Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison are part of an international team working to understand the discovery of an ancient burial site created by early human ancestors.

UW-Madison anthropology professor John Hawks was part of the group that first found the bones in the Rising Star cave system in South Africa in 2013. The team, led by paleoanthropologist Lee Berger from Johannesburg, first published the discovery in 2015. They released three new scientific papers this week detailing what they’ve discovered about the two locations of remains within the narrow passages of the caves.

“We’ve been working on the site for the last decade and it’s been an amazing journey,” Hawks said. “We’ve got really interesting fossil material of this new species, Homo naledi, dispersed in different parts of a deep underground cave system. And we’ve been trying to understand how they got there and how they were using this cave system.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

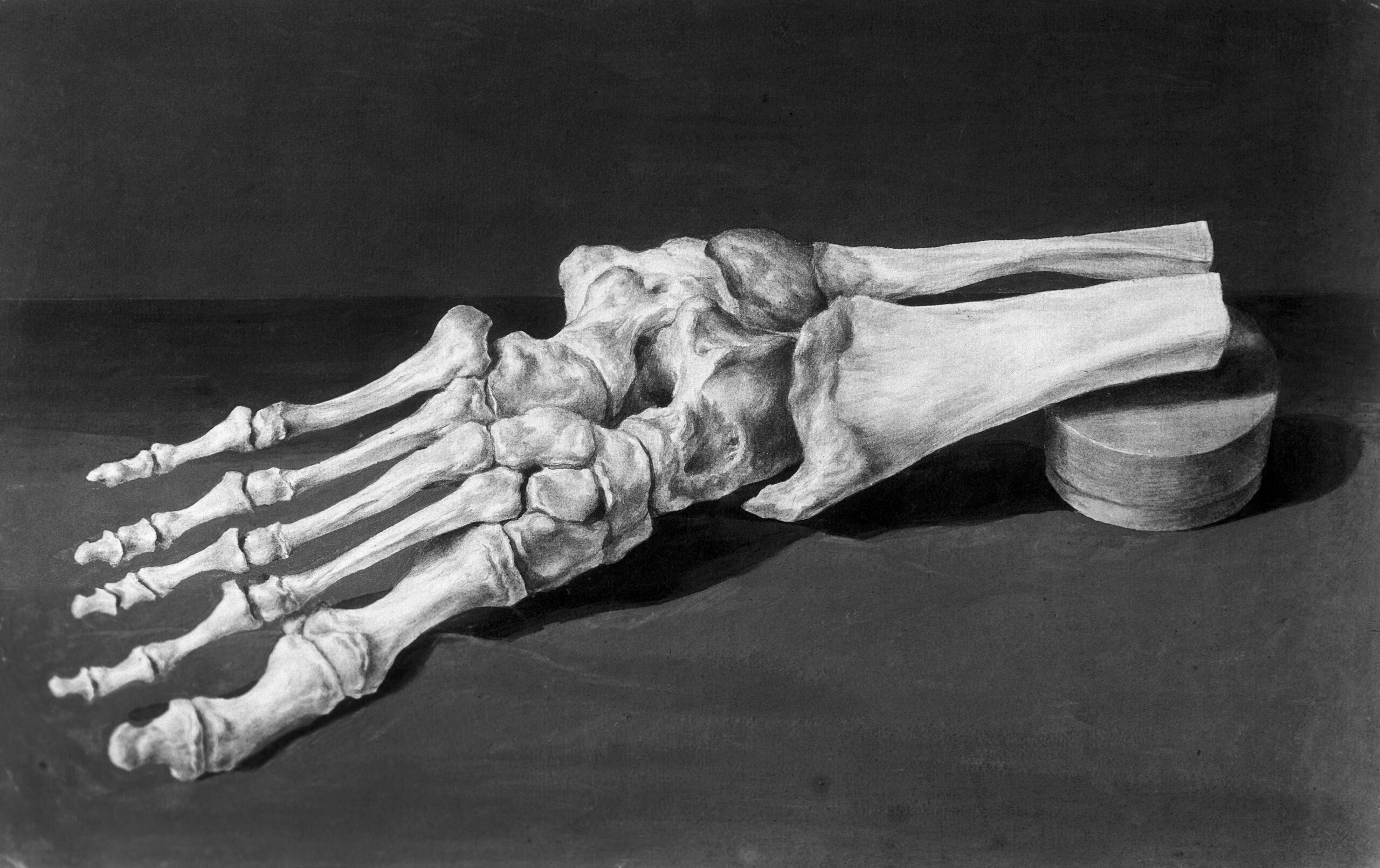

Living between 335 and 241,000 years ago, Homo naledi existed around the same time as the earliest Homo sapiens relatives. Hawks said their skeletons reveal characteristics that are similar to humans, such as their teeth, feet and lower legs. But other parts of their skull and anatomy resemble more ancient species, sparking questions around where Homo naledi fall in the family tree of early humans.

Hawks said the research team found evidence these early humans chose to bury their dead in the caves. Instead of evenly-distributed sediment layers like much of the cave floor, the sediment under the bodies was disturbed, indicating that the early ancestors dug the graves.

“Its brain is about a third of the size of today’s people. So what we’re finding is challenging the view that brain size is really the important aspect of our evolution,” he said. “It may be that our ability to cooperate culturally doesn’t depend strongly on brain size but that it enables us to adapt to different environments.”

Hawks said it’s difficult to determine scientifically what Homo naledi’s motivations for burying their dead were. He said it’s possible their reasons are very different from the cultural or religious traditions of burial seen in today’s humans. But Hawks said the existence of some kind of burial tradition in itself is significant for understanding ancient human social systems.

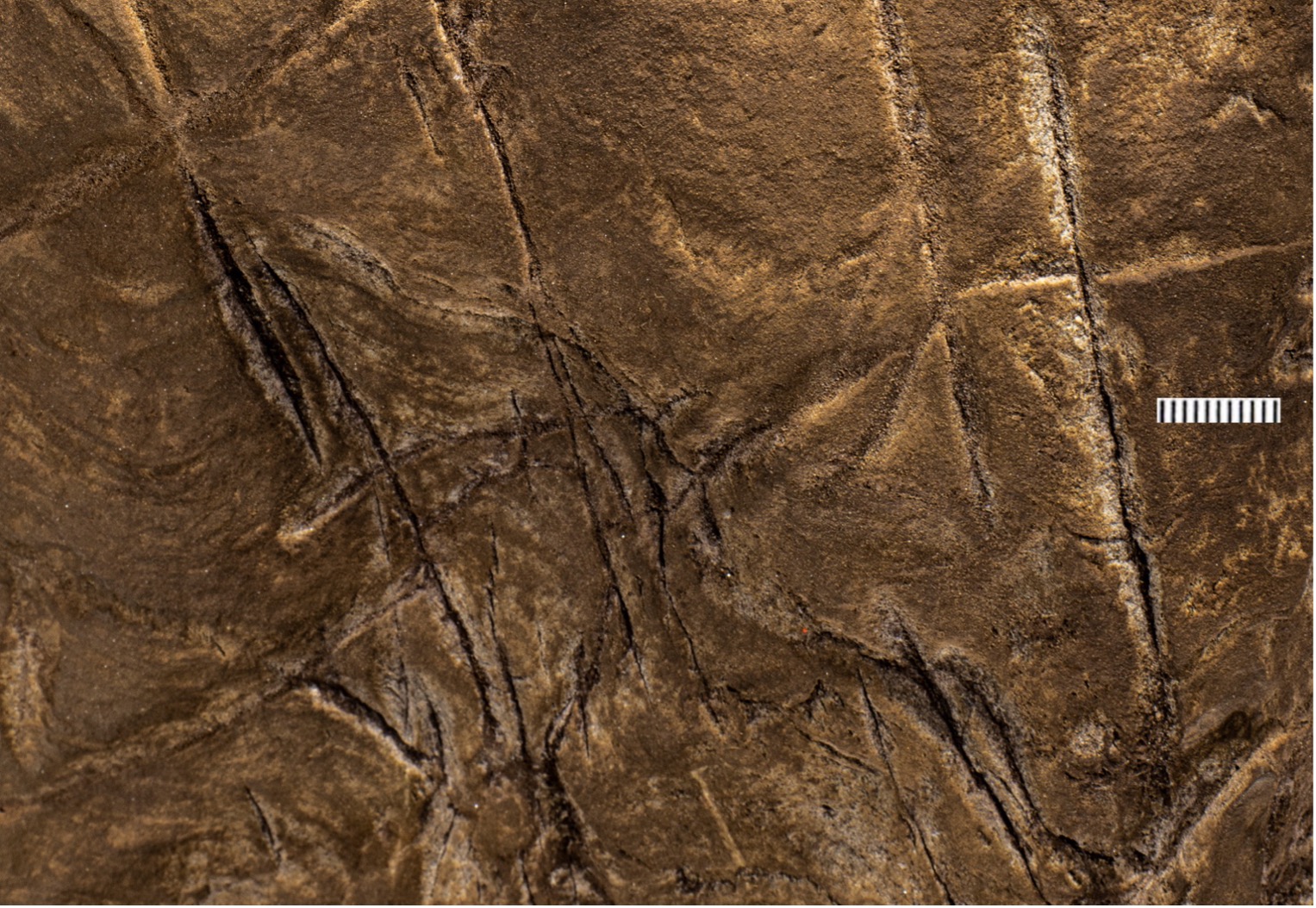

The research team also discovered markings on the cave walls near the bodies last year. Hawks said they’ve found no other species in the cave system and the difficult-to-reach location of the scratch marks points to our better-climbing ancestors.

“I can’t go to this place, it has tremendous physical challenge in terms of climbing down a very, very narrow passage. And so that puts it in a very interesting situation,” he said,

The markings are not cave art representing images, but crosshatch markings that appear to have been made with some type of tool. Hawks said it will likely take a long time for researchers to study and understand them, but their existence will help build out the broader understanding of Homo naledi.

“We have an opportunity to understand the way that an ancient relative of ours, who is very different from us, was using an extreme environment,” he said. “We’re still working out how to encounter the different kinds of evidence that are there and integrate them together into a picture of ancient behavior.”

Erica Noble is one of two doctoral students at UW-Madison who joined Hawks in working at the Rising Star cave system last summer. Noble, whose anthropology work focuses on the development of the scapula in humans, said it was a 10-minute journey into the caves before reaching their work site.

“It’s definitely not your typical sort of archeological site when you think of people doing fieldwork,” she said. “It is a cave system made up of multiple different chambers, connected by passages that can get pretty tight at times, and that sort of spans this hill.”

While Hawks and Berger’s discoveries still need to be peer-reviewed, Noble said the discoveries could challenge the idea that complex behavior is unique to modern humans. And the work in South Africa is far from finished.

“Every time, it seems, we go down into Rising Star, we find new and exciting things,” she said. “Sort of the thought process behind announcing these things now instead of waiting for multiple years is that these are interesting findings, and we don’t want to be sitting on them.”

Hawks said the team will continue to test evidence from the cave to help verify what they’ve found, while working through the large number of questions raised by other anthropologists.

“We have so much left to learn about our origins and about the relatives of ours that once existed,” he said. “The world was more interesting in the past than we knew.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.