Editor’s note: This article was originally published on March 6 and has since been updated, with the most recent changes made on July 28.

For people in Wisconsin who are interested in better understanding the COVID-19 pandemic and the ways they can protect themselves, their families and their communities, here are explanations for common questions and additional resources.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

1. What is COVID-19, what causes it and how does it spread?

COVID-19 is a serious illness that emerged in central China in late 2019 and subsequently spread around the world. The disease was first identified in the U.S. on Jan. 25, 2020, with the first infection in Wisconsin announced on Feb. 5. Cases across the U.S. rapidly increased over subsequent months, with the total confirmed count reaching about 3.5 million by the middle of July. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is tracking cases and deaths from the disease in the U.S.

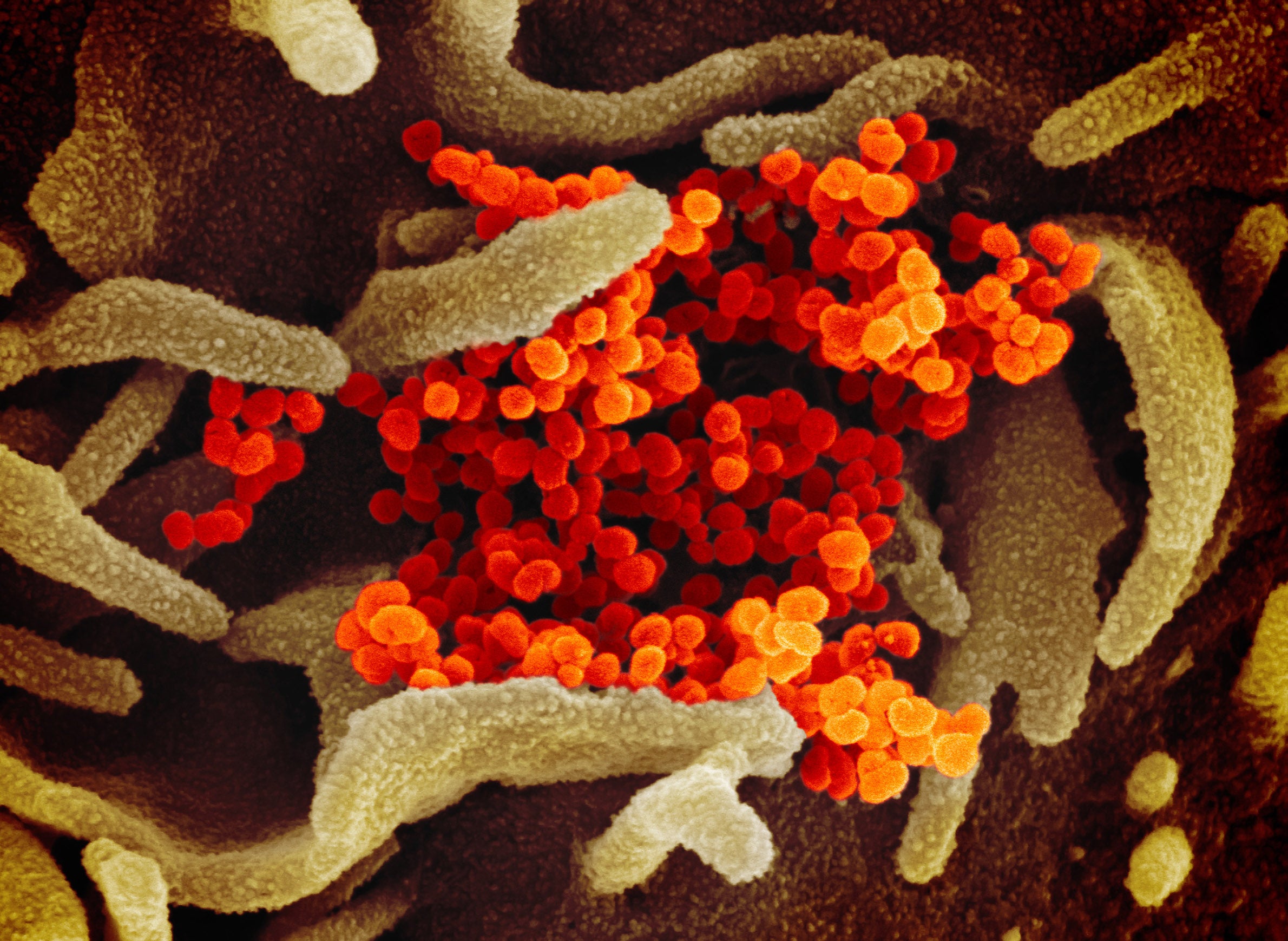

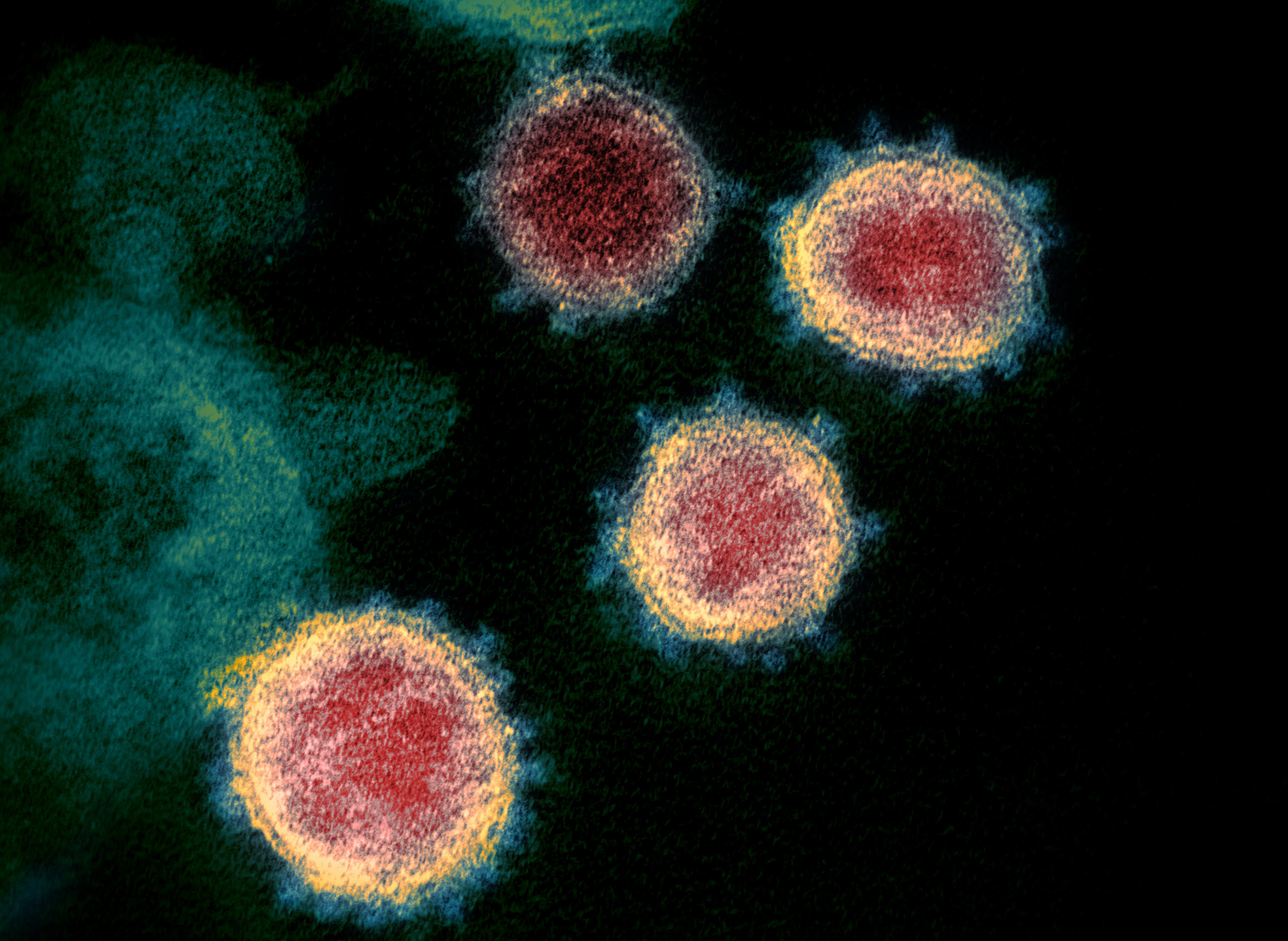

The disease is caused by a coronavirus. These types of viruses can cause several types of illnesses, including dangerous diseases like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), as well as the common cold. COVID-19 infection can have relatively mild effects, but it causes more severe illness among some patients who contract it, and the disease can be fatal. The World Health Organization officially designated the name of the new virus as SARS-CoV-2, and on March 11 declared the widening public health crisis to be a pandemic.

The virus is understood to primarily spread through close contact between people via respiratory droplets. Some people who are infected but do not appear to be ill are able to spread the virus, but it is thought that the sicker an individual is, the more contagious they are. People may also become infected after touching a surface that has the virus on it and then touching their face.

2. What are the symptoms of COVID-19?

The symptoms of COVID-19 include fever or chills, cough, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, fatigue, muscle or body aches, headache, new loss of taste or smell, sore throat, congestion or runny nose, nausea or vomiting and diarrhea. These symptoms can begin two days to two weeks after initial exposure to the virus.

A majority of people diagnosed with COVID-19 have mild or moderate symptoms. The risk of serious cases increases with age and for people with underlying medical conditions or who are immunocompromised.

3. Who is at risk of catching COVID-19?

Anybody who is exposed to SARS-CoV-2 may be at risk of contracting COVID-19, which is spreading in communities around the U.S. People at high risk of exposure include healthcare workers and those with close contact with someone diagnosed with COVID-19. Additionally, many infected individuals may not show symptoms but nonetheless could spread the virus through respiratory droplets.

4. What is the status of COVID-19 in Wisconsin and around the world?

Numerous cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed in Wisconsin and the disease is spreading in communities. State, federal and international public health agencies are working to provide up-to-date online information about the status of COVID-19:

- The Wisconsin Department of Health Services maintains a COVID-19 informational page with guidance for the general public and healthcare workers. The agency also maintains an can follow the status of testing, cases, hospitalizations, recoveries and deaths in the state.

- The Wisconsin Hospital Association is tracking data related to COVID-19 hospitalizations and availability of beds, personal protective equipment, ventilators and more around the state.

- The CDC maintains state-level data about COVID-19 cases and deaths.

- The WHO issues regular situation reports about the number and locations of COVID-19 cases and deaths, and information about public health protocols and research being conducted around the world.

The number of cases in Wisconsin started growing rapidly during the second week of March.

Public health researchers around the world are also tracking the pandemic, with Johns Hopkins University maintaining an interactive global map of COVID-19 cases, fatalities and recoveries.

5. What can people do in response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

The CDC recommends people emphasize basic hygiene practices like proper handwashing to reduce their risk of infection. Other prevention practices include avoiding touching the eyes, nose and mouth, staying home as much as possible, maintaining 6 feet of physical distance from others in public and wearing a tight-fitting cloth face covering in public, avoiding contact with those who are sick, practicing appropriate sneezing and coughing etiquette, and frequently disinfecting objects and surfaces that are regularly touched.

The CDC maintains that physical distancing remains the best way to slow the virus’s spread.

In early April, the CDC began recommending that healthy people wear tight-fitting cloth face coverings while in public settings where physical distancing recommendations are difficult to adhere to, such as at grocery stores and pharmacies. The mask guidance urged medical-grade masks and respirators be preserved for use in healthcare settings.

Some local health departments in Wisconsin have issued mandates requiring the use of face masks in specific spaces.

Medical face masks have been in short supply in 2020 as global demand has skyrocketed. The CDC is providing guidance to healthcare workers who face shortages on strategies for conserving masks.

Other ways to respond to a local outbreak are centered on being ready when daily life is disrupted. These preparations include being ready for self-quarantine or shelter-in-place orders, having a ready supply of prescription medications, and having a couple weeks of shelf-stable food items on hand.

6. What is the state’s public health response to COVID-19?

Public health officials in Wisconsin began mobilizing for a possible local outbreak of COVID-19 in January when the epidemic remained mostly confined to China. As the disease spread, Wisconsin officials prepared for potential surges in demand for medical care, as well as for the need to isolate patients and quarantine individuals to slow the spread of COVID-19.

On March 12, Gov. Tony Evers declared a public health emergency in Wisconsin, which would run 60 days through May 11. That declaration authorized the state Department of Health Services to remove regulatory and logistical barriers to the procurement and distribution of vital medical supplies, including personal protective equipment and ventilators.

Due to a growing number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, the Evers administration issued a stay-at-home order on March 24, which was originally set to run through April 24. On April 16, the state extended the order through May 26.

The order barred public and private gatherings of any size outside of individual households. It also required businesses deemed non-essential to healthcare, childcare, food provision, transportation, finance and a select few other services to close or require employees to work from home. The order maintained prior restrictions requiring salons, barbers, day spas and similar businesses to close and restaurants and bars in the state to shutter dining rooms (with takeout and delivery still allowed). The move came after some municipalities had already ordered the closure of most public accommodations.

On April 20, the Evers administration unveiled a plan for easing movement restrictions and reopening more workplaces in Wisconsin. Dubbed the “Badger Bounce Back,” the plan called for easing restrictions gradually and set benchmarks for doing so. These benchmarks included a sustained downward trajectory in new illnesses, expanded COVID-19 testing and beefed up contact tracing, among other criteria. The plan followed the administration’s extension of the stay-at-home order and efforts by Republican leadership in the state Legislature to challenge the action before the state Supreme Court.

On May 13, justices ruled 4-3 in favor of the challenge and struck down the stay-at-home order extension. The decision, which took immediate effect, invalidated the order and made it unenforceable. Instead, the ruling stated the Evers administration would need to work with the state Legislature’s rulemaking committee when crafting future orders.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court’s decision came less than 48 hours after Evers’ original public health emergency order expired, leaving no statewide orders in effect in response to COVID-19. Instead, county and municipal health departments were left to set local guidance. Multiple local public health departments have issued local orders that set varying rules for the capacity and operation of restaurants, taverns and other businesses, the size of public gatherings, the use of face coverings and other actions intended to slow the spread of the virus.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court’s decision came less than 48 hours after Evers’ original public health emergency order expired, leaving no statewide orders in effect in response to COVID-19. Instead, county and municipal health departments were left to set local guidance. Several of the state’s most populous regions issued local orders that largely reflected the invalidated statewide order, which have been subsequently rescinded, expired or loosened.

The state’s public health emergency order also activated the Wisconsin National Guard. Members transported dozens of Wisconsin residents home from California after being stranded on an infected cruise ship, and subsequently mobilized to provide assistance to the state or local jurisdictions. National Guard members have acted as poll workers assisted with the pandemic response, including at testing centers, treatment sites and medical supply warehouses.

At the federal level, President Donald Trump declared a national emergency on March 13. That declaration allowed the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to waive or modify some federal healthcare regulations to aid a speedier response. On April 4, the Federal Emergency Management Agency announced aid would be available to Wisconsin after granting the state’s request to declare COVID-19 a major disaster.

In the absence of statewide public health restrictions, the state health department’s strategy to manage the ongoing pandemic is centered on contact tracing with local health departments taking the lead. The state is providing tracing assistance to local communities, particularly those facing a surge in cases.

7. How does COVID-19 testing work in Wisconsin and who can get tested?

Tests for COVID-19 are available at numerous locations across Wisconsin, including hospitals, healthcare clinics and temporary testing locations.

Demand for testing outstripped the capacity of labs in Wisconsin during the outbreak’s early weeks. The limited availability of testing through Wisconsin’s public health system spurred many private health providers to develop or purchase their own COVID-19 tests. These actions significantly expanded the number of tests being conducted in the state, though shortages of supplies remained an issue.

On March 30, Gov. Tony Evers announced a partnership with Wisconsin-based technology and healthcare companies aimed at strengthening testing supply chains and quickly doubling the number of COVID-19 tests performed each day. As a result of expanded testing capacity, state health officials announced April 10 they were relaxing previous guidelines that called for restricting COVID-19 tests to hospitalized patients, healthcare workers, residents and workers at long-term care facilities and high-risk individuals.

Beginning in early May, local public health officials worked with the state and National Guard to set up temporary community testing sites where anyone with symptoms of COVID-19 could be tested, with some sites drawing large numbers of residents.

Wisconsin enacted a COVID-19 response package on April 15, which requires health insurers to cover COVID-19 testing and bars insurers from discriminating against people with the disease or who have recovered from it. It also ensures Wisconsin qualifies for newly available federal Medicaid funding. The federal government also enacted a COVID-19 response package that included a provision for free COVID-19 testing nationwide.

8. How are hospitals, health clinics, emergency responders and other healthcare facilities like nursing homes responding to COVID-19?

Hospitals and other healthcare facilities in Wisconsin are treating patients who have contracted COVID-19. These efforts include seeking to stock enough N95 respirators, gowns, gloves, eyewear and other necessary medical equipment to provide adequate care. Hospitals across the state reported shortages of medical face masks and other necessities as the outbreak began, and have implemented protocols to conserve their supplies and share resources with other facilities.

Hospitals have restricted visitation of patients. In order to prepare for a surge in cases, hospitals also initially canceled elective procedures, though by late April a number of health systems in the state were restarting or planning for this type of treatment once again. Following the lifting of the state’s stay-at-home order in May, hospitals across the state grappled with how to restart suspended services and reorient care while facing major financial strain and surges of disease.

Officials fear a steep rise in cases could swamp hospitals. Healthcare professionals are asking residents to continue to heed public health guidance and remain at home as much as possible in an effort to slow the disease’s spread.

Medical offices in the state have screened patients before their visits and are asking them to reschedule appointments if they show any respiratory symptoms. Dental offices temporarily closed, but many resumed operations by late May with additional precautions in place.

Nursing homes and other long-term care facilities have restricted visitors since the outbreak started spreading in the state.

Emergency responders across the state have prepared for possible calls for mutual aid, while those in rural areas have changed how they operate.

9. How are schools responding to COVID-19?

Gov. Tony Evers issued an order mandating the closure of all public and private K-12 schools in the state beginning March 18. In its extension of the stay-at-home order on April 16, the state announced schools would remain closed for the remainder of the academic year, and some school districts moved forward with pass-fail grading scales for students given challenges posed by virtual learning. The state Supreme Court’s May 13 ruling invalidating the state’s stay-at-home order did not affect school closures, which the majority said could remain in effect without a clear legal explanation.

At the pandemic’s outset, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction provided pandemic information to districts, including guidance related to closures and for how to talk with children about the risks of COVID-19. The uncertainties and disruptions surrounding COVID-19 may be particularly alarming for children, and parents are recommended to share information and answer questions.

In late June, the agency released guidelines for how local school districts operate in the fall. The recommendations outlined a variety of possible schedules that would mix in-person and virtual instruction. Each of Wisconsin’s 421 school districts would retain the ability to set its own schedules and protocols.

The CDC has provided guidance for elementary and high schools and for colleges and universities to address the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March, UW System campuses and private universities halted classroom instruction, encouraged students to move from dormitories, canceled university-sponsored travel, and canceled spring commencement ceremony plans. Summer courses have also gone online, though UW campuses announced plans to restart in-person instruction in the fall, which may include testing all students, faculty and staff for COVID-19.

Some Wisconsin colleges moved toward pass/fail grading for the spring 2020 semester, and a number of public and private universities in the state planned to refund students tens of millions of dollars associated with room and board and campus fees.

The resulting financial strain prompted the UW System Administration and UW campuses to require employees to take unpaid time off. The UW System additionally announced layoffs affecting dozens of employees at the end of May. UW System President Ray Cross also outlined a restructuring proposal that would eliminate some degree programs and affiliated faculty and staff on many campuses.

10. What recommendations do public health officials have for closing and reopening workplaces and public gatherings, and for the status of travel?

Officials from the state Department of Health Services are recommending that people work from home if possible unless they are employed in an essential sector. On March 24, the agency intensified an existing ban on public gatherings, prohibiting all public and private gatherings of any size outside of individual households, with the exception of some facilities considered critical infrastructure. The ban had a major impact on business in the state and jobless claims skyrocketed, straining the state’s unemployment system and exposing underlying problems.

The CDC offers recommendations for how workplaces, first responders, healthcare facilities and organizers of mass gatherings address the COVID-19 pandemic.

The WHO developed a set of conditions it recommends should be met before officials begin relaxing restrictions on gatherings and public movement as the pandemic progresses and local outbreaks begin to subside.

Local governments across Wisconsin have explored ways to boost sectors of the economy heavily impacted by movement and business restrictions while adhering to ongoing public health guidelines. One effort explores expansion of outdoor seating at restaurants.

Large public gatherings in the state, including summertime concerts and festivals, continue to be canceled, postponed or radically downsized due to the pandemic, including Summerfest, the Wisconsin State Fair and the Democratic National Convention slated for Milwaukee.

The pandemic is also affecting both domestic and international air travel. Many nations have closed their borders, and the land borders between the U.S. and Canada and Mexico have been ordered to close to most traffic. On March 19, the U.S. State Department warned Americans against all international travel. By mid-summer, U.S. residents were banned from entry to most nations.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a rapidly changing public health situation, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing updated information and guidance as each becomes available. WisContext, PBS Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Radio are continuing to report on COVID-19 and its status in Wisconsin. Ongoing coverage is available here.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.