When COVID-19 took root across the United States in early 2020 the illness quickly overshadowed other public health priorities. The effects of this novel coronavirus were identified as grave and far-reaching, and the disease eclipsed a much more familiar threat to human health.

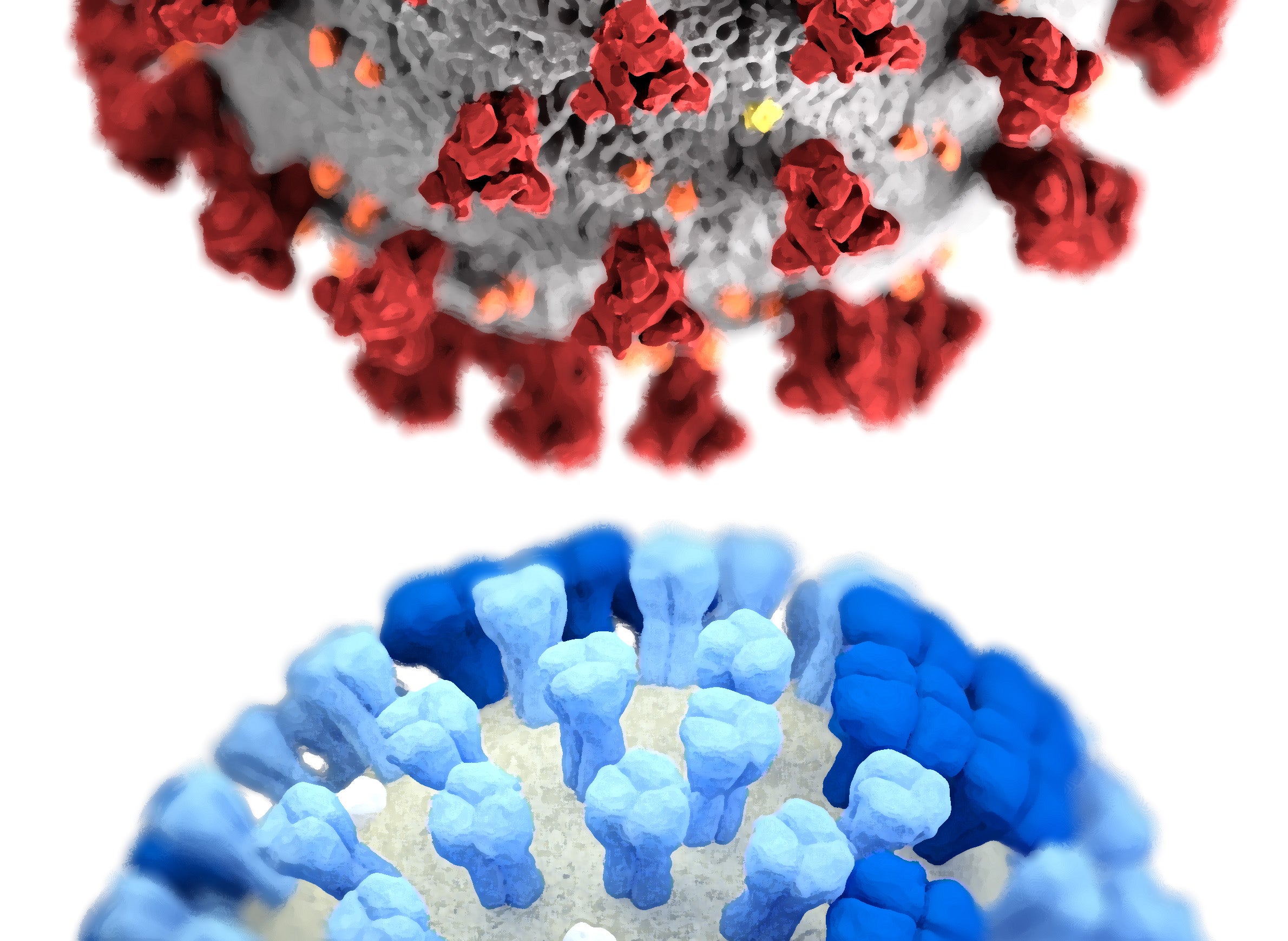

The widespread and ongoing outbreak caused by SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, is defined as a pandemic, accurately characterizing its worldwide span. However, this term has long been commonly associated with another global blight: influenza.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The flu virus has an unfortunate capacity to infect and spread, using humanity’s travel and commerce networks to wreak pestilence the world over. Flu pandemics have been relatively common over the past century, from the infamous 1918-19 contagion to other smaller yet still deadly outbreaks since.

A ‘bizarre’ flu season

Although its final months were overshadowed by COVID-19, the 2019-20 influenza season was serious across the United States and within Wisconsin.

Thomas Haupt, influenza surveillance coordinator at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, said the season was among the worst since the agency began keeping records, and came with some unexpected twists.

“It was a bizarre season,” Haupt said. “It started off with the influenza B virus being the predominant virus until the first part of the year. Historically, when you have influenza B viruses, they usually come after influenza A.”

There were around 4,400 hospitalizations for influenza across Wisconsin between Oct. 2019 and April 2020, with the most acute numbers reported after influenza B strains began to circulate in mid-December, and worsening as infections of H1N1 and other influenza A subtypes started to increase in early January. Two of the four different types of influenza viruses cause significant illness in humans — type B is generally responsible for seasonal influenza, while type A is often associated with more virulent and pandemic-level outbreaks.

The seasonal flu remained a serious cause for concern in early 2020, even as an outbreak of a different respiratory virus prompted lockdowns in Wuhan and other parts of China, and public health authorities started warning about its potential global reach.

In a Feb. 7 interview on PBS Wisconsin’s Here & Now, state epidemiologist Ryan Westergaard discussed the first case of COVID-19 identified in Wisconsin at the time and detailed the preparations being made by the state health department for the disease, which was threatening to become a pandemic. Even with concern growing about the novel coronavirus, state health officials still cautioned Wisconsinites to take precautions to prevent influenza.

February 2020 was an outlier in terms of diagnosed influenza cases in Wisconsin over the past decade. Around 3,000 Wisconsinites tested positive for influenza in its first week., when the U.S. had just 12 confirmed cases of COVID-19, and there were around 31,000 cases worldwide.

Altogether, around 36,000 people tested positive for influenza in Wisconsin during the 2019-20 season. (Testing for influenza is typically conducted in cases where patients are experiencing or at risk of more severe outcomes, and the actual number of infections over the season is higher.) There were 4,442 hospitalizations related to the flu over the season, with 624 patients admitted into intensive care and 176 requiring mechanical ventilation. In total, 167 people died of influenza in Wisconsin over the course of the season.

“Our rates of intensive care admissions and ventilation were very close to being at the highest that we’ve ever had,” Haupt said. “With the exception of the 2017-2018 season, and that was the season that the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] is calling one of the worst and most severe we’ve had in the last 40 years.”

Hospitalizations for influenza topped 7,500 in Wisconsin during the 2017-18 season. While the flu landed fewer people in the hospital in 2019-20, there was a significant uptick in hospitalizations for ages 18-50, and Haupt said pregnant and post-partum women were hospitalized at the highest rate since the state began monitoring that statistic.

(In comparison, in roughly the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Wisconsin Departmentof Health Services reported over 6,000 hospitalizations related to the virus, and over 1,000 deaths.)

In an August 2020 interview with WisContext, Westergaard said influenza had remained the greater threat to public health through February and early March compared to COVID-19. Meanwhile, as the coronavirus pandemic took off in April, flu activity began to subside.

“As happens every year in the spring, the seasonal influenza epidemic wanes and resolves and goes away,” said Westergaard.

Efforts to track rates of influenza infection in Wisconsin became more complicated toward the end of the 2019-20 season, as cases of COVID-19 proliferated. The illnesses share some key symptoms, including fever, muscle aches and respiratory problems. For a period in May, cases of influenza-like illnesses reported through the CDC FluView system seemed to flare in Wisconsin, even as the number of influenza infections fell nationwide. This disparity was due to a health system miscoding COVID-19 cases, Haupt said.

Influenza-like illnesses are defined by the CDC as a fever accompanied by a cough or sore throat. These symptoms complicated the process of diagnosing early cases of COVID-19, particularly when tests were in short supply. Despite the similarities, and not insignificant risk posed by the flu – on average, one out of every thousand cases of influenza will result in death – COVID-19 has proved to be much more deadly. More than six months into the pandemic, COVID-19 has a case fatality rate of around 3 deaths per hundred confirmed cases in the U.S. and 1-2 deaths per hundred confirmed cases in Wisconsin. However, an unknown number of undiagnosed infections and related excess deaths adds uncertainty to this figure

“It became clear that [COVID-19] was the most significant public health threat,” Westergaard said. “It’s become the most significant public health threat of our lifetimes as the epidemic has continued to spread throughout the world.”

Averting a ‘two-headed epidemic’

As public health officials gained a better understanding of the gravity of the threat posed by COVID-19, attention to influenza diminished. However, as the rates of novel coronavirus infections remain high in the U.S., the pandemic is coinciding with another flu season.

The precautions encouraged in response to COVID-19 may have helped to slow the spread of influenza in the spring. Since both viruses are airborne and spread in similar ways, actions like physical distancing, use of masks, increased handwashing and other efforts encouraged in response to the coronavirus are also effective at preventing transmission of influenza.

The weather also likely had a hand in the outcomes of the 2019-20 influenza season. Kathryn Schmit, an infectious disease physician in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, explained influenza thrives in colder, less humid environments, leading to a season that typically peaks between January and March in the Northern Hemisphere.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the annual influenza season typically gets rolling in May and June, when winter is starting. This timing offers some insight on how the ensuing season might unfold in the Northern Hemisphere. Public health organizations that track influenza commonly monitor the strains and severity seen in Australia and other places south of the equator, Westergaard explained. This information also helps the World Health Organization and collaborating organizations determine which strains should be included in vaccines on a rotating basis for both hemispheres.

The COVID-19 pandemic could introduce complications to this annual process.

The 2020 flu season in the Southern Hemisphere has been comparatively mild so far, with relatively few cases compared to a typical year, and the response to COVID-19 is thought to have played a role. Australia, New Zealand and other nations in the Southern Hemisphere enacted stringent policies to tackle the pandemic, which have also been effective in inhibiting influenza.

In a Sept. 3 interview on Wisconsin Public Radio’s Central Time, state influenza surveillance coordinator Thomas Haupt expressed hope that a similar pattern would unfold in the Northern Hemisphere’s flu season.

“People in the Southern Hemisphere are having an extremely low incidence of influenza this year, less than they have ever seen before, probably in the last 20 years.” Haupt said “We’d love to have that come and be the same thing in the Northern Hemisphere, but we also have to be concerned that the influenza season will take off. We don’t want people to become complacent.”

The outlook for the 2020-21 flu season in the U.S. remains unclear, though, given the nation’s far different response to COVID-19 and the ongoing high high rate of new cases roughly half a year into the pandemic. Scientists have been trying to assess what COVID-19 means for influenza infections, but as is the case with myriad aspects of the pandemic, the situation is new and therefore forecasting is difficult.

A new school year complicates matters even more, starting not too long before when the influenza season normally gets rolling in October.

As students attend schools on a patchwork basis, Schmit said it remains unclear how children’s ability to spread COVID-19 compares to what is known about adult transmission. About 7-9% of confirmed cases in the U.S. are among those younger than 18, and children have lower rates of hospitalization than adults. In Wisconsin, people under 19 account for 14% percent of cases.

At the same time, the rate of childhood cases of COVID-19 increased over the summer, and Schmit noted familial cluster and observational studies have shown children are able to spread the virus to family and other close contacts.

“School-aged children have the highest incidence during an outbreak [of influenza] in a community. These children can then cause secondary spread to adults and other children,” Schmit said.

As state and local governments adjust coronavirus-related public health restrictions such as mask requirements, and as employers and other organizations implement their own precautionary measures, influenza may have a harder time spreading. However, if efforts to contain COVID-19 fall short, a concurrent outbreak of influenza could produce additional stress on the healthcare system.

“The biggest concern is that we’re going to have a two-headed epidemic of respiratory viruses in the fall,” said state epidemiologist Ryan Westergaard.

Health care providers are advised to test for other respiratory viruses as well, Haupt told Central Time. He said many will utilize a battery that tests for up to 19 different viruses that may be circulating in the community during colder months.

Westergaard, Schmit and Haupt each offered the same guidance: Get a flu shot.

While the influenza vaccine can vary in effectiveness from year to year, those who get it are about half as likely to become sick from that virus, Schmit said. Even when the vaccine doesn’t fully prevent infection, it encourages the generation of antibodies that can reduce the severity of the flu and reduce the time needed to recover.

Haupt emphasized the CDC encourages people to get their influenza vaccine as soon as it’s available, and no later than the end of October.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.