, perhaps driven in part by their increasingly ubiquitous presence in the news and on social media.

No matter how they came to their decision, many did not wait for the CDC’s new stance, which came more than two months after the disease was first diagnosed on American soil. What changed over this period that would have prompted such a fierce debate among public health experts and ultimately led to the new guidance?

Shifting norms, limited evidence

In making its recommendation, the CDC acknowledged a growing body of evidence that many people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, may show little or no symptoms even while carrying a significant amount of the virus in their systems. The evidence, including the CDC’s own examination of a cluster of cases in King County, Washington, has added weight to concerns that asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic individuals may be an unwitting and significant vector of the disease.

“That may have been the tipping point for this change,” said Dr. Nasia Safdar, an infectious diseases physician and chief medical officer for infection control at UW Health in Madison.

Safdar pointed out that scientific evidence that would link the widespread use of face masks to slower transmission of COVID-19 remains elusive.

“The data supporting it hasn’t really changed all that much,” she said.

What has changed, in Safdar’s view, besides a firmer understanding of asymptomatic infection, is Americans’ attitudes toward wearing face masks in public.

“The decisions that are being made are being swayed by momentum, by public opinion and by what others have done, in Asia, for instance, where there’s long been this culture of wearing masks in public,” Safdar said.

Wisconsin’s state epidemiologist of communicable diseases Dr. Ryan Westergaard shared that view.

“I think two things happened,” said Westergaard. “One is that there’s sort of a general public acceptance [of wearing face masks]. Initially it was sort of at odds with our cultural norms.”

The other shift, according to Westergaard, is the public health view that wearing a face mask could possibly help reduce the impact of lax etiquette among people who fail to properly cover their sneezes and coughs, especially if they are carrying the virus without realizing it. To that end, wearing a face mask in public is less about personal protection and more about protecting the community.

“I don’t know the degree to which the public sees that distinction,” Westergaard said.

At the same time, any protective impact of wearing face masks in public could easily be negated by their improper use, which is something Safdar worries a lot about. It only takes one sneeze or cough to potentially soil a cloth mask with infectious particles, meaning even a minor mask adjustment could risk contaminating a wearer’s fingers and subsequently anything they touch.

“It just seems fraught with potential for contamination,” Safdar said.

Concerns over medical supplies persist

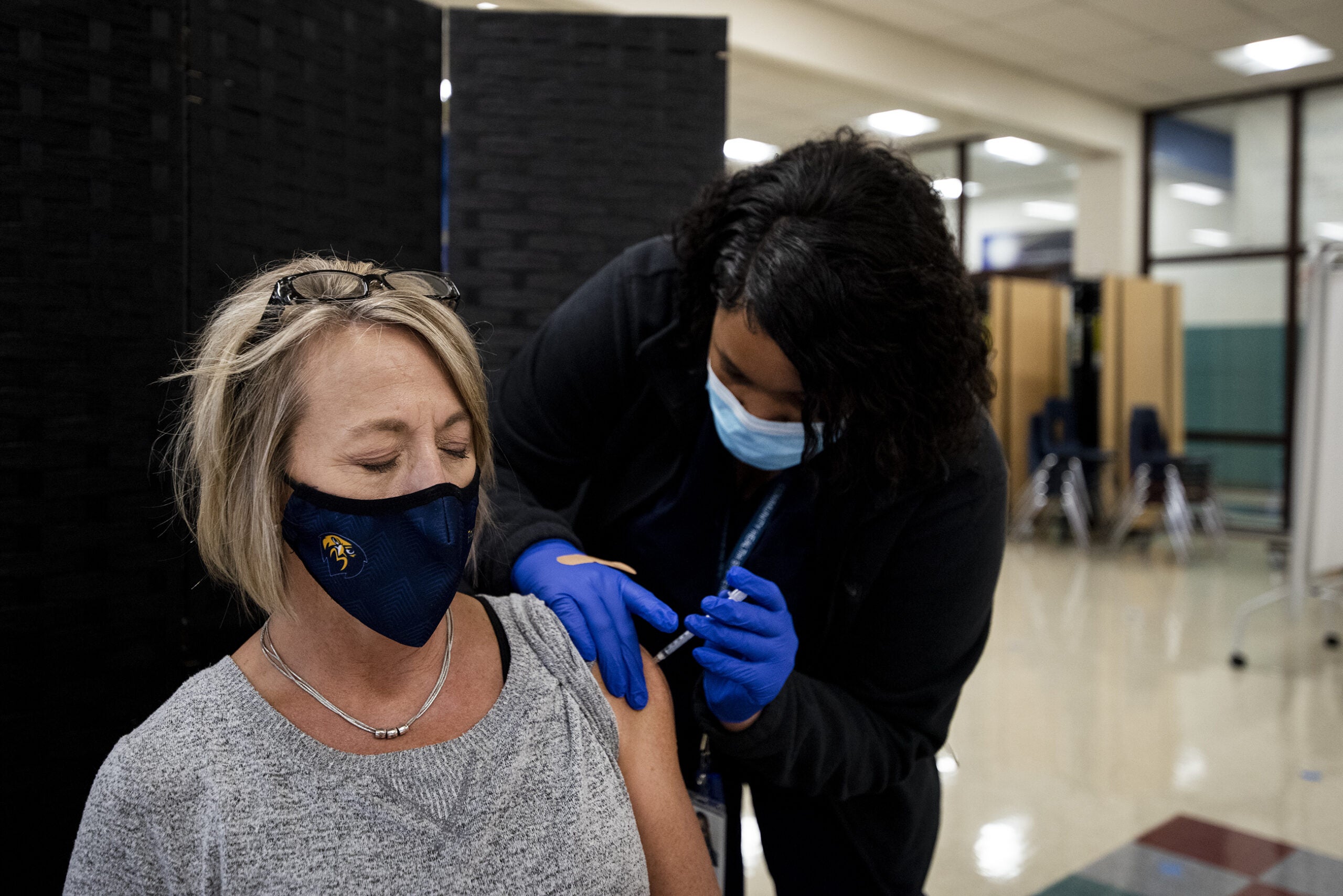

Public health officials remain worried about the potential diversion of personal protective equipment like medical-grade surgical masks and N95 respirators as more people take up wearing face masks in public. This equipment is crucial for protecting healthcare workers while they test and treat symptomatic patients, and many workers in Wisconsin, from nurses in urban hospitals to rural EMTs, remain critically short of it.

Westergaard said personal protective equipment continues to be Wisconsin’s “highest need” in its response to COVID-19. The state’s needs remain so acute that it has set up a donation and exchange system to facilitate the acquisition of personal protective equipment and other medical supplies.

The CDC’s face mask guidance is clearly crafted to encourage the use of homemade or purchased cloth masks and explicitly calls for preserving personal protective equipment like N95 respirators and surgical masks for healthcare settings. But numerous images of voters and poll workers wearing medical-grade gear during Wisconsin’s April 7 election signaled that many people may not be receptive to this message as it gets drowned out by fears over the contagion.

Both Westergaard and Safdar said they don’t blame anybody for wearing medical masks at polling stations, especially if that’s what election officials gave them, or if it was what they had on hand. Safdar instead reserved her judgment for state officials who allowed in-person voting to take place in the midst of a pandemic, a situation she said “wasn’t a great idea.”

“I think you send a mixed message to people where you’re telling healthcare workers to reuse their PPE when they’re taking care of actively sick patients, but yet, in the public, you’re seeing this waste of PPE,” Safdar said. “It’s a shame.”

A personal decision

Mixed messages from elected officials can make the decision to wear a face mask — and choosing which type to wear — a fraught one for Wisconsinites who are still figuring out how they can best protect themselves and their communities.

Unlike in a growing number of municipalities such as Washington D.C, Miami and Los Angeles, deciding whether to wear a mask or other face covering in public remains a personal decision in Wisconsin, and residents are choosing to use them for a variety of reasons.

Ruth King lives near Spooner in rural Washburn County, which reported its first confirmed COVID-19 infection on April 13. A stormwater specialist with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, King questions whether there is clear scientific evidence supporting the use of face masks in public. Still, she buys groceries for her elderly mother and generally heeds advice from the CDC, King said, and she wants to do her part to minimize the chance she or members of her family could catch the highly contagious disease.

King has also noticed more people wearing masks as they shop for food and supplies at Spooner’s lone grocery store since the CDC shifted its guidance.

“When a lot of people are wearing them, you feel the peer pressure to wear them yourself,” King said.

Across the state in Green Bay, Carl Hujet is concerned that a recently diagnosed heart condition puts him at a higher risk for complications should he come down with COVID-19. A neighbor recently gave Hujet a hand-sewn mask, and he fashioned another with supplies from home. Hujet said the CDC’s new guidance prompted him to transition from wearing a mask in public only sometimes to doing so religiously, whether he’s at the grocery store, doctor’s office or a gas station.

Hujet has read that wearing a mask is more about protecting others in case one is an asymptomatic carrier, but he also feels a greater sense of personal security with one on.

“I don’t want to kill anybody, and I don’t want to be killed,” Hujet said.

Meanwhile, Ann Gainey of Wind Lake in exurban Milwaukee has considered it prudent to wear a face mask in public since the disease began spreading globally after the initial outbreak in China, which prominently featured imagery of Chinese citizens and leaders donning masks.

A retired nurse who spent four decades caring for nursing home residents and ICU patients, Gainey said she was frustrated with the CDC for waiting so long to shift its guidance on the use of face masks in public.

“I was an advocate of face masks from the get-go,” said Gainey, who said she understood the CDC was likely worried about runs on medical personal protective equipment. Still, as its new, carefully worded guidance demonstrates, there are other face covering options for the public.

To that end, Gainey has sewn and sent more than 150 cloth masks to friends and family around the nation since the outbreak began.

“It upset me that people weren’t being encouraged more to wear face masks,” she said.

In Madison, Sam Million-Weaver said he also felt an urge to wear a face mask prior to the CDC’s new stance, but a lack of clear guidance made him feel as though there wasn’t social permission to do so.

“If no one’s doing it, you don’t want to be the one weird guy wearing a mask,” said Million-Weaver, who is a medical writer for a medical science organization. He said that since the CDC changed its mask guidance he’s noticed many more people wearing face coverings in public at places like his neighborhood grocery store. Still, Million-Weaver is concerned that the federal government’s messaging on the matter remains confused.

“It would be helpful if our government could send a unified message,” he said, taking issue with President Donald Trump’s refusal to wear a mask.

“A lot more people would be following the good public health example if our elected leadership was setting a good public health example,” he said.

Mask demand spikes

No matter the messages coming from the federal government, many Wisconsinites are taking up the use — and creation — of face masks. That’s according to organizers of a statewide volunteer effort to sew and distribute cloth masks who have been inundated with requests since the CDC shifted its guidance.

The Wisconsin Face Mask Warriors is a growing network of volunteers with local chapters around the state, such as one in Green Bay. In late March, members began producing cloth face masks for frontline workers in essential sectors, including nursing homes, grocery stores and pharmacies.

The group produces masks that fall in line with the CDC’s recommendations — multiple layers of washable cloth that fit tightly over the nose and mouth and have ear straps. The cotton masks can be washed repeatedly and are compatible with autoclave systems that sterilize materials under high pressure and temperature.

The group’s ranks have quickly grown to more than 4,000 volunteers around the state, according to organizers Dena Bennett of New London and Jenni Cardell of Madison. But demand for their masks has also exploded, both from facilities lacking personal protective equipment — including medical facilities — and from a growing number of individuals seeking the masks for personal use.

“We have just been bombarded with requests. It’s just crazy,” said Bennett.

The group does not deny personal requests, Bennett said, but prioritizes those from institutions and frontline workers.

Requests range from a handful of masks to huge shipments, noted Cardell.

“Just in the last 15 minutes we had a single request come through … from a medical facility, and they were asking for 15,000 masks,” Cardell said in an interview on April 9.

Such demand speaks both to a public desire to minimize transmission and to the ongoing trouble Wisconsin’s health systems face as they seek to secure protective equipment for frontline workers confronting COVID-19.

Emphasizing proven strategies

The goal of limiting the spread of COVID-19 is why public health officials like Ryan Westergaard and Nasia Safdar are underscoring the need to maintain strategies that are proven to slow transmission, chief among them proper handwashing and significant physical distancing.

Several weeks after their implementation in Wisconsin, these measures may have started to slow the rate of new infections in the state — or “flatten the curve” — by mid-April. However, state officials cautioned against declaring an early victory.

Westergaard also emphasized that wearing a face mask must not be considered a stand in for physical distancing or proper hygiene etiquette.

“We don’t want people to wear face coverings at the expense of paying attention to other important infection control measures like hand washing,” he said.

Safdar said the positive effects of physical distancing, including Wisconsin’s stay-at-home order, are apparent at Madison’s University Hospital, where she works.

“We’re definitely seeing a decline in the trajectory [of new infections],” she said. “We’re still seeing a few, but it’s nowhere near as fast and high in volume as we expected when this started out based on what we have seen other cities dealing with. So in the health system, we are seeing an effect of social distancing being done by the public.”

Safdar acknowledged the steep economic costs of the state’s measures, but said she hoped they would remain in effect for some time to come, fearing a resurgence in transmission if distancing were relaxed too much too soon.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.