With cases of COVID-19 cropping up in communities around Wisconsin, Gov. Tony Evers declared a public health emergency for the entire state on March 12, 2020. This action adds Wisconsin to a growing number of states and local jurisdictions around the United States that have declared emergencies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the novel coronavirus that has caused it.

The governor’s executive order directs the state Department of Health Services to “take all necessary and appropriate measures to prevent and respond to incidents of COVID-19” in Wisconsin.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

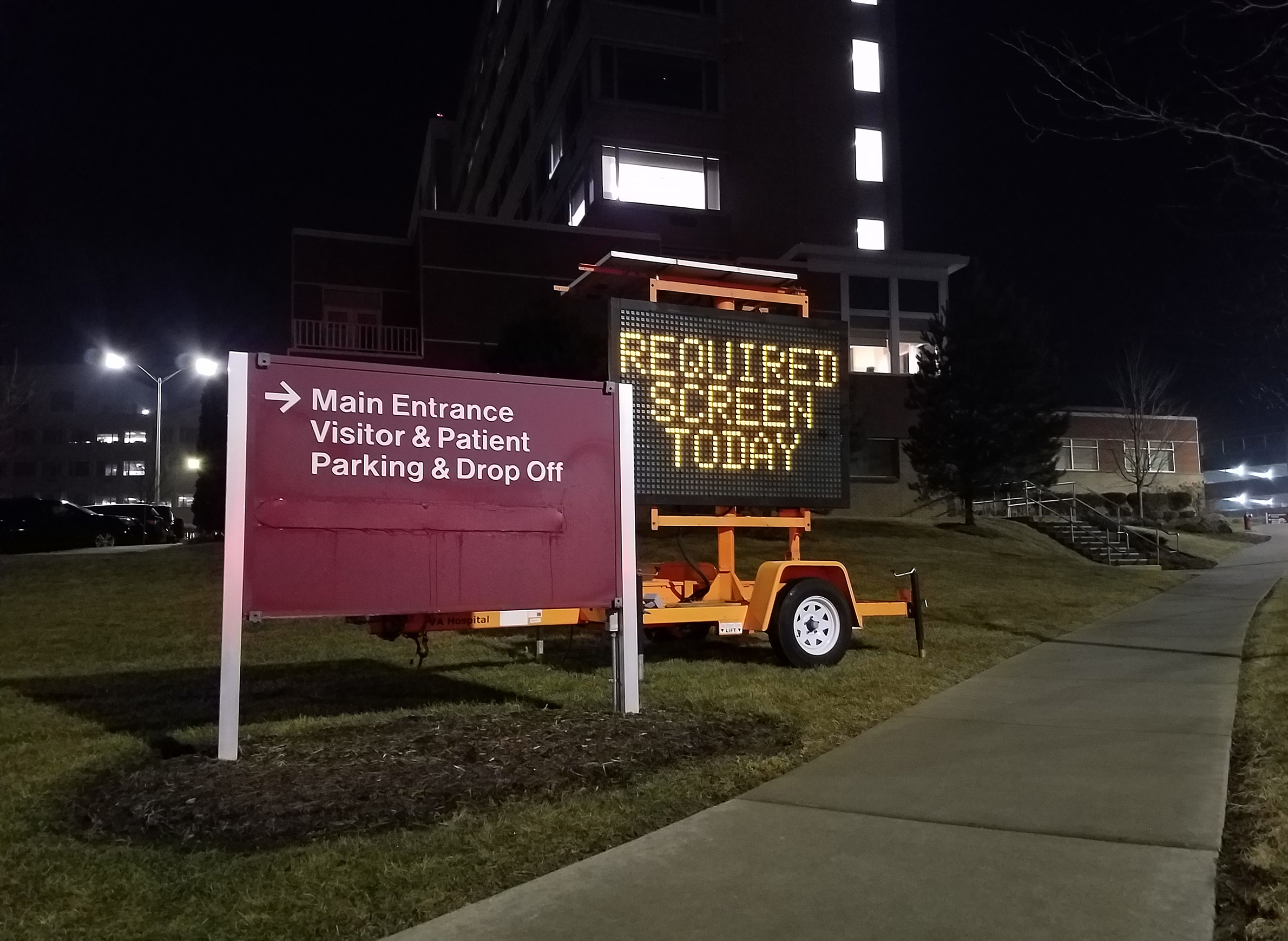

In a press conference alongside the governor, Andrea Palm, the Secretary-designee of the department, said these measures would likely include purchasing vital medical supplies and, in the case of community transmission in the state, canceling or postponing mass gatherings of more than 250 people, restricting visitors to healthcare and nursing facilities, and possibly shuttering schools and daycares.

Besides urging social distancing and directing the state health department to intensify its fight against COVID-19, what does the emergency declaration mean in practice? State law provides some guidance.

Declaring a public health emergency in Wisconsin

Wisconsin law gives the governor powers to declare emergencies in response to natural and human-caused disasters, threats to vital telecommunications systems and threats to public health.

A public health emergency can be declared for all or part of the state. There are no criteria outlined for declaring an emergency or determining its scope. It is left solely at the discretion of the governor.

If the governor declares a public health-related emergency, state statutes say the Department of Health Services “may” be designated the lead agency to respond to the emergency.

Additionally, any emergency declared in the state, whether related to public health or not, “shall not exceed 60 days” unless the Legislature approves an extension by joint resolution. Meanwhile, the power to revoke a state of emergency is reserved to the governor by way of executive order, or to the Legislature through a joint resolution.

Local governments are also empowered to declare a state of emergency within their jurisdictions for various threats that may impair “transportation, food or fuel supplies, medical care, fire, health or police protection or other critical systems of the local unit of government.” State statute also says the length of a local emergency declaration can be as long as “the emergency conditions exist or are likely to exist.”

Emergency powers of the governor and state agencies

An emergency declaration provides significant powers to the governor and state agencies involved in responding to it. These powers are primarily aimed at removing regulatory and logistical barriers to a speedy response.

Under a state of emergency, the governor can prioritize contracts for equipment and services related to the emergency, temporarily suspend any regulations that constrain or delay the state’s response to the emergency, and procure any supplies or facilities the governor deems necessary as part of a response.

In the case of the public health emergency declared in response to COVID-19, the order allows the state Department of Health Services to purchase, stockpile and distribute medications as needed, “regardless of insurance or other health coverage” of the individuals receiving the medication.

Additionally, an emergency declaration often precedes a request for federal assistance.

In the case of the COVID-19 emergency, this could allow Wisconsin gain speedy access to the federal government’s Strategic National Stockpile. The stockpile includes billions of dollars worth of medications and medical equipment, including supplies of ventilators and personal protective equipment like respirators and biohazard suits. The stockpile was created in 1999 primarily to prepare for the possibility of a bioterrorism attack. The 9/11 and anthrax terror attacks of 2001 prompted Congress to allocate additional funding for this resource.

Stockpile warehouses are strategically (and secretly) positioned around the nation to ensure emergency medical supplies can reach any community or state within 12 hours. Pieces of equipment that require power to operate, such as ventilators, are regularly tested to ensure proper functioning. However, some vital supplies in the stockpile, including face masks, may be understocked for the COVID-19 pandemic response.

Military powers

Wisconsin’s emergency declaration laws also empower the governor to authorize the state adjutant general, or chief military officer, to activate the Wisconsin National Guard to assist in the response if necessary.

In the case of COVID-19, the National Guard was immediately activated upon the governor’s executive order to transport dozens of Wisconsin residents from California back to the state, where they would be required to undergo testing for the disease along with a 14-day quarantine. The returning residents had been passengers aboard the Grand Princess cruise ship, which had been stranded off the coast of northern California after nearly two dozen passengers and workers on board tested positive for COVID-19.

Addressing this pandemic

Gov. Evers’ executive order also calls for the state to provide funding to local health departments to help cover costs associated with isolating patients and quarantining people who might be exposed.

“These are potentially disruptive things for people’s lives, and we recognize that,” state Department of Health Services Secretary-designee Andrea Palm said.

In addition, Palm and Evers urged Wisconsin residents to heed public health guidance related to reducing the risk of transmitting the virus, which spreads readily via close personal contact.

The governor acknowledged that forgoing customs and habits such as hugs and handshakes may be a challenge for many but underscored the importance of doing so to protect people most vulnerable to the virus, including the elderly and those with preexisting health conditions.

“‘Wisconsin Nice’ is going to have a different look to it,” he said.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.