When cases of COVID-19 started accelerating around the United States, the University of Wisconsin-Madison was among the first wave of universities to take action. Its administrators suspended in-person classes and directed students and staff to avoid campus in the interest of slowing the contagion’s spread. One century earlier, though, the school faced another pandemic and responded in a very different way.

The end of 1918 is notable as the moment when the First World War came to its conclusion, as well as for the emergence of the H1N1 influenza pandemic that swept around the globe, with their intertwined effects felt by much of humanity. In Wisconsin, the war and pandemic came together in a typical yet tragic way. In a Nov. 7, 2018 presentation at the Wednesday Nite @ the Lab lecture series on the UW-Madison campus, recorded for PBS Wisconsin’s University Place, graduate student Dr. Steven Oreck discussed how the Student Army Training Corps exercised significant influence on the campus response to the flu pandemic.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

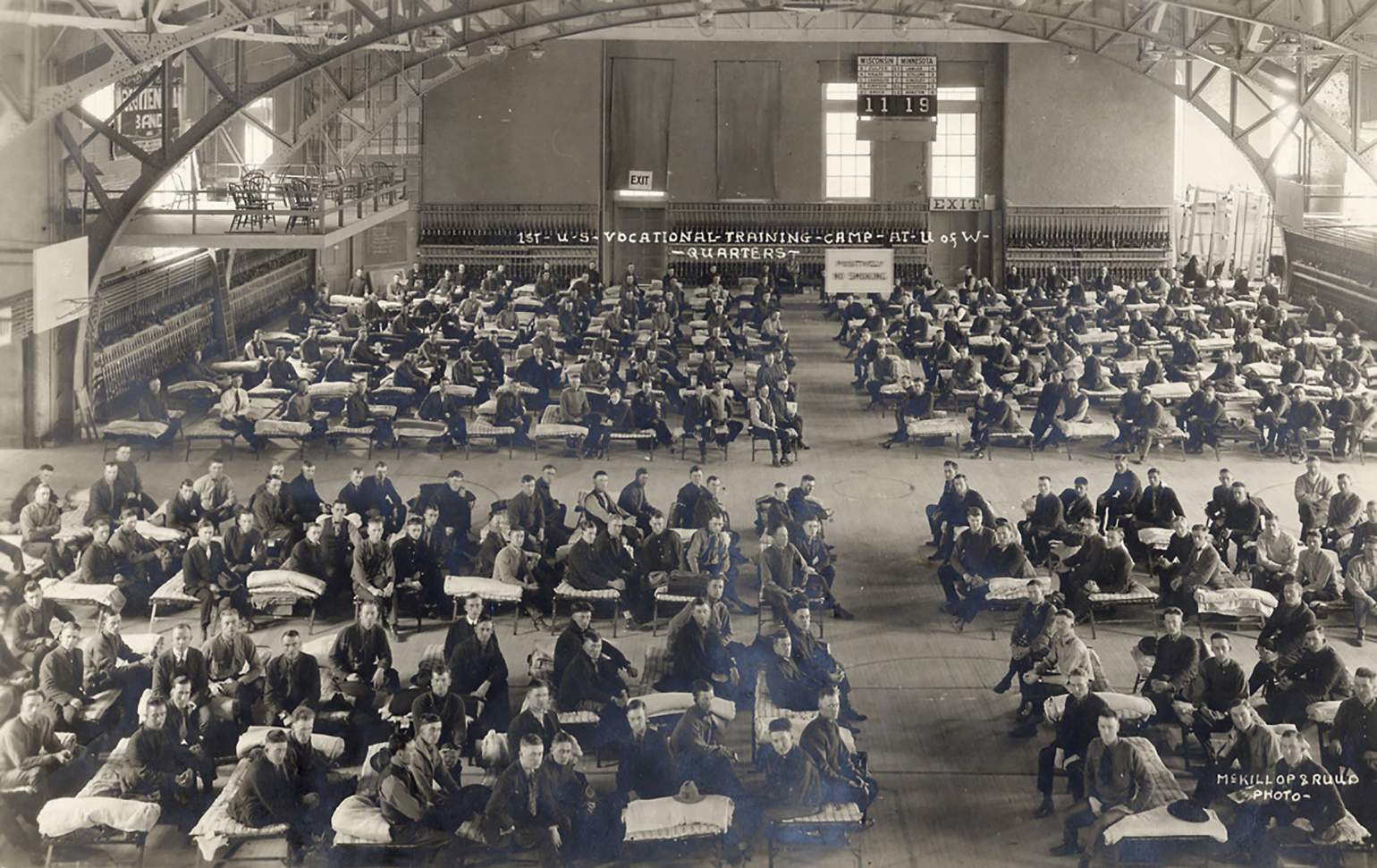

“The relationship between the universities with SATC units and the War Department… was unprecedented,” Oreck said about the World War I-era U.S. military program that was a program operating in parallel with the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. “If the university had an SATC unit, that university was more like a military installation than a normal university.”

The U.S. formally joined the global conflict by declaring war on Germany in April 1917, and over the next year, drew many of the nation’s young men into service. By mid-1918, military training facilities across the country were overwhelmed with the number of recruits, and the SATC was established to provide on-campus military instruction to university students, including at UW-Madison.

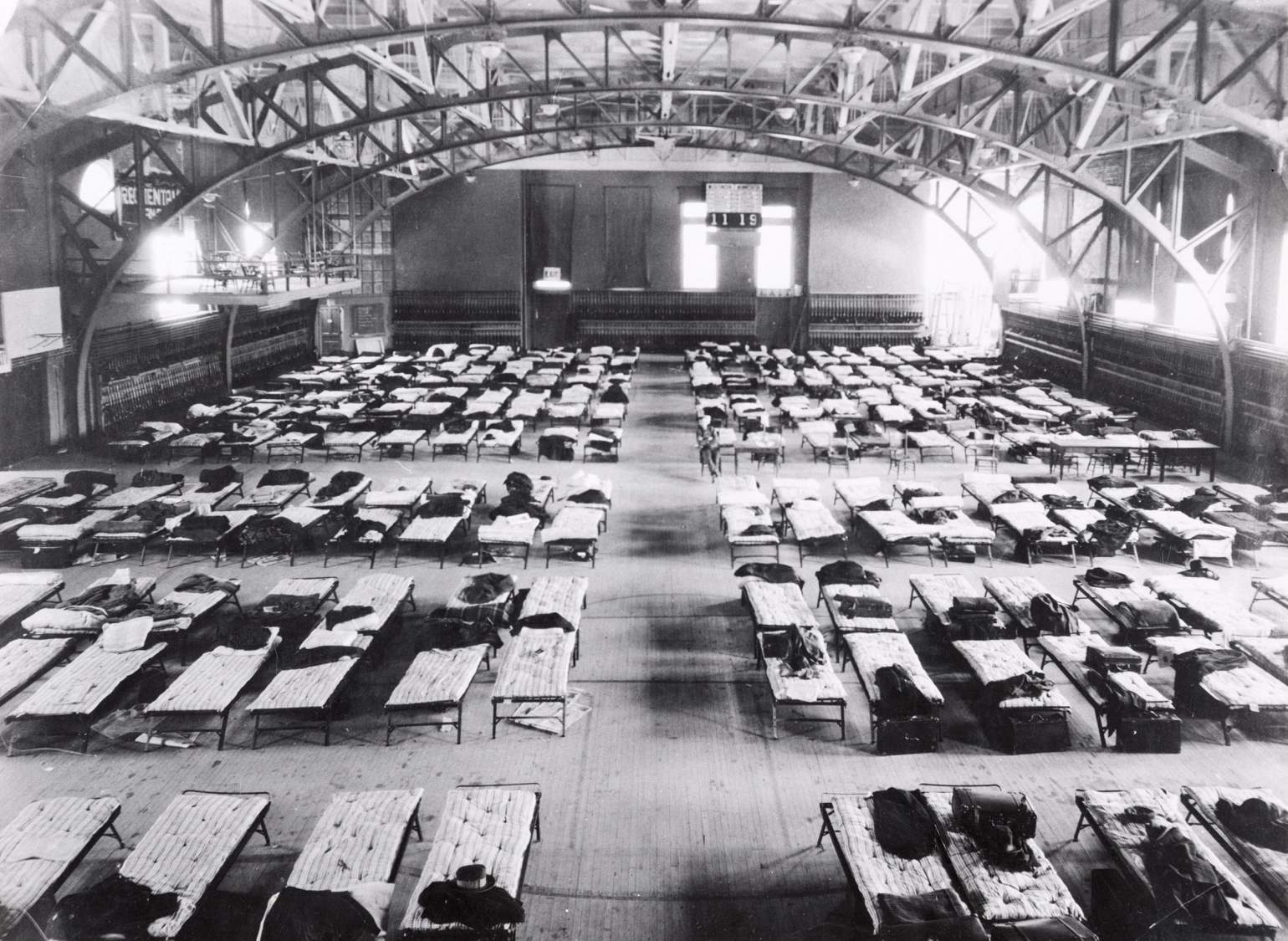

The university had an enrollment of 4,666 when the fall term began on Oct. 1, 1918. This total included 2,577 men in the SATC, who were not permitted to live in private housing or join fraternities. Instead, SATC students lived in makeshift on-campus barracks, including the Armory, now known as the Red Gym. These SATC students slept in beds that were spaced less than two feet apart, Oreck said.

The first signs of illness in those close quarters appeared as soon as the students arrived, but they were dismissed by Dr. Charles Bardeen, then dean of the UW medical school, as a “grippe of colds.” Local newspapers, including The Daily Cardinal, similarly reported that there was no sign of influenza among the students.

“Since morale had become a weapon of war, keeping morale up was simply another battle to be waged and won,” Oreck explained. “Beyond projecting calm to prevent panic, the sunny pronouncements we see in the Madison press during the early period of the epidemic represented an attempt to keep morale up.”

By Oct. 9, the first UW-Madison student had died from influenza — Arthur Ness — and hundreds on campus were ill. On Oct. 10 the Wisconsin State Journal reported that there were 1,000 flu cases in Madison, and the state health officer issued an order closing all public gathering places. While UW-Madison cancelled classes greater than 25 people, the SATC was exempt from state and campus orders, and continued training students with limited modification.

Madison saw the number of influenza cases peak at around 5,000 during the second and third weeks of October, including 943 acknowledged infections among SATC students. Despite the high rate of disease, more than 600 new SATC vocational recruits arrived on campus in mid-October, and 172 of these incoming students had fallen ill by Oct. 22. The University Club, located at the base of Bascom Hill, served as an infirmary.

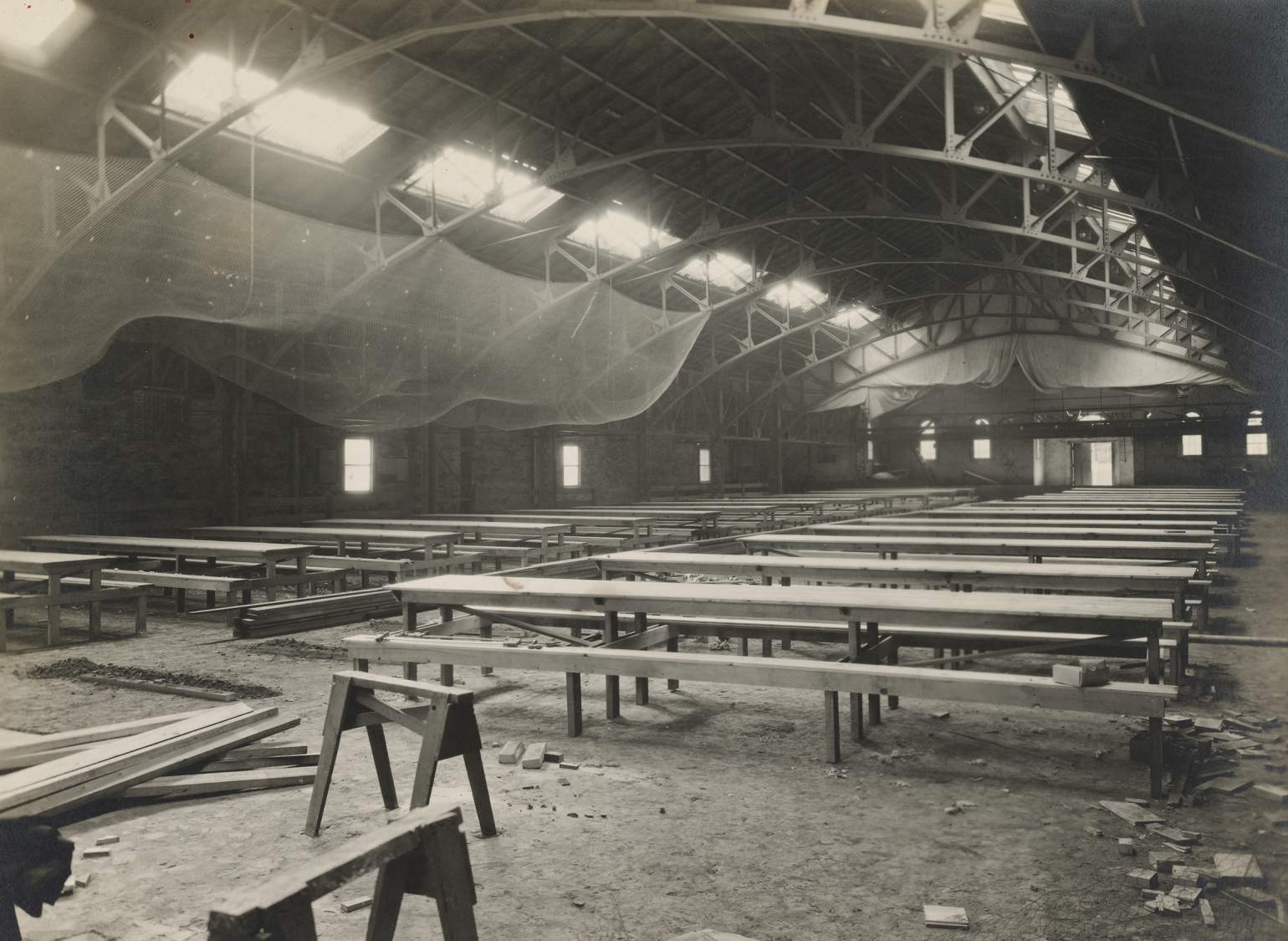

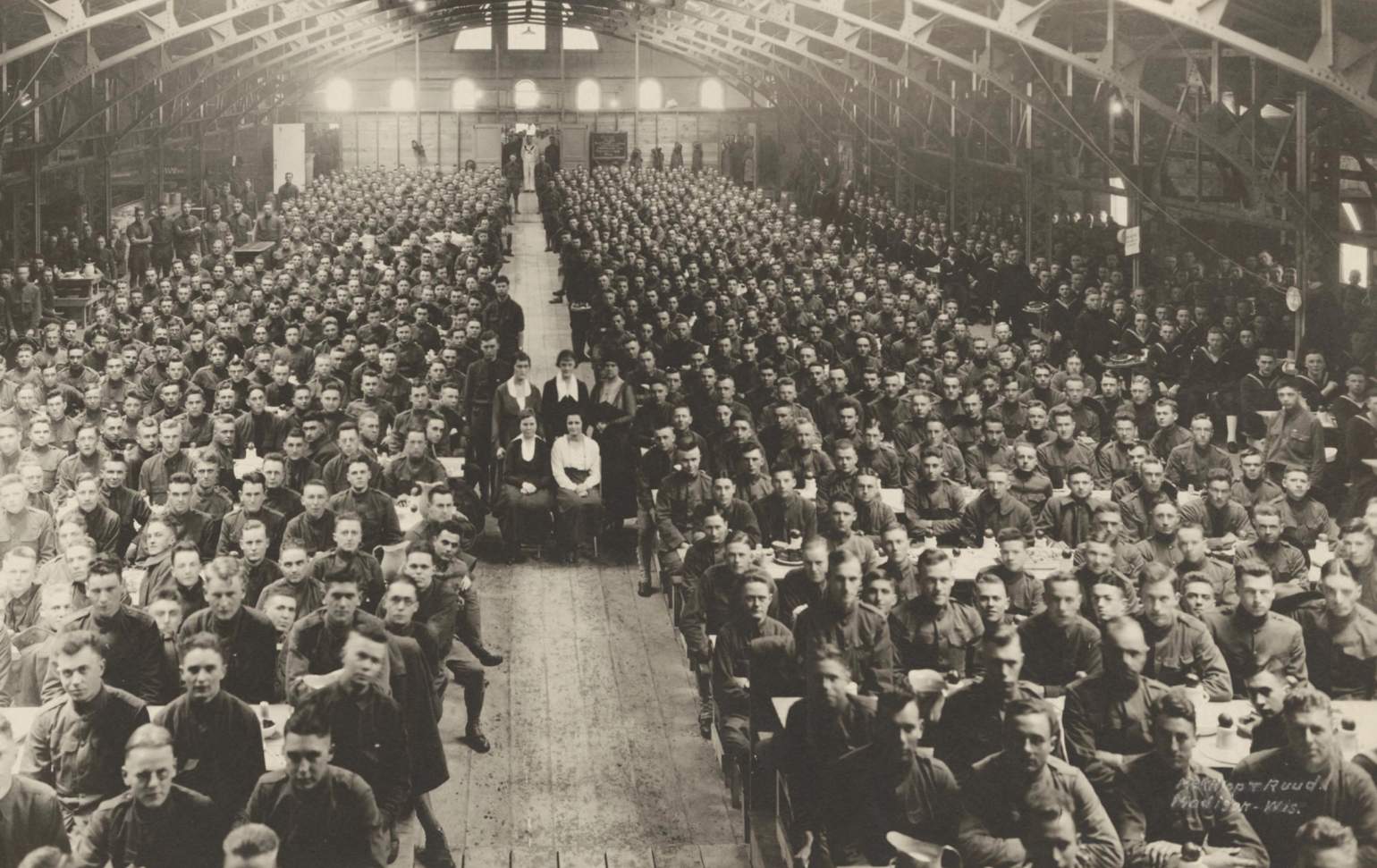

November brought reprieve to the ailing student body, as an armistice in the Great War was signed on Nov. 11, and the wave of influenza cases subsided. Classes resumed, and the men of the SATC crowded onto benches in the armory to share a Thanksgiving dinner. According to Oreck, this quick return to normal activity enabled a second and later third wave of influenza infections to plague UW-Madison and the surrounding city in subsequent weeks and months, a trend that was seen around the state and across the nation.

The final death toll in Madison and among SATC students is difficult to calculate, Oreck said, in part due to censorship and a lack of transparency from the U.S. War Department. As many as 328 influenza-related deaths were reported in Dane County in 1918, and campus officials acknowledged at least 39 student deaths in a June 1919 report, 36 of them SATC recruits.

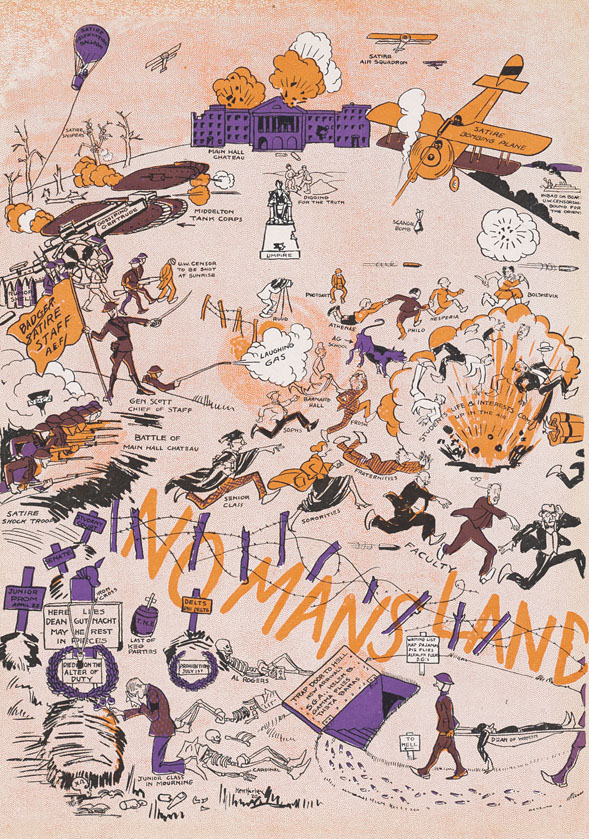

Despite the considerable impact of the pandemic at UW-Madison, little was done to memorialize the students who perished from the disease or note the historic nature of the events, Oreck observed. The SATC recruits who died during training are not among the honored dead listed in The Liberty Badger 1919 yearbook or the Gold Star Honor Roll, to whom the UW’s Memorial Union was dedicated in 1927.

“At the University Club, there is no plaque or memorial to note that that facility was an infirmary for hundreds of young men and not a few deaths during the epidemic,” Oreck said. “To the students and faculty of UW today, the UW of fall 1918 would be an incomprehensible foreign country.”

Key facts

- The Student Army Training Corp was a program of instruction with coursework provided directly from the U.S. War Department, including a minimum of 13 hours per week of military activities like drilling, inspections and theoretical military instruction. SATC students received further instruction based on the branch of military service in which they were preparing to serve. In addition to the regular students enrolled at UW-Madison in the SATC, the program also included vocational students who trained for enlisted technical specialties.

- While the 1918 influenza pandemic is sometimes called the “Spanish Flu,” research suggests the pathogen originated in rural Kansas in the spring of 1918 and was carried to Europe by U.S. servicemen fighting in World War I. Many of the nations hit by the virus were fighting in the war and suppressed public reporting on the outbreak, but Spain was neutral and did not censor its press in the same way, leading to the widespread and false assumption that it was the source of the illness.

- On Oct. 10, 1918, Wisconsin’s state health officer issued an order closing all public gathering places, such as theaters, saloons, schools and churches. The order also banned all large public gatherings, including many classes at UW-Madison. The state government did not have authority over the SATC, though, so training and classes pertaining to that program continued.

- Out of 943 reported cases among the SATC students there were 16 deaths, representing 26% percent of the program, not including vocational students who arrived on campus in late October. The case fatality rate was around 1.7% in this group. There were an estimated 270 cases identified in female students, or 15% of their enrollment, and one death, an estimated fatality rate of around 0.4%.

- Lieutenant E.S. Epstein, United States Army provost marshal of the SATC unit, penned a letter to Madison newspapers on Oct. 12, 1918, informing them that “The War Department has ordered the provost marshal to stop publication of all SATC news. Nothing will be published about the influenza or anyone sick in the hospital unless approved by the commanding officer through the Intelligence office and the provost marshal. All newspapers violating the above rules are subject to imprisonment in the federal system.”

- Dr. Steven Oreck passed away in August 2019, less than a year after his presentation. He served in the U.S. Navy and Naval Reserves for 37 years, retiring with honors as a Captain. Oreck provided both oral histories about his service and military artifacts to the Wisconsin Veterans Museum. He graduated with a degree in history from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, earned his medical degree from Louisiana State University and worked as a hand surgeon for many years. After retiring from medicine, Oreck earned a master’s degree and pursued a doctorate in history at UW-Madison.

Key quotes

- On the spread of the flu on the UW-Madison campus: “As soon as school opened, the influenza hit. By October 1, Dr. Robert Van Valzah, the head of student health, had taken over the University Club to be an infirmary with a projected capacity of 150 patients. Simultaneously, there was a nursing shortage. All six of the regular nurses employed by UW for student health had joined the military. By October 3, there were at least 170 men in the infirmary, 20 over the planned capacity.”

- On the breadth of influenza infections in Madison: “The report of four to 5,000 cases in Madison on [Oct. 14] needs to be reemphasized because, in 1918, Madison had a permanent population of approximately 37,000 and Dane County 88,000. When one subtracts children and the elderly from the population numbers and estimates a certain number of convalescents, this left little more than half of the adult population available for full activity. In Madison, as in the rest of the country, military activity continued with little modification due to the epidemic.”

- On a gender disparity in influenza cases and deaths in the pandemic: “The fact that more SATC students became ill and died compared to the female undergraduates can be explained in several ways. The SATC men lived in crowded barracks conditions with little separation between the beds, and some of the newly constructed barracks were not as weatherproof or warm as they might have been. These living conditions were ideal for the spread of an airborne virus. In addition to being thrown together in close quarters, there was an influx of new and previously unexposed SATC students throughout this time period, providing a large cohort for new infections of any severity and keeping a large viral pool circulating. SATC students, even though drill had been modified, still marched in formation to and from class and in general were more exposed to unpleasant weather than the women.”

- On the exemption of the SATC from the state’s closure orders: “Restrictions and troop movements could never have been absolute. In any case, there would have been disease spread, but hopefully in a less explosive fashion. The experience of the SATC at UW [with] two drafts of new students in October and November resulted in significant numbers of new influenza cases clearly illustrates this point… The UW administration was operating under significant constraints. The majority of its students, the men of the SATC, were in the military and under military discipline. Even so, the university could have been more aggressive, closing all classes except for the SATC as opposed to only stopping large classes.”

- On the relationship between UW-Madison and the War Department: “From the very beginning of the epidemic, the university had been in almost constant contact with the Army through SATC staff with the Department of War. The tone of the contacts had been deferential, and is noted in the letter from Dr. Evans to the War Department concerning medical staffing, the leadership role was deferred to the military, matching actions to tone.”

- On wartime censorship during the 1918 flu pandemic: “This sort of proscriptive and general censorship by the military of civilian newspapers was unprecedented in any American conflict and was more severe and direct than wartime censorship would be in the future, World War II and beyond… The university had accepted the necessity of proscriptive censorship, an astounding occurrence. In fact, only a small proportion of the SATC deaths were reported in Madison papers after October 12. These were hospital or infirmary deaths that were public and could not be concealed.”

- On the magnitude of military restrictions in place during the 1918 pandemic: “Imagine if you will, 90% of the male students not simply in uniform but living in barracks on campus, marching to and from class under military discipline. For today’s campus, that would be over 15,000 men in uniform. Then imagine over the space of four to six weeks, 5,000 of these men becoming ill with a disease of unknown etiology for which there was no treatment or cure, and 150 to 250 of them die… In Madison, imagine military police on the street with authority not only over the SAT students and any other military, but also empowered to intervene against civilians. The staff of the military training unit has been given authority to censor the contents proactively of your morning newspaper and to be up to date, your television and your Facebook and your Twitter and your Instagram and whatever else you have on your phone. And the editorial staff members who do not comply will be imprisoned.”

- On the limited impact the 1918 flu pandemic had on historical memory: “Given how deeply the entire community was involved in one aspect or another of the epidemic, how could memory be so easily expunged? We also should ask, were such a pandemic to strike again, would we see the same community solidarity now that was seen in 1918? For the first question, I can only suggest… that there was simply not room for the dual traumas of World War I and the influenza epidemic to coexist in the common memory. Since the war ended in triumph, as opposed to the epidemic that ended in mere survival, people unconsciously decided to remember the one and forget the other. As to the second question, that cannot be answered now. We can hope that our society has not become so fragmented that we could not come together in the face of this invisible threat. There is no doubt that another great pandemic will occur. The only question is when, not if.”

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.