Driving along Winnegamie Drive in Appleton, one can see a large, yellow-painted rock on the side of the road — and then another, and another.

The continuous line of rocks is what first made resident Beth English interested in the Yellowstone Trail.

“I assumed they were advertising for a campground in the area and not that they were anything special,” she said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

She soon learned the rocks were used to mark the Yellowstone Trail, the first transcontinental highway to travel through the northern tier of the United States. But she wanted to learn more about its history and its path, so she turned to Wisconsin Public Radio’s WHYsconsin for help.

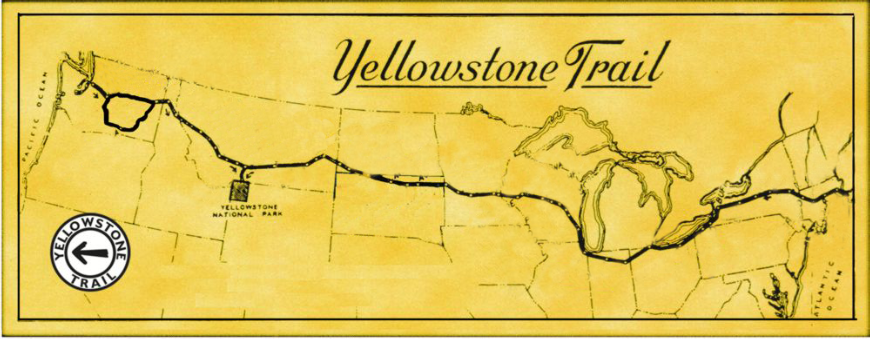

The short answer to one of English’s questions is that the roadway travels through 13 states with termini in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and Puget Sound, Washington. A portion of it goes through 61 Wisconsin towns and cities.

For Altoona couple John and Alice Ridge, there is a deeper story behind this highway that’s thousands of miles long. They’ve driven the entire trail multiple times.

“Taking a train, you may catch glimpses of things, but when you’re traveling with a car and you’re camping, you meet people — you talk with them,” John said. “It was kind of a revolution.”

A brief history of the ‘good road’

Efficient long-distant roads and government-marked routes were nonexistent in the early 1900s, according to the Yellowstone Trail Association website.

As the automobile became a popular form of transportation, the need grew for better, and more, roads.

A man named J.W. Parmley initially wanted to construct a “good road” in South Dakota, where he lived. In 1912, the original plan was for the road to stretch from Ipswich to Aberdeen, but the road’s path quickly grew, according to the website.

Parmley and his colleagues planned to extend the route to Mobridge, South Dakota, then to Hettinger, North Dakota — and then to one of the top tourist destinations at the time: Yellowstone National Park. Soon, the group decided the road should go across America, connecting the West and East coasts.

“It was only natural,” John said, for the group to call the route “Yellowstone Trail” because the name would encourage tourists to travel to Yellowstone National Park.

Parmley and his colleagues formed the Yellowstone Trail Association, an organization that encouraged cross-country travel by vehicle, provided the first maps of the road and marked its route.

In 1912, highways weren’t numbered, so association members and volunteers painted rocks yellow and put up yellow signs with an arrow and the words “Yellowstone Trail” to direct tourists toward the roadway. While not super close together, yellow rocks sat along most portions of the entire trail.

The Ridges believe there are only two original yellow-painted rocks left. In 1926, the American Association of State Highway Officials numbered interstate routes, so the need for the yellow rocks ended.

The original Yellowstone Trail Association ceased to exist in the 1930s as tourists began to gravitate toward more modern highways. But in 1999, the Ridges, local historians, university professors and tourism officials joined together to create a modern Yellowstone Trail Association.

The Ridges and other members of the current association started “to spread the word,” according to the website, about the trail’s historical significance and tourism potential.

Researching the Yellowstone Trail

The Ridges have been researching the Yellowstone Trail for 25 years.

Years ago, John’s father, Harvey, had talked to the couple about the “strange yellow stones” he’d seen in the past when driving along the Yellowstone Trail near Eau Claire.

At the time, John and Alice were professors at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. Though neither of them taught history, they started traveling along the highway once they retired.

They “lived” out of libraries and museums, analyzing old newspapers and maps in an effort to trace the route and its history.

All of this research led them to publish a book last fall titled “A Good Road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound, A Modern Guide to Driving the Historic Yellowstone Trail, 1912-1930.”

People whose parents and grandparents drove the highway are getting older and dying, John said. This makes preserving the history of the roadway more crucial.

“It’s, in many places, still just a forgotten bit of history,” he said. “But we’re doing our best to make it known.”

The Ridges have connected with several Wisconsin communities the trail passes through, as well as other states along the route, to tell them about the highway.

Celebrating history

Jacki Bradham, of Hudson, had never heard of the Yellowstone Trail until the Ridges contacted the Hudson Area Chamber of Commerce and Tourism Bureau in 2010.

The Hudson Toll Bridge played a key role in the trail, allowing tourists to cross the St. Croix River, travel through the Twin Cities and continue westward.

“If another community had had a bridge that was close to the Twin Cities, it (the Yellowstone Trail) probably could have taken a totally different route,” Bradham said.

Upon learning about the trail’s significance to the city, Hudson created their annual Yellowstone Trail Heritage Day, and Bradham, a member of the Yellowstone Trail Committee, helps plan the event.

They host car shows and beckon hundreds of people to check out a display of vintage automobiles that would have been used on the trail. This year, the event was held Aug. 13 and encouraged people to take scenic drives along a portion of the road.

Bradham said this year’s event also included a demonstration of popular dances from the early 1900s and a book-signing with the Ridges.

Over the last several years, Bradham said popularity in the Heritage Day event has steadily increased, and she finds her own passion for the trail’s history continuing to grow.

“The more you learn, the more interesting it becomes,” she said.

The Ridges said there are similar celebrations in Indiana, Idaho and South Dakota to commemorate their portions of the trail.

There are about 200 members in the Yellowstone Trail Association to this day. Owen, Stanley, Appleton and Chippewa Falls are some Wisconsin cities that have more recently placed yellow-painted rocks along the route.

John and Alice Ridge hope to “retire again” after decades of researching the trail. But in reflecting on the many times they’ve traveled on this historical route, they said there is much to appreciate.

“It’s hard picking out one spot or one group or one culture that was more interesting than another,” Alice said. “I think what was most valuable to us was the people that we met.”

This story was inspired by a question shared with WHYsconsin. Submit your question below or at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it.