Listen to an accompanying Wisconsin Public Radio broadcast story about police unions and law enforcement oversight policies in the state.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Police unions and the labor contracts they negotiate with local governments are seeing renewed scrutiny in communities across the United States. This attention follows a slew of high-profile cases of law enforcement officers resorting to lethal violence under questionable circumstances — incidents that are driving calls for a reassessment of how the public can hold police accountable.

Wages, benefits, working conditions, residency status and disciplinary procedures have been among the issues that police unions negotiate with municipalities. The resulting contracts are typically in effect for a few years until the union and municipality negotiate an update.

However, critics assert that police union contracts can unduly shield officers from serious consequences when they stand accused of misconduct, or may even help fired officers who were found to have engaged in misconduct get their jobs back.

In Wisconsin — the mid-20th century birthplace of public employee unions and an epicenter of union-busting policies in the early 21st century — state law limits the power of police unions to shape officer discipline through contract language more than in other parts of the nation.

A Wisconsin Public Media review of police contracts in eight mid-size and large Wisconsin cities found most language is largely in line with standard public worker union agreements, but there are some differences in negotiated protections for officers.

A fresh spotlight on union power

Public outrage over the killing of George Floyd, a Black resident of Minneapolis, swelled following revelations that the police officer who kneeled on his neck for about nine minutes and subsequently was charged with homicide had been the subject of a long history of complaints but seemingly faced little discipline.

That officer and three others involved in Floyd’s killing were fired less than a day later by the chief of the Minneapolis Police Department, but such swift action is not the norm within American law enforcement. A slower process is more typical, in part because of the considerable leverage unions can have in shaping disciplinary processes and a broad swath of department procedures.

Even with the terminations, a major target of police critics’ ire has been the union that represents the Minneapolis Police Department’s more than 800 officers, and in particular its high-profile and controversial leader, Lt. Bob Kroll.

For years, Kroll has waged a public war against efforts by multiple mayors of Minneapolis to introduce policing reforms, such as one intended to reorient officer training away from combat tactics and toward community-oriented policing. He also quickly came to the defense of the four fired officers and announced a union effort to win them their jobs back.

The Minneapolis police union has long benefited from considerable political influence at local and state levels in Minnesota — wielding power to stymie attempts at reform it sees as a threat to members’ interests, including changes related to disciplinary procedures for officers accused of misconduct.

A central source of this power lies in the labor contract the Minneapolis police union has negotiated with the city, along with a formidable war chest to fund legal battles, according to a former Minneapolis police chief interviewed by the Star Tribune.

A 2018 University of Oxford review of American police abuses linked officer protections commonly incorporated into union contract language with an increase in abuses of power.

But there are limits to how these contracts can protect officers. The same 2018 study cited state labor laws as one check on police unions. In Wisconsin, a specific legal structure defines the police officer disciplinary process.

Police union contracts and discipline

WisContext, PBS Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Radio reviewed the most current police union contracts on file in eight Wisconsin cities: Beloit, Green Bay, Kenosha, Madison, Milwaukee, Racine, Waukesha and Wausau.

These cities are spread across Wisconsin, and home to larger communities of people of color relative to their total populations than the state as a whole.

Police officers in all these cities but three— Green Bay, Kenosha and Milwaukee — are represented by the Wisconsin Professional Police Association, a statewide organization that represents employees of more than 300 local police and sheriff’s departments in the state.

Officers in the Milwaukee Police Department are represented by the Milwaukee Police Association, a local affiliate of the national AFL-CIO.

The local Green Bay Professional Police Association and local Kenosha Professional Police Association represent officers in those cities.

A July 24, 2020 report on PBS Wisconsin’s Here & Now explores how officer discipline rules vary across the state.

Police union contracts usually have terms of two to three years, and negotiations over new contracts are often almost exclusively centered on wages and benefits.

“The parties … they’re mostly concerned with the economic terms and conditions,” said Dale Belman, a professor at the Michigan State University School of Human Resources & Labor Relations. Belman previously taught at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and has worked as an expert witness for various public employee unions, including police unions in Wisconsin.

Contracts also play a role in how officers are disciplined for misconduct.

“Contracts are intimately involved in that process,” said Don Taylor, a professor in the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School for Workers.

Taylor, who has done paid work on behalf of police and other labor unions, argued that police contracts aren’t unique in providing protections for members facing discipline.

“It’s not just police contracts, but all contracts contain some sort of provision that the employer has to follow some type of due process in order to discipline or terminate any employee,” he said.

Aspects of contracts pertaining to officer discipline tend to be renegotiated less frequently and usually only when there is a pressing need to do so, such as the introduction of a new technology that has the potential to significantly impact policing and disciplinary investigations.

“Something like body cameras, for example,” said Robert Bruno, a professor of labor and employment relations at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “What if you ask officers to wear them? It’s really impacting the working conditions.”

It’s in these instances that both the city and police union have a vested interest in coming to a contractual agreement over how to navigate the new working conditions through collective bargaining, Bruno said.

“And typically in any collective bargaining agreement, when you make a substantial change in one section, particularly when you add something new, that has some spillover in other sections,” he said, which can in turn lead to more negotiations.

Discipline and arbitration

An oftentimes tedious negotiating process and the overarching importance of compensation can disincentivize unions and cities from seeking contractual changes that would impact rules and procedures related to discipline.

At the same time, Wisconsin’s Act 10 law, enacted in 2011 to curtail the collective bargaining rights of most public sector employees — with the notable exception of police and firefighters — allows local governments to make unilateral changes to officers’ health insurance benefits.

“They’ve really used that to stem the tide of language changes and language bargaining that you might have seen,” said Jim Palmer, executive director of the Wisconsin Professional Police Association.

These factors perhaps explain why the eight city contracts reviewed by Wisconsin Public Media shared more similarities than differences in spelling out disciplinary procedures.

Most differences centered on details such as those dictating where and when interrogations can occur during internal investigations, or the length of a recruit’s initial probationary period during which they can be fired much more easily than officers with longer service records.

One significant area where the city contracts differed is whether officers are able to appeal their discipline under a grievance procedure and ultimately have a chance of it being overturned by a third-party arbitrator. Several contracts, including those in Green Bay, Kenosha, Madison and Racine, explicitly bar officers from filing grievances in an effort to overturn disciplinary actions.

But the contracts in Beloit, Milwaukee, Waukesha and Wausau do allow officers to file grievances in response to at least some discipline. The contracts’ grievance procedures vary in details but generally call for a stepped approach that escalates toward an arbitration procedure.

The arbitration process often calls for the Wisconsin Employment Relations Commission to supply a specified number of qualified arbitrators to the union and municipality. The two sides can then alternately strike names from this list of arbitrators until only one remains.

The selected arbitrator then hears each side’s arguments and makes a determination that is almost always final.

“There is no question that unions and management keep score on arbitrators,” said Sue Baumann, a former mayor of Madison and current labor arbitrator who has made rulings in Wisconsin and Minnesota on law enforcement discipline disputes. “They know better than arbitrators know how many times an arbitrator has sided or has found for the union or for the employer.”

Arbitrators make their determinations based in part on whether management followed the rules outlined in union contracts and department regulations. Because the language in contracts is often very specific, arbitration decisions can sometimes rest on technicalities, which is one reason critics say discipline shouldn’t be arbitrated.

Arbitrating officer discipline is rare in Wisconsin, Baumann added, thanks to the state’s approach to police department oversight.

“In Wisconsin, police discipline is in the purview of the police and fire commission,” she said.

The role of police and fire commissions

Union contracts are only one element of the legal and regulatory framework that dictates the relationship between police officers and the local governments that employ them.

“Those parameters can be set by the collective bargaining agreement … but there’s almost always also law,” said labor relations professor Robert Bruno.

In Wisconsin, several state laws set parameters for when police officers may face discipline, who is empowered to mete it out and what that process looks like.

Most relevant is a statute dating back to the 1890s that requires municipalities with 4,000 or more residents to maintain a police and fire commission. Commissions are made up of between five and nine residents who are appointed by the mayor. They rule on cases where an officer is accused of misconduct and faces discipline. These cases often originate from within departments, but any “aggrieved person” can file a complaint.

As such, these bodies amount to a type of oversight board that police reform advocates have called for in other places around the nation.

The duties of commissions include hiring and firing police chiefs, administering disciplinary hearings for officers and doling out discipline for serious offenses, including firing. As a result, Wisconsin’s police and fire commissions hold sway over the fate of officers who stand accused of serious misconduct or criminal behavior.

This oversight body is in part intended to limit the potential for cronyism within police departments, though police chiefs remain responsible for conducting investigations of officers accused of wrongdoing, handing down discipline for less serious misconduct, and making recommendations to the commission for more serious disciplinary matters.

The commission structure limits the ability of elected officials, particularly mayors, to respond to community calls for officer discipline. One ongoing example are demands by activists and family members of Tony Robinson, a Black teenager, to fire Matt Kenny, a white Madison police officer who shot and killed the 19-year old during a 2015 incident. The Madison Police Department concluded that Kenny did not violate department rules, and the Dane County District Attorney declined to file criminal charges against the officer.

Police and fire commissions have plenty of critics.

Police reform advocates in Wisconsin say the commissions don’t provide adequate community oversight. They are limited in size, and commissioners typically serve 5-year terms. As mayoral appointees, there is also a potential for partisan influence, though state law bars mayors from appointing members from just one political party.

In Madison, Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway has expressed support for a community push to create a citizen oversight group separate from the police and fire commission, though the legality of such a group has been called into question.

Either way, there is discontent with a commission structure that rarely rules against officers in cases originating from civilian complaints.

The disciplinary process administered through police and fire commissions can be quite slow, and state law allows officers to continue to collect pay while awaiting a decision, even those who are suspended pending a decision in a criminal case where they are a defendant.

Labor arbitrator — and former mayor — Sue Baumann takes issue with Wisconsin’s rigid and often slow-moving disciplinary process for officers.

“The fact that all discipline has to go through the [police and fire commission] and that the police chief can only make a recommendation and the mayor has absolutely no say doesn’t make sense to me,” Baumann said.

“I think we need to be looking at a different model,” she said.

At the same time, the powers that state law afford to police and fire commissions also constrain unions’ ability to shape disciplinary procedures through contract negotiations or to even appeal a commission’s decision.

“[It’s] an extraordinarily high legal standard to overcome,” said Jim Palmer of the Wisconsin Professional Police Union.

Appealing a commission’s disciplinary decision is therefore “very, very rare.” he said. “In the last several years, we haven’t had a single instance of appealing any PFC decision to circuit court.”

More state laws

There are other state statutes that control aspects of the process that governs officer discipline or termination in Wisconsin.

One statute enacted in 2014 requires an outside law enforcement agency to investigate the circumstances surrounding officer-involved shootings. The law was the first of its kind in the U.S., and a handful of states have followed with similar laws.

Labor leader Jim Palmer cited support for that law by the Wisconsin Professional Police Association as an example of how police unions and reform advocates in Wisconsin could come together on an issue that might prove more divisive elsewhere.

“We were a leading advocate for the 2014 law,” Palmer said.

“We’ve long supported measures to increase the accountability and transparency at every stage of that law enforcement employment process — hiring, discipline, terminations,” he said.

More acquiescence from police unions around the nation on issues of accountability may be necessary for them to regain public support and remain in the good graces of larger union organizations, as some local groups have moved to expel police-affiliated chapters.

Meanwhile, a much older Wisconsin statute means that officer discipline in Milwaukee must adhere to a somewhat different process than everywhere else in the state. That’s because Milwaukee is the state’s only “1st class city,” a legal designation for Wisconsin cities meeting specific criteria, including a population threshold.

This 1st-class city status requires a larger review board, in this case the Milwaukee Fire and Police Commission.

Milwaukee’s commission holds greater power than those elsewhere in the state, having the ability to set department policies, as well as ultimate say over the hiring of every officer. Additionally, the commission acts as an appeals court of sorts for most discipline handed down by the police chief.

The Milwaukee commission’s powers also allow it to take over internal investigations into officers accused of crime or misconduct, as it chose to do in a high-profile case involving an off-duty police officer. Michael Mattioli faces a charge of first-degree homicide following an April 2020 party at his home where he is accused of beating Joel Acevedo, who died from his injuries days later.

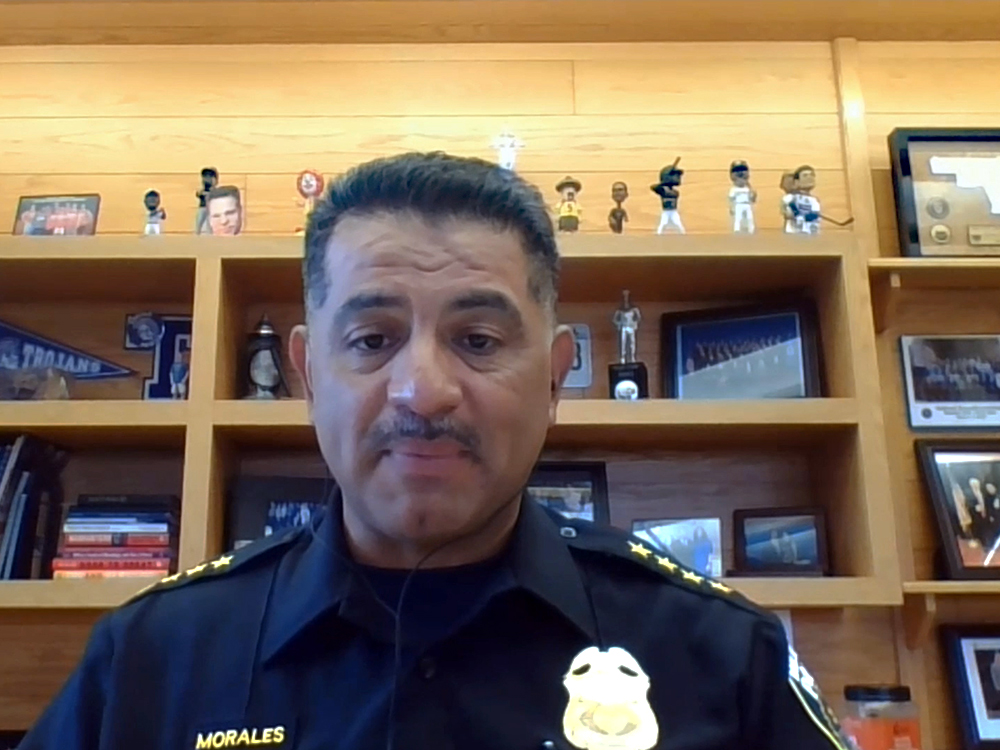

This role means power over Milwaukee Police Department personnel rests with the commission, as was made starkly apparent in July when Chief Alfonso Morales attended a commission meeting not knowing whether it intended to fire him. Members instead voted unanimously to retain Morales as chief while issuing new mandates for officer conduct and tactics.

Other relevant state statutes include Chapter 164, commonly known as the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights. As of 2015, Wisconsin was one of 16 states to have some version of a law enforcement officers’ bill of rights statute on the books, according to The Marshall Project, a digital news organization focused on criminal justice issues.

Such laws generally spell out officers’ privileges when facing internal investigation and interrogations, though how far they extend varies. For instance, Maryland’s law says officers facing possible discipline cannot be forced into supplying a statement to investigators for up to 10 days. The law was cited as one reason why details surrounding the 2015 death of Baltimore resident Freddy Gray in police custody remained obscured from investigators for days.

Wisconsin’s law does not provide as much latitude. First passed in 1979 and amended several times in ensuing decades, the statute outlines due process requirements, including a right to be informed of the nature of the investigation and a right to legal representation during interrogation. It also prohibits local governments from passing ordinances that would bar law enforcement officers from engaging in political activity on their own time or running for office.

There’s also Act 10, signed into law by former Gov. Scott Walker, which left police and firefighter unions largely exempted from the collective bargaining limitations. It has had a relatively minor impact on their contracts.

The political environment related to policing in 2020 has some prominent conservative activists in Wisconsin seeing a potential opportunity to extend Act 10’s collective bargaining restrictions to police officers. Two staffers with the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty penned an op-ed advocating such an action as attention to police unions intensified in the wake of George Floyd’s killing.

That prospect doesn’t sit well with Don Taylor at UW-Madison, or Robert Bruno at the University of Illinois. Both men are defenders of public employee unions, broadly speaking.

“The danger,” said Taylor, “and it’s already manifesting, is that this movement against the rights of police officers and their unions … is going beyond those groups of employees, and it’s going to affect all public sector employment.”

Bruno agreed, adding that he believed police unions would be wise to seek a more conciliatory relationship with local leaders and reform activists moving forward.

A police union “isn’t going to be supported, and isn’t going to be able to sustain itself through a real changing political environment if it isn’t seen as doing two things,” he said. “It’s got to be able to bring democracy into the workplace — police officers need due process, they need rights in the workplace, they need better pay. They need those protections. But they also have got to be seen as bettering society, as working for the people.”

Editor’s note: This reporting is the product of a collaboration between WisContext, PBS Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Radio. PBS Wisconsin’s Zac Schultz and WPR’s Bridgit Bowden contributed reporting to this story.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.