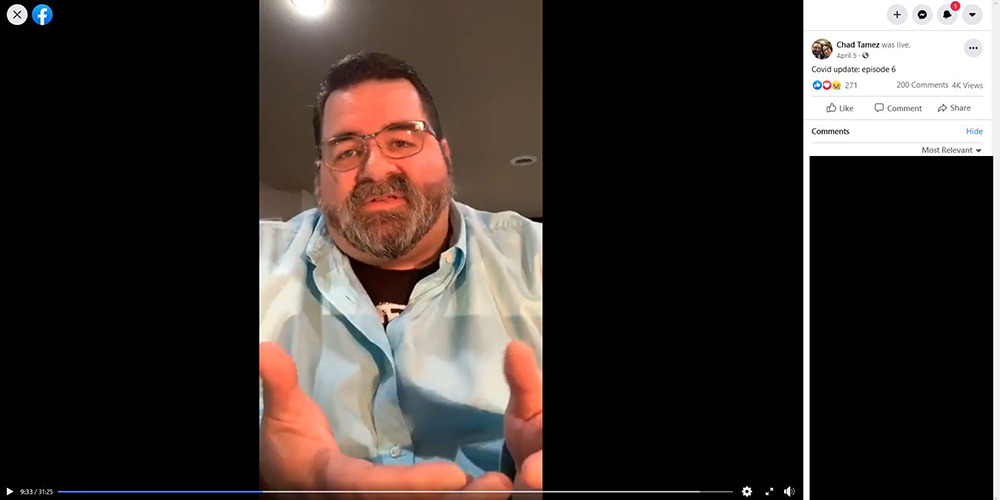

When the coronavirus started spreading around Wisconsin in the spring of 2020, Dr. Chad Tamez hosted Facebook Live sessions to help patients understand what was initially a mysterious new pathogen. A family physician who co-owns a private practice in West Bend, Tamez seized on the power of social media to discuss new medical findings about the coronavirus. But after a few weeks, he stopped hosting the sessions when he realized the pandemic was becoming political.

More than a half-year into a society-upending pandemic, the medical world had expanded its understanding of the COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. Multiple vaccine candidates had reached late-stage trials, and epidemiologists better understood how the virus spreads and attacks the human body. This growing body of knowledge draws on rivers of data about COVID-19 — flowing daily from medical and public health researchers in Wisconsin and worldwide.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But some of Tamez’s patients remain deeply skeptical about the severity of disease, he said, even as the coronavirus infected and killed growing numbers of Wisconsinites in the fall, overwhelming hospitals and prompting the state to open a field hospital to alleviate pressure in crowded COVID-19 wards.

“There’s definitely confusion, and there’s definitely suspicion,” Tamez said.

Fueling those feelings: viral misinformation permeating American life in 2020, Tamez believes, as increasingly large swaths of a polarized populace take their cues from social media.

“I know people who think masking is foolish and think that the numbers are inflated or falsified, or that this is all just going to disappear after the election,” Tamez said.

West Bend sits in one of the most politically conservative parts of Wisconsin, but Tamez said he’s encountered a range of attitudes toward the disease, from obsessive fear to total dismissiveness. Tamez said some of his patients are falling prey to the false information they see on their social media feeds.

“You can tell where people are getting their data, because you hear the same thing over and over,” he said. “And I go, ‘OK, I know where that’s coming from, and I can tell that you’re not looking into the data for yourself. You’re just using whatever someone told you or something you read on Facebook.’”

Wisconsinites have grown weary of the pandemic, relaxing their behaviors and ignoring public health guidance and restrictions to slow the spread of a deadly disease. The result is a public health nightmare: Officials must simultaneously wage war on a pandemic and a parallel “infodemic” of false, misleading and dangerous claims that downplay the seriousness of the disease.

These conspiracy theories, many rooted in misleading interpretations of COVID-19 data and partisan animosity, are stoking suspicion among COVID contrarians and armchair epidemiologists, complicating the already difficult task of doctors and public health officials to encourage mask-wearing, distancing and other ways to slow the virus’ spread. As their exhaustion grows, so does the pandemic’s grip on Wisconsin — in a deadly, fast-churning cycle.

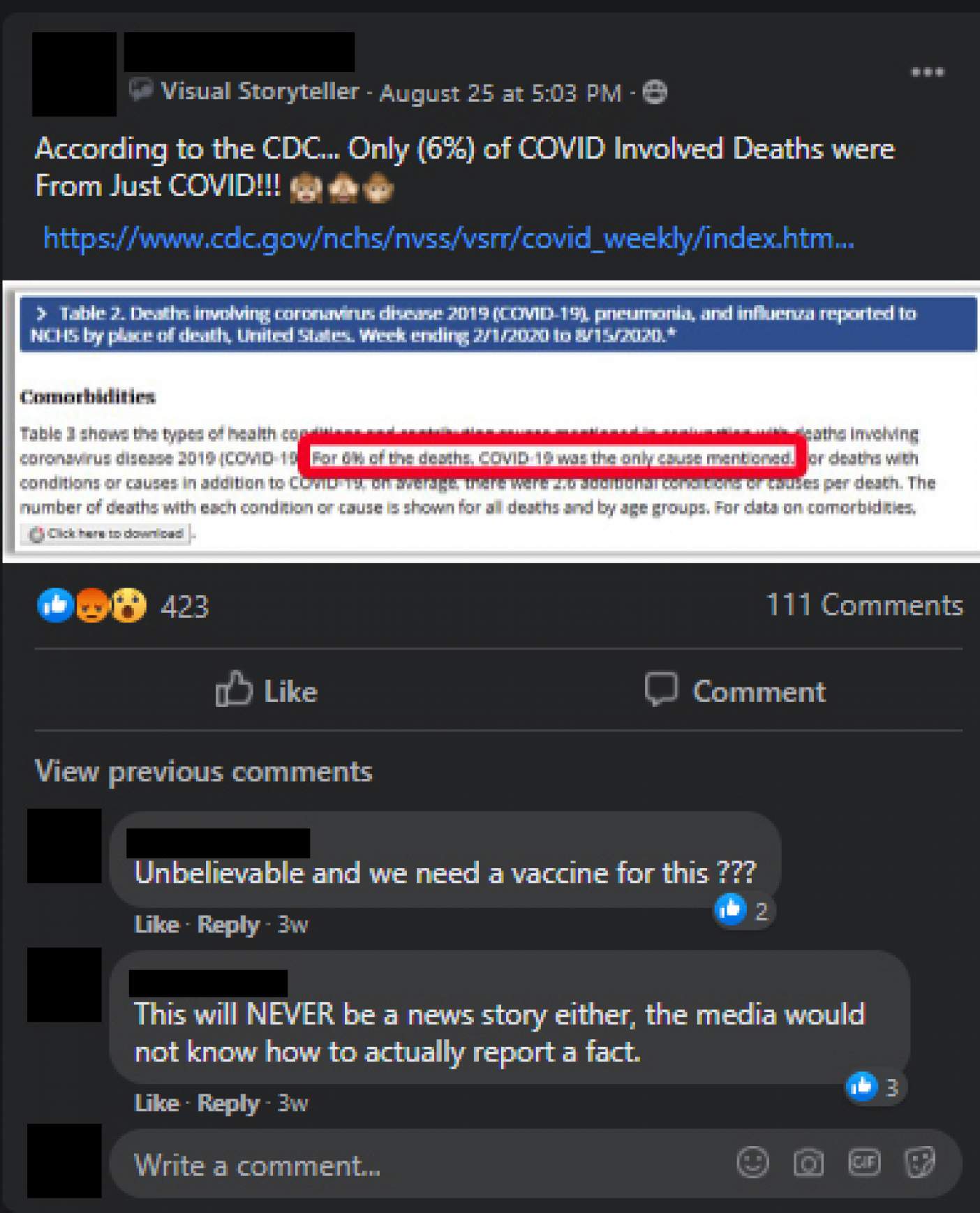

A CDC report sparks a conspiracy

In an August 2020 report about COVID-19 deaths in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed a now commonly understood fact: People who already face serious health challenges face a heightened risk of dying from the respiratory disease.

“For 6% of [COVID-19] deaths, COVID-19 was the only cause mentioned,” the CDC noted in an analysis of more than 150,000 death certificates that attributed COVID-19 as playing a role in the fatality. The report continued: “For deaths with conditions or causes in addition to COVID-19, on average, there were 2.6 additional conditions or causes per death.”

This dry assessment of COVID-19’s terrible toll on Americans with pre-existing health conditions would initiate a frenzy of conspiratorial indignation.

A booster of the QAnon conspiracy theory — a right-wing movement with anti-Semitic roots whose adherents falsely believe a cabal of Satan-worshiping pedophiles runs the world — seized on the CDC report. In a Twitter post, the QAnon acolyte quoted a Facebook post that inaccurately proclaimed the federal agency had “quietly updated the Covid number to admit that only 6% of all the 153,504 deaths recorded actually died from Covid.”

Similar false claims swept major social media platforms. President Donald Trump retweeted the falsehood before Twitter removed it and other tech platforms alerted users to the misinformation.

But nothing could undo the damage. The misinformation had lit up an enclave of the internet steeped in suspicion about public health efforts to curb COVID-19. Doctors like Dr. Chad Tamez faced yet another piece of viral COVID-19 misinformation to battle.

“I can’t tell you how many times I saw that one reposted on Facebook,” he said.

A shifting (mis)information diet

The very nature of the pandemic makes it fertile ground for conspiracy theories, which tend to thrive on anxiety and other negative emotions.

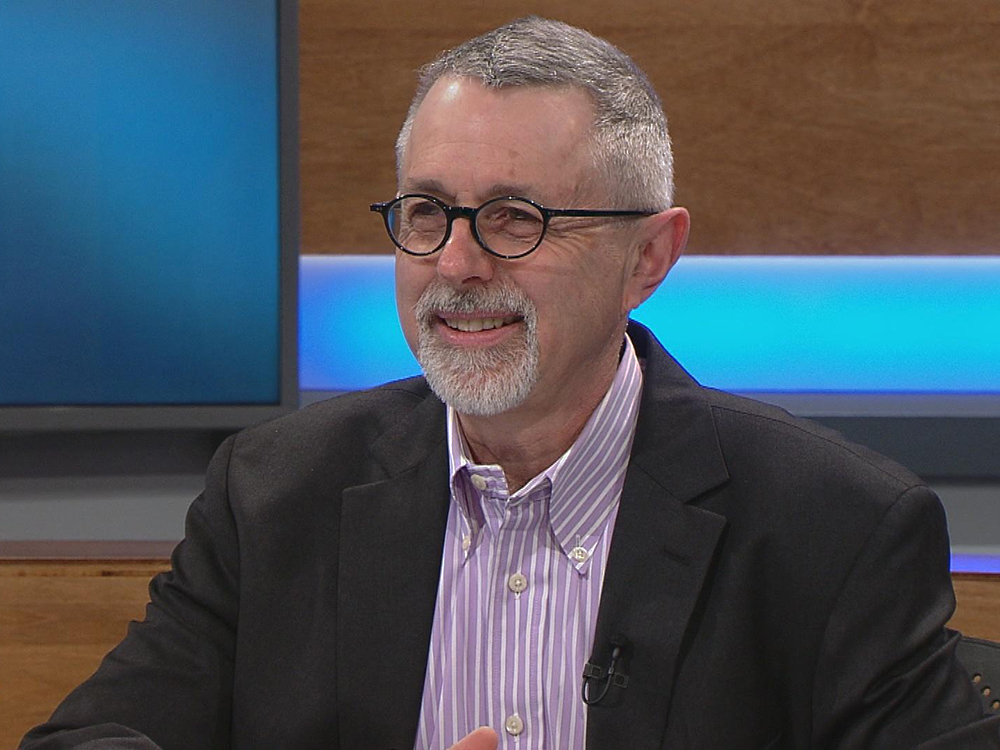

“Misinformation about COVID [is] almost a perfect carrier for the kind of viral fear and anger that then spreads through social media networks,” said Lewis Friedland, a professor of journalism and mass communications at UW-Madison who studies how shifts in the media landscape affect politics and society.

Wisconsin’s news landscape has become more fragmented and less reliable over the last decade as newspapers struggle and people increasingly turn to social media, Friedland said.

The trend comes as the pandemic forces Americans to rely on the internet more than ever before — for work, school, socializing and news. When millions of Americans stayed close to their screens during initial stay-at-home orders in the spring of 2020, nearly half of social-media users who responded to a Gallup survey reported that coronavirus content accounted for “almost all” or “most” of what they saw on their feeds.

The majority of Wisconsinites have favored public health policies implemented by the Gov. Tony Evers administration during the pandemic, according to multiple polls. A Marquette University Law School poll conducted in March showed that 86% of voters viewed the closing of schools and some businesses to slow the spread of the coronavirus as appropriate.

That support slipped to 69% by May after the administration extended the stay-at-home order — a move that brought an angry protest to the Wisconsin State Capitol, with attendees decrying economic harms and infringements on freedom. The aggrieved also congregated online — in newly created Facebook groups with names like “Open Wisconsin Now” and “Wisconsinites Against Excessive Quarantine.”

These Facebook groups and similar online forums have mutated into a kaleidoscope where conservative and libertarian ideologies, distrust of authority and rejection of science create an alternative narrative about the pandemic.

The groups have become a proving ground for misinformation that leverages the copious amounts of confusing and imperfect COVID-19 data public health agencies are pumping out daily.

That includes the false interpretation of the CDC’s analysis of COVID-19 death certificates.

An Aug. 25 post in the private Facebook group “Wisconsinites Against Excessive Quarantine,” which counted more than 120,000 members as of late October, offered a version of the conspiracy theory. The group was created by a family of gun rights activists who manage a broader network of state-based Facebook groups with similar names.

Misinformation spreads quickly when it’s easy to remember and confirms pre-existing biases — especially when it contains a kernel of truth. Presented without proper context, the seemingly straightforward statement “for 6% of the deaths, Covid-19 was the only cause mentioned” is easily digested and regurgitated by those disinclined to believe the virus is deadly.

(By Oct. 22, 1,703 of the 186,100 known COVID-19 cases in Wisconsin had resulted in death. Meanwhile, older people and people of color have accounted for a disproportionate number of COVID-19 deaths in the state.)

The Facebook post struck a chord with group members determined to view it as evidence of a deliberate government ploy to overstate COVID-19’s severity.

Muddying the waters

Opponents of pandemic-related restrictions have also circulated subtle forms of disinformation.

That includes the MacIver Institute, a conservative think tank based in Madison with a history of misrepresenting data and seizing on isolated facts to advance a misleading narrative that the pandemic is less serious than what has unfolded.

MacIver published anonymously authored articles in late September accusing the Wisconsin Department of Health Services of using “bad math” in calculating test-positivity for COVID-19. The articles did not indicate the author had consulted anyone with expertise in epidemiology.

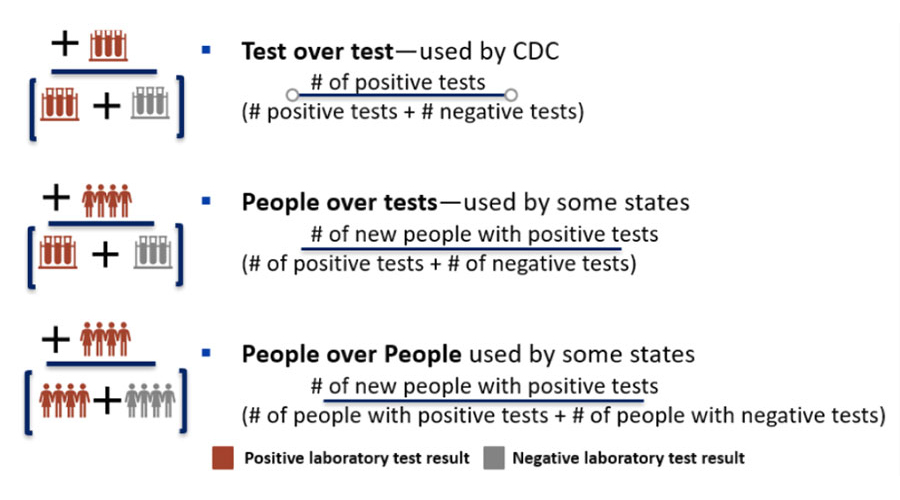

When testing is widely available, the metric, which measures the percent of COVID-19 tests with positive results, can help epidemiologists gauge whether an outbreak is growing. Test-positivity rates can be calculated in different ways, according to the CDC.

Common methods include: dividing all positive tests by total tests, dividing the number of people with positive test results by total tests, or by dividing the number of people with positive results by all people tested. These methods produce different daily results, but if performed consistently, assess trends in the spread of COVID-19.

The CDC uses the first method, citing the limited data it receives from some states.

Wisconsin’s health department has divided people with positive results by people tested from the beginning of the pandemic. In doing so, the agency has included only individuals’ initial negative test results in its calculations. As more repeat testing occurs, an incrementally increasing number of daily negative test results aren’t included in the state’s positivity-by-people calculations.

MacIver described the methodology as a “systematic error” that “wildly distorted” the state’s positivity figures.

However, Ajay Sethi, a public health and infectious disease epidemiology researcher at UW-Madison who has taught a course about public health conspiracy theories, called the accusations “unnecessarily alarmist.”

“Nobody is being a renegade and doing something that’s not CDC protocol,” he said.

Still, Sethi added there is some merit to MacIver’s contention that excluding individuals’ repeated negative results from positivity calculations could eventually affect the trend.

“[B]ut we [are] not at that point,” he said.

Sethi called the state health department’s method for calculating positivity — people over people — “the best way to do it … because the disease affects people.”

This method helps epidemiologists understand how the disease is spreading in a population, Sethi said. Measuring positivity by tests is less helpful for understanding that question, he added, especially when many people are receiving multiple tests.

Sethi underscored that tracking positivity in any of the ways the CDC outlined has merit, so long as the method is consistently applied so trends in positivity can be tracked over time.

At the end of September, MacIver took credit for the state health department’s move to also start tracking COVID-19 positivity by tests. Bill Osmulski, a long-time Wisconsin conservative political writer, told WisContext he authored the MacIver articles and was “very pleased” the state added the metric.

The agency’s secretary-designee, Andrea Palm, said the state did not drop its original metric tracking positivity by people, but noted the additional calculations help contextualize its data.

“We’ll continue to make those kinds of additions moving forward,” Palm said in an Oct. 1 press briefing.

Sethi reiterated that test-positivity, no matter how it’s calculated, cannot solely signal the severity of the pandemic.

Consequences of misinformation

Public health officials in Wisconsin are finding it increasingly difficult to do their jobs against the whirlwind of coronavirus misinformation and animosity.

Jeanette Kowalik, who resigned as health commissioner for the city of Milwaukee in September, said misinformation combined with racism and sexism she faced prompted her to leave for another job. But Kowalik said she doesn’t blame anyone for reacting to confusing and sometimes changing official statistics with skepticism.

But Kowalik did blame social media for spreading much of the misinformation her department combated in the early days of the pandemic. She said much of it centered on false claims about the susceptibility of Black people to the coronavirus or blaming people of East Asian descent for its spread.

Kowalik lamented a continuing onslaught of misinformation related to COVID-19, which have ranged from the CDC deaths analysis conspiracy theory to lurid fantasies characterizing face masks as satanic.

Misperceptions about the disease’s severity could provide a false sense of security, particularly for people with health challenges that could put them at higher risk of serious disease or death, Kowalik added.

“I’m one of those people — I’m high risk,” she said. “I have multiple autoimmune conditions. Does that mean it’s OK if I die prematurely?”

Kowalik is not the only public health officer in Wisconsin to quit under the mounting pressure of misinformation and pandemic politics.

The health officer for Sauk County, Tim Lawther, announced his resignation in early October, citing political pressure from county leaders to ignore scientific evidence about the pandemic.

In Sheboygan County, officials shelved a proposal to use local COVID-19 data to inform new county health orders. It also would have boosted the local health officer’s enforcement power. However, Facebook groups trafficking in misinformation fomented a backlash that led the county board to pull the proposal.

The brouhaha was set off by “a local radio station [which] incorrectly reported that the county was seeking to force people to be vaccinated, close businesses, put people in jail, and that the county board was going to vote on the proposed ordinance the next day,” wrote Sheboygan County Administrator Adam Payne in an article for the Wisconsin Counties Association.

“Facebook went wild and the damage was done,” Payne added.

A pandemic election

The pandemic’s outsized role in the rancorous presidential election only magnifies the misinformation problem.

As he seeks reelection, President Trump, who is well-versed in the art of distortion, has been the nation’s most prominent purveyor of inaccurate information about the disease. He has habitually offered a rosier outlook of the pandemic than his administration’s health officials, and has advocated treatments that range from unproven to dangerous. Even after an October 2020 outbreak at the White House infected Trump along with a number of high-level officials, he resisted new infection-control precautions upon returning from the hospital.

Trump’s political appointees have followed his lead, undercutting scientists’ recommendations and downplaying the disease’s severity.

In Wisconsin, multiple Republican officeholders appear to have taken their cues from the president.

U.S. Rep. Tom Tiffany has declined to adhere to public health recommendations about physical distancing and the use of face masks at campaign events. He was one of 17 Republicans who on Oct. 2 voted against a bipartisan U.S. House resolution condemning QAnon, and has boosted the MacIver Institute’s misleading claims about state data.

U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson attended a party fundraiser while awaiting COVID-19 test results, another violation of public health guidance. He later tested positive.

Even after his diagnosis, Johnson decried what he termed “unjustifiable hysteria” over the disease that has killed more than 223,000 Americans in about nine months. Even after contracting COVID-19, Johnson said he remained opposed to mask mandates, agreeing with Republicans seeking to overturn a mandate ordered by the Democratic Gov. Tony Evers.

Meanwhile, 72% of Wisconsinites surveyed for a Marquette University Law School poll published Oct. 7 said they supported requiring masks in public, with self-identified Republican respondents roughly split on the issue.

Globalized misinformation

False claims about COVID-19 are circulating on social media far beyond the U.S.

In China, conspiracies about the origins of the virus have surged on social media around moments of conflict between Chinese and U.S. government officials. That’s according to research conducted by Kaiping Chen, a UW-Madison professor who studies how people make sense of complex scientific topics online.

Chen pointed to two episodes when conspiratorial posts on the Twitter-like Chinese platform Weibo spiked: one in March around the time President Trump first referred to the coronavirus as the “Chinese Virus,” and another in April when he announced a ban on applications for employment-based green cards. Both episodes heightened tensions between the U.S. and China, but Chen said she did not have enough evidence to prove they caused the spikes in online conspiracies.

But Chen also surveyed about 1,000 people from diverse backgrounds in China about their views and knowledge on a variety of scientific topics, including COVID-19. It probed respondents’ nationalistic propensities by asking about their feelings on their own country, as well as their feelings about foreigners and people from different backgrounds — what Chen calls “outgroups.”

“When one downgrades outgroups — like ‘I am better than you in every aspect’ — this is when people have more misperceptions of every science topic I looked at,” Chen said.

While direct comparisons across cultures are speculative, Chen said a similar dynamic may apply to Americans who have nationalist mindsets. She pointed to a rise in white nationalism among far-right extremists in the U.S.

“Hatred of other race groups or other people from another country is not a phenomenon related to a specific country,” Chen said, highlighting racist misinformation at the pandemic’s outset that associated COVID-19 with people of East Asian descent.

Confronting the infodemic

Public health officials are considering how to combat the maelstrom of misinformation swirling around COVID-19.

“That is a key component of our pandemic response,” said Amanda Simanek, a professor of epidemiology at UW-Milwaukee.

“It’s not just treating patients,” said Simanek. “It’s not just testing. It’s not just contact tracing. Parallel to that, we have to help translate the science … in a way that manages misinformation.”

Simanek is part of a group of women epidemiologists, public health demographers and other researchers who have harnessed social media to explain COVID-19 and combat misinformation.

The group, called Dear Pandemic, has published dozens of reports targeting COVID-19 misinformation. (Malia Jones, a UW-Madison social epidemiologist and WisContext contributor, serves as editor-in-chief.) But combating misinformation without inadvertently spreading it further is a tricky task.

“We don’t love to necessarily focus on amplifying a toxic message,” said Lindsey Leininger, a Dear Pandemic member and professor at Dartmouth College. “Instead, we flip the narrative, and we talk about the durable lesson that comes from each piece of toxic misinformation.”

Leininger called this work “information hygiene,” but remains all too familiar with the challenges these efforts pose.

“This cacophony of different measures is helpful for targeting specific needs to specific places, but it is really confusing to those of us in the public trying to make sense and make comparisons across places and times,” Leininger said. “So it breeds confusion. It breeds uncertainty. And confusion and uncertainty are a crucible for misinformation.”

Dr. Chad Tamez said he’s focused on having respectful one-on-one conversations with his patients in West Bend who remain suspicious about COVID-19. At the same time, he understands where they’re coming from.

“I think people are tired, and they just want some good news,” said Tamez. “And so any bit of good news, even if it’s misinformation, seems to spread like wildfire.”

Tamez is steering interested patients toward sources like the CDC and Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

COVID-19 cases steadily climbed in Washington County, home to West Bend, in September and October. By late October, dozens of new cases were being reported almost every day, as opposed to a handful of new daily cases reported in the spring.

Tamez, whose daughter tested positive for COVID-19 in mid-October likely after being exposed at school, said the reality of the pandemic was bearing down on his community, whether people wanted to face it or not.

“I guarantee you, three months ago people were looking at each other going, ‘I don’t even know anyone who has this, do you? This seems fake,’” he said. “And now, I can almost guarantee you every person in the county knows someone personally who has it.”

Howard Hardee, a fellow at Wisconsin Watch and First Draft, an organization that trains journalists to detect and report on disinformation, contributed to this report. Wisconsin Watch collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.