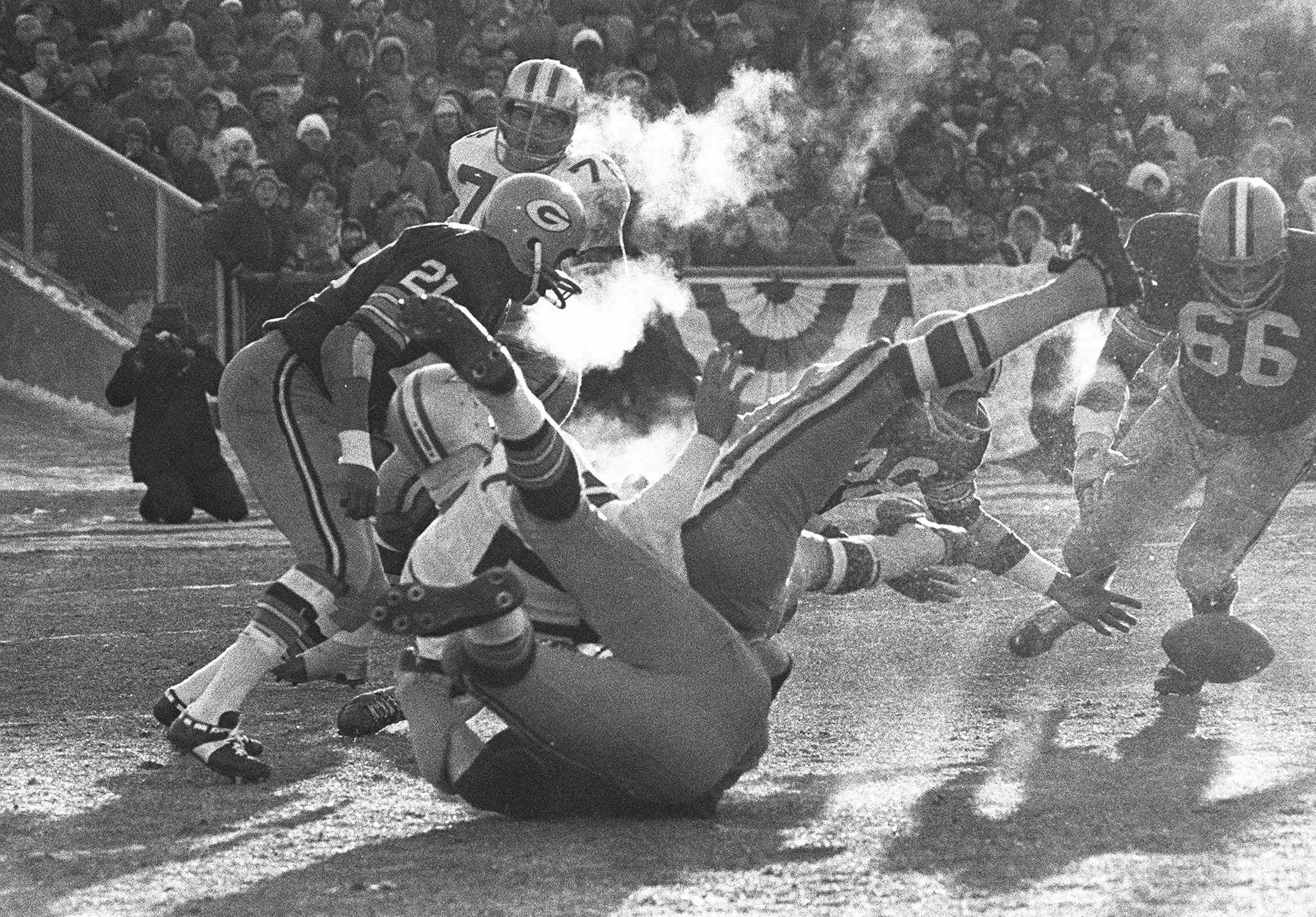

On New Year’s Eve 50 years ago, the Green Bay Packers faced the Dallas Cowboys at Lambeau Field in a playoff game that would come to be known as the Ice Bowl.

That Dec. 31, 1967 NFL Championship Game is on record as the coldest game in NFL history. With temperatures hovering around 13 degrees below zero, the Packers out-scored the Cowboys 21-17, claiming their third consecutive NFL title.

Cliff Christl, the Packers’ team historian, recalls the Ice Bowl as “a signature game in Packer history,” and so well-known because of the weather.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Thirteen below, minus 46 wind chill. Still the coldest game in NFL history,” Christl remembered.

Still, thousands of intrepid fans toughed out the conditions, sitting on freezing aluminum benches, because the game was a nail biter.

“It was the Packers’ third straight NFL Championship, something no other team had done under a playoff format and still something no other NFL team has done,” Christl said. “They beat Dallas on a quarterback sneak by Bart Starr with 13 seconds remaining in the game. Just a legendary drive under the conditions.”

According to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, the severe weather affected the Packers and the Cowboys alike.

Dallas scored a touchdown and a field goal after two Packer fumbles and added a second touchdown in the fourth quarter. Suddenly, with 4:50 left in the game the Packers were behind, 17-14.

With 16 seconds remaining and the temperature down to 18 below zero, the Packers found themselves about 2 feet away from victory. Starr called time out. The field was like a sheet of ice. The two previous running plays had gone nowhere. With no time outs left, a running play seemed totally out of the question. A completed pass surely would win it. Even an incomplete pass would at least stop the clock so the Packers could set up a field goal to tie the game and send it into overtime. After consulting with Packers coach Vince Lombardi, Starr returned to the huddle.

Starr took the snap from center Ken Bowman. Bowman and guard Jerry Kramer combined to take out Dallas tackle Jethro Pugh. With Pugh out of the way, Starr surprised everyone and dove over for the score. “We had run out of ideas,” Starr said of the play. However, Lombardi put it another way, “We gambled and we won.”

While the on-field action was exciting down to the last second, many NFL games end that way, Christl said, what still makes this game so compelling 50 years later are the conditions.

Gene Brusky is the science and operations officer for the National Weather Service in Green Bay. Like so many other Green Bay residents, he has a personal connection to the Ice Bowl. His father, Eugene Brusky Sr. was the Packers’ team physician who got the job after meeting coach Lombardi on a golf outing in 1965. Eugene Brusky treated players, including Starr, and referees for frostbite that day.

Gene Brusky said December 1967 started out fairly mild with temperatures mostly in the 20s.

“In the first half of December we had this split flow and that kept the cold air up in Canada, and we were under the influence of a subtropical jet which kept us milder.” But Gene Brusky said that was soon to change. “As we approached the last 12 days of the month, basically that’s where we got into that —if you want to use football jargon — the ‘second half adjustment.’”

One game, the American Football Conference Championship in 1981, gave the Ice Bowl a run for its money in claiming the “coldest game” title.

The game held in Cincinnati, between the Bengals and the San Diego Chargers boasted temperatures of 9 degrees below zero. San Diego lost that game known as the Freezer Bowl.

In 2001, the National Weather Service revised its wind chill index adding a “feels like” category. With those changes, the Ice Bowl’s “feels like” temperature would have been negative 48 degrees whereas the Freezer Bowl “feels like” temperature would have been negative 35.

Even though both games featured frigid temperatures, Gene Brusky points out that because Lambeau has a shallower stadium than the Bengals’ Paul Brown Stadium, fans and players at the Ice Bowl were more exposed to the cold northern winds.

The Frozen Tundra

The Ice Bowl would solidify Lambeau Field alias, the Frozen Tundra, partly because the ground actually froze.

Condensation built up and short-circuited the wires of the stadium’s underground heating system. As soon as the grounds crew removed the tarp from the field that Sunday, the field seized up, transforming into a sheet of ice.

The marching band from Wisconsin State University of La Crosse (now the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse) was unable to perform because their instruments froze or stuck to their lips. Referees had to deal with their whistles sticking to their lips. Fans who attended the game recall a fog spreading across the stadium after the winning play from the breath from shouting fans rushing the field to tear down the goal posts.

Christl suspects many parents decided they didn’t want to brave the cold and passed their tickets off to their kids, or neighbors.

“Back then it would not have been unusual for people to just give their tickets to their kids, maybe drop them off at the stadium and say, ‘Good luck,’” he said.

That is what happened to Wisconsin state Sen. Dave Hansen, D-Green Bay, who was there that day.

“It wasn’t something that we had planned for. I didn’t go out searching for tickets the day before, but when the neighbor came up with them and when you’re 20 years old?” He paid $12 for his ticket and ignored parental advice when it became apparent the game would be a chiller. “When my mother said, ‘You can’t go, it’s too cold’ I’m saying, ‘Hey $12 is $12,’” Hansen recalled.

Heeding his mother’s warning, Hansen bundled up, wearing “insulated underwear, blue jeans, a couple pairs of pants, several shirts, scarves for sure, and a good heavy hat,” he said.

In bipartisan fashion, Hansen gave a nod to the losing team, coached by Tom Landry.

“It does say something about the Cowboys that they were able to compete in such a way; and I give them a lot of credit you know, coming from down south,” Hansen said.

In 1967 Lambeau Field had a capacity of 50,837 people. While many more than that claim they attended the Ice Bowl, Hansen has the proof.

Hansen still has a dog eared program from the game and he said, “a million people said they were there, but I was there, and I have the frostbite to prove it.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.