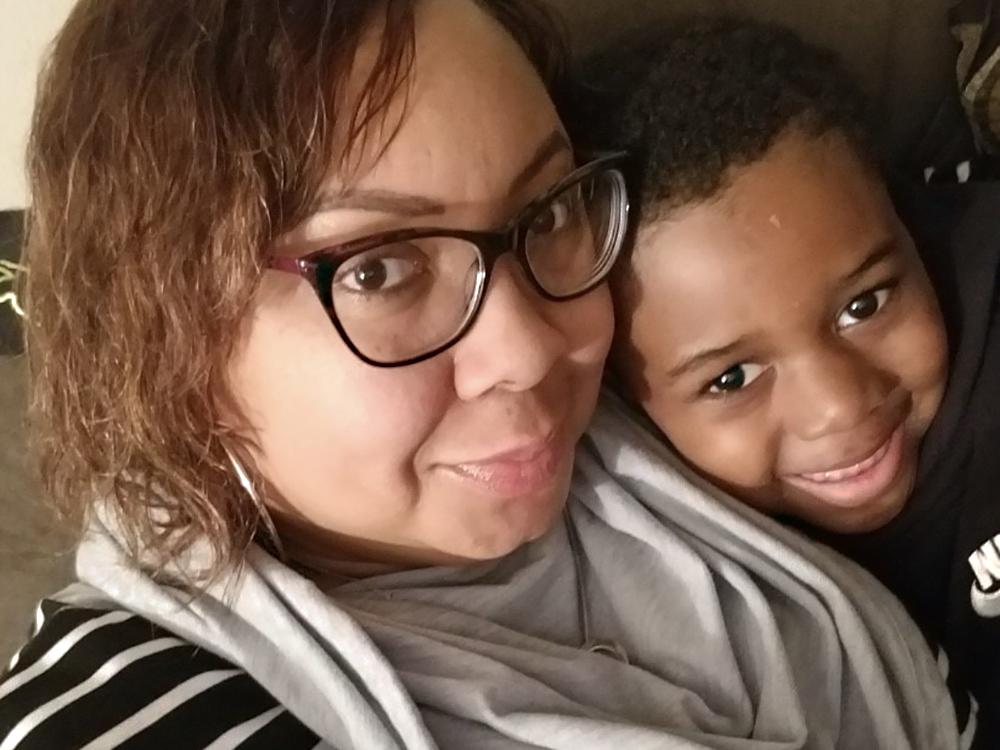

After seven days of enduring a series of miserable symptoms — shortness of breath, numbness in her hands and feet, headaches and extreme, aching pain — Adrienne Lathan’s doctor told her it was time to take a coronavirus test. Confirmed positive and suffering from acute pneumonia, Lathan spent six days fighting COVID-19 at a Milwaukee hospital at the end of March. She nearly died.

“I just remember going to the bathroom,” says Lathan. She awoke in her bed, surrounded by hospital staff. “The nurse said they thought they lost me.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Being told she was well enough to finish recovering at home was a relief to Lathan. She felt worlds better, but knew immediately she still had a long way to go before she would feel normal again.

“So the big thing was just the oxygen, because it really couldn’t really leave home,” says Lathan. “They did give me the tanks to take with me — they look kind of like the helium-type thing.”

Lathan was on oxygen for 30 days. For the most part, she was able to self-isolate at home, with plenty of help from friends and family to get groceries and other supplies.

Lathan’s father Jerald Coleman — who had been hospitalized to treat congestive heart failure and gout since February — tested positive for COVID-19 and passed away due to complications from the virus. Her own hospitalization kept her away from her father in his final moments — but being home in recovery meant she could attend his funeral in person.

“The only time I did come out [of isolation] was for my dad,” Lathan said.

A long haul to recovery

It’s been a long year, but 2020 has likely felt even longer for people who have contracted and battled COVID-19.

Jeff Pothof is an emergency room physician and chief quality officer for UW Health. When treating COVID-19 — whether for patients getting initial tests in the ER or returning concerned that their symptoms are getting worse — Pothof says it’s all about triage, determining which patients will most benefit from being hospitalized versus those who seem more likely to get better on their own at home.

Some patients clearly need hospitalization.

“[If] you can’t breathe without me putting you on a ventilator, or you’re not able to breathe without me putting you on supplemental oxygen — at that point the decision is pretty slam dunk,” said Pothof.

But many COVID-19 patients might appear relatively healthy in the ER, only to face an uncertain risk that their illness could take a turn for the worse. That’s when more subjective factors have to be considered.

“So do I feel like this person is going to be able to get back to the emergency department if they get worse? Do they have support at home?” said Pothof. “Those aren’t purely objective medical criteria. But from the patient’s perspective, they’re just as real and just as important as a lab result or an oxygenation reading.”

Adrienne Lathan is still recovering. She only felt back to half strength by the start of June, two months after she was discharged from the hospital. By July, she was feeling physically stronger, but more deeply felt the mental toll of her illness.

“I don’t think people realize that it does affect you emotionally and mentally,” says Lathan. “In my case, I’m dealing with survivor’s guilt because not only did I have to deal with losing my dad, I lost other family members and friends.”

Lathan’s experience demonstrates how long and complicated recovery from COVID-19 can be — with these bouts discussed in Facebook groups like Survivor Corps and Long Covid Support Group and via #LongCOVID on Twitter — and is increasingly a focus of scientific research into the virus.

Early in the pandemic, the World Health Organization published a situation report that noted 80% of COVID-19 are “mild or asymptomatic.” At the end of July, though, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a survey study in which researchers found 1 in 5 COVID-19 patients still felt far from “normal health” two to three weeks after testing positive.

But what about one month? Or three months?

There are many COVID-19 patients who suffer from symptoms of the virus for three months or longer. Known as “long haulers” or “long-termers,” they experience respiratory symptoms, “brain fog,” fatigue and other ailments long after their initial acute illness, new symptoms that are only now being understood. There’s still a lot to learn about the long-term effects of the disease.

Medical professionals and patients agree that it’s an oversimplification to define any specific number of people as having “recovered” from COVID-19. Some feel better after a week. Others spend several months going in and out of emergency rooms.

Several long-term patients told the Appleton Post-Crescent that they experienced months of chronic fatigue, persistent coughing, shortness of breath, and even damaged vocal cords from extended time on ventilators. Some with these chronic symptoms believe they may never fully recover.

How does the public health system track that breadth of experience?

Defining recovery and its difficulties

When it comes to assessing COVID-19 risks at the population level, how and when people are deemed to be recovered becomes a more complicated question.

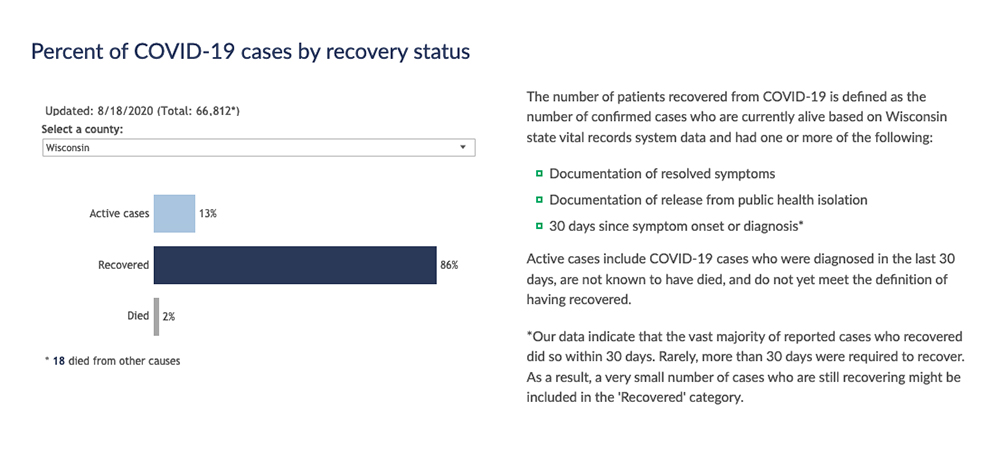

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services tracks a broad swath of metrics related to COVID-19 in the state on a daily basis, including the number of tests, new cases, deaths, hospitalizations and more, breaking them down by county and certain demographics. The numbers related to COVID-19 cases in Wisconsin and each of its 72 counties include a tally of those considered to be recovered, those considered to be active, and those that ended in deaths.

Every day, the state updates a set of charts that highlight the number of active cases, recovered cases and deaths on county and statewide levels, using data sourced from the Wisconsin Electronic Disease Surveillance System. At the same time, many local health departments likewise maintain online counts of cases by status within their jurisdictions. However, the state does not provide daily data over time for the numbers of cases it labels “active” and “recovered,” and therefore does not provide a picture of how these numbers fluctuate over time.

The issue is the term “recovered” and its use as public health shorthand in a way that does not have the same meaning as getting better, or even feeling better.

“For now, we use the term ‘recovered’ because it is a commonly used measure in other states and locations,” said a state health department spokesperson, who noted the term’s limitations and explained the state does not conduct follow-up inquiries about cases over a long period of time.

Early in the pandemic, labeling cases as “recovered” when they were considered to no longer be infectious was how the agency sought to define a metric to help better assess risk, said agency Secretary-designee Andrea Palm. However, due to the increasing evidence that infection can result in a widely differing array of outcomes — anywhere from an asymptomatic positive test result to a months-long bout — it became clear that this term is imprecise.

“We’re still learning about this disease, about symptoms, about the long tail that it has to some people as it relates to it lingering — the fact that sometimes you can recover from symptoms and then they will flare back up again. So we’re still learning a lot about what it means to be a positive case of COVID-19,” said Palm in an Aug. 12 press briefing. “‘Recovered’ was certainly the right word at the time. I think our knowledge and understanding of the disease has evolved and will continue to evolve.”

Nevertheless, the state employs a specific approach for determining if COVID-19 patients are considered “recovered” in public health terms, and applies that definition to the case numbers it updates daily.

A COVID-19 case is deemed recovered if a state health department official can confirm one of the three criteria: one, a patient is no longer experiencing fever, cough and other signs of respiratory infection; two, local health department staff have confirmed this patient has isolated from others for 10 days since the onset of symptoms; or three, 30 days have passed since a patient tested positive for COVID-19.

The individual experience of each COVID-19 patient is documented through their medical records, and eventually through follow-up care from their regular primary care provider, if they have one. That means patients without health insurance typically receive less follow-up to document their long-term symptoms. However, public health staff contact all confirmed cases for follow-up, regardless of insurance status, according to the agency.

Follow-up contacts — made by a combination of local county health department staff, public health nurses, health educators and staff from the state’s contact tracing team — ask patients who tested positive for COVID-19 about any current symptoms, the date these issues started and how they’ve changed. These patients also get asked about other people they’ve encountered and places they’ve been, aiding contact tracing efforts.

Every positive case gets an initial call to determine if a patient meets the criteria for “recovered.” If the patient still has fever, cough or respiratory symptoms, they continue as an “active” case in the state’s tracking, and are told to isolate from others. Cases can also be updated by patients themselves via a self-reporting form that they can use to track their symptom progress.

The vast majority of COVID-19 cases are classified as recovered when health officials contact a patient and confirm either a resolution of their symptoms, or that they’ve quarantined for 10 days, ruling out their potential for infecting others, according to CDC guidelines.

After the initial contact, local health departments continue to monitor and check in with active cases depending on their capacity and number of cases in their jurisdictions.

In lieu of further follow-ups and self-reporting, though, health officials often have to make assumptions and rely on benchmarks that assess risk.

What’s the importance of 30 days?

While healthcare providers are tracking patients who experience problems related to COVID-19 for months on end, there isn’t enough comprehensive data on its long-term effects to inform epidemiological models used by policymakers. To solve that data gap, the state health department assumes — based on current data — that the majority of people with COVID-19 will no longer be at risk for infecting others 30 days after their case is reported.

After those 30 days, and if a patient hasn’t died, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services assumes a case to be “recovered” for tracking purposes. However, there are exceptions —if a death is confirmed to be related to COVID-19, even if reported outside of that 30-day window — the agency revises its numbers to include that instance.

ER doctor Jeff Pothof said this 30-day benchmark makes sense based on the patients he’s seeing.

“When you’re trying to look at these large populations, you have to pick some metric — 30 days generally fits well enough,” he said.

While this time frame might not capture how long it takes for patients to truly feel back to normal, public health officials consider it a reasonable estimate of how long it might take to assume that a patient is at minimal risk of infecting others.

The other reason for the 30-day benchmark is that there is simply not enough data to generalize how different people experience recovering from COVID-19.

“There are some secondary conditions that occur [after 30 days] that may lead to death, but that we are not following right now,” said state health department deputy chief epidemiologist Ousmane Diallo in an interview.

Diallo explained the agency doesn’t have access to that level of detail for patient data, though he said that such information will be valuable to track how COVID-19 progresses over longer and longer timescales.

Recovered versus recovering

The concept of “recovery” must be considered differently in medical and public health terms, said ER doc Jeff Pothof. In public health, recovery means a patient can no longer infect others. For healthcare providers, recovery is about getting a patient back to feeling how they did before contracting the virus.

“Say you’re young and healthy, you’ve got no risk factors and you get sick. Seven to 10 days later you feel just like you did before you got sick,” said Pothof. “[Compare that to] someone else who’s elderly, who has underlying lung disease, gets admitted for COVID, gets discharged home or maybe more likely gets discharged to a rehab facility, to a nursing home. That person, it may take them two months to get back to the point where they feel like they’re kind of at their pre-COVID baseline.”

When it comes to gauging numbers of recovered COVID-19 cases, Pothof emphasized this difference is important to bear in mind.

“Recovery is just probably not as specific as a word that we want,” said Pothof.

Instead, a “recovered” case is shorthand for someone who is no longer infectious. When it comes to actually feeling better, a more fitting term would be “recovering.”

“It’s not that you are completely better. It’s that you’re better enough where we think you can complete this process at home,” said Pothof. “There’s a whole array of people in that recovered group, some doing better than others. But it gets tricky. I understand why people want to have that recovered number, but it’s a continuum, not a black and white thing.”

Adrienne Lathan is feeling better, but says the experience taught her the stakes are high with COVID-19, and while policy can be adjusted based on changing data, it’s important to remain vigilant.

“Some people don’t take it seriously until it hits close to them,” said Lathan. “I think more people who survived it or who lost family members or friends need to speak out so that people are taking it seriously.”

Editor’s note: WisContext associate editor Will Cushman contributed to the reporting for this article.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.