Wisconsin entered the Union as a free state in 1848, and has its share of associations with the abolitionist movement — the state Supreme Court, in what is among its most significant decisions, declared the federal Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional in 1854, and opposition to slavery drove the genesis of the Republican Party in Ripon the same year. But slavery was present in pre-statehood Wisconsin, and the institution writ large shaped attitudes that would impede efforts by African-Americans in the state to secure their right to vote.

Understanding the history of black suffrage in Wisconsin requires reaching back to its days as part of the Northwest Territory and unpacking the little-discussed role of slavery in the Upper Midwest, Christy Clark-Pujara, University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of Afro-American studies, explained in a Feb. 20, 2018, talk at the Wisconsin Historical Museum. On the day of the talk, which was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s “University Place,” voters were casting ballots in a spring primary election.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Clark-Pujara discussed how French fur traders first brought enslaved African-Americans to the Midwest, and how the practice of slavery continued after the American Revolution, even though it was officially made illegal by the Northwest Ordinance. Of course, to tell this story is to push back on a misperception of slavery as an exclusively or even primarily southern institution.

“It was not — it was a national institution sanctioned and protected by the entire country,” Clark-Pujara said. “Moreover, white Americans, North and South, were deeply invested in the business of slavery.”

The debate over voting rights even delayed Wisconsin’s bid for statehood by a couple of years.

An early version of Wisconsin’s state constitution, in 1846, would have let the new state’s voters decide via referendum whether black men should be allowed to vote. But for this and other reasons, including provisions providing property rights for married women, this version of the constitution was scrapped. Those opposing the black male suffrage provision advanced overtly racist arguments.

The state constitution Wisconsin adopted in 1848 barred black people from voting, but did grant it to white men regardless of their citizenship status — like newly arrived immigrants — and to Native American men who renounced tribal affiliations. This created a political structure in which, as Clark-Pujara put it, “you didn’t need citizenship, you just needed whiteness.”

After statehood, debate over slavery, race and suffrage continued, and shaped an incongruous racial politics. “In the mid-19th century, fugitive slaves passing through Wisconsin were often met with assistance, while black permanent residents were marginalized,” Clark-Pujara said.

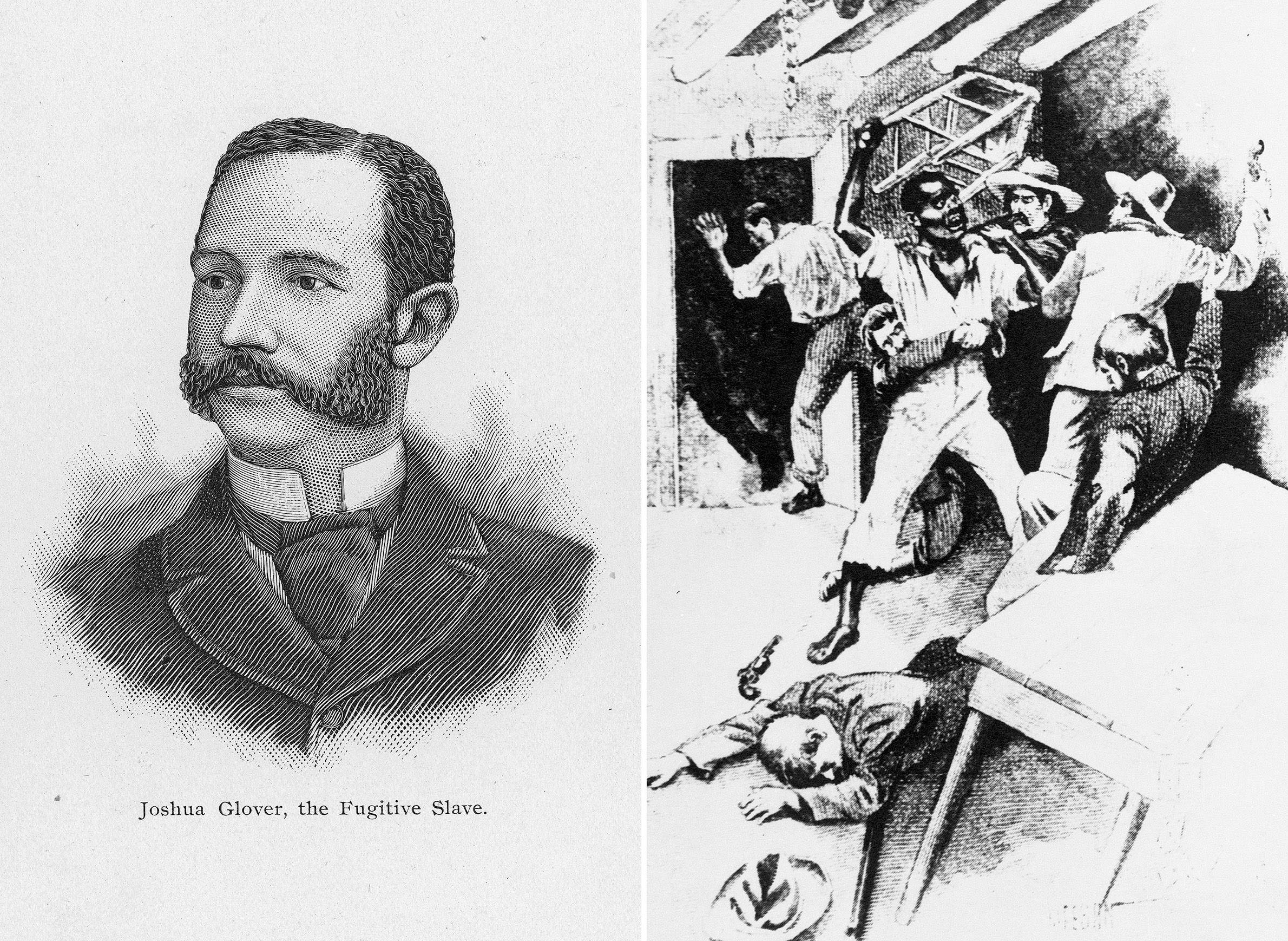

While many white citizens in the young state of Wisconsin opposed slavery, most of those people were not actively working to abolish it, and many feared black migration into the state. Abolitionists in Milwaukee played a celebrated role in the escape of a fugitive slave from Missouri named Joshua Glover in 1854, and the state Supreme Court officially sanctioned abolitionists’ efforts to harbor escaped slaves that year.

But many Wisconsinites were far from ready to embrace African-Americans as full citizens and black men did not gain the right to vote in the state for another dozen years, after the Civil War had ended.

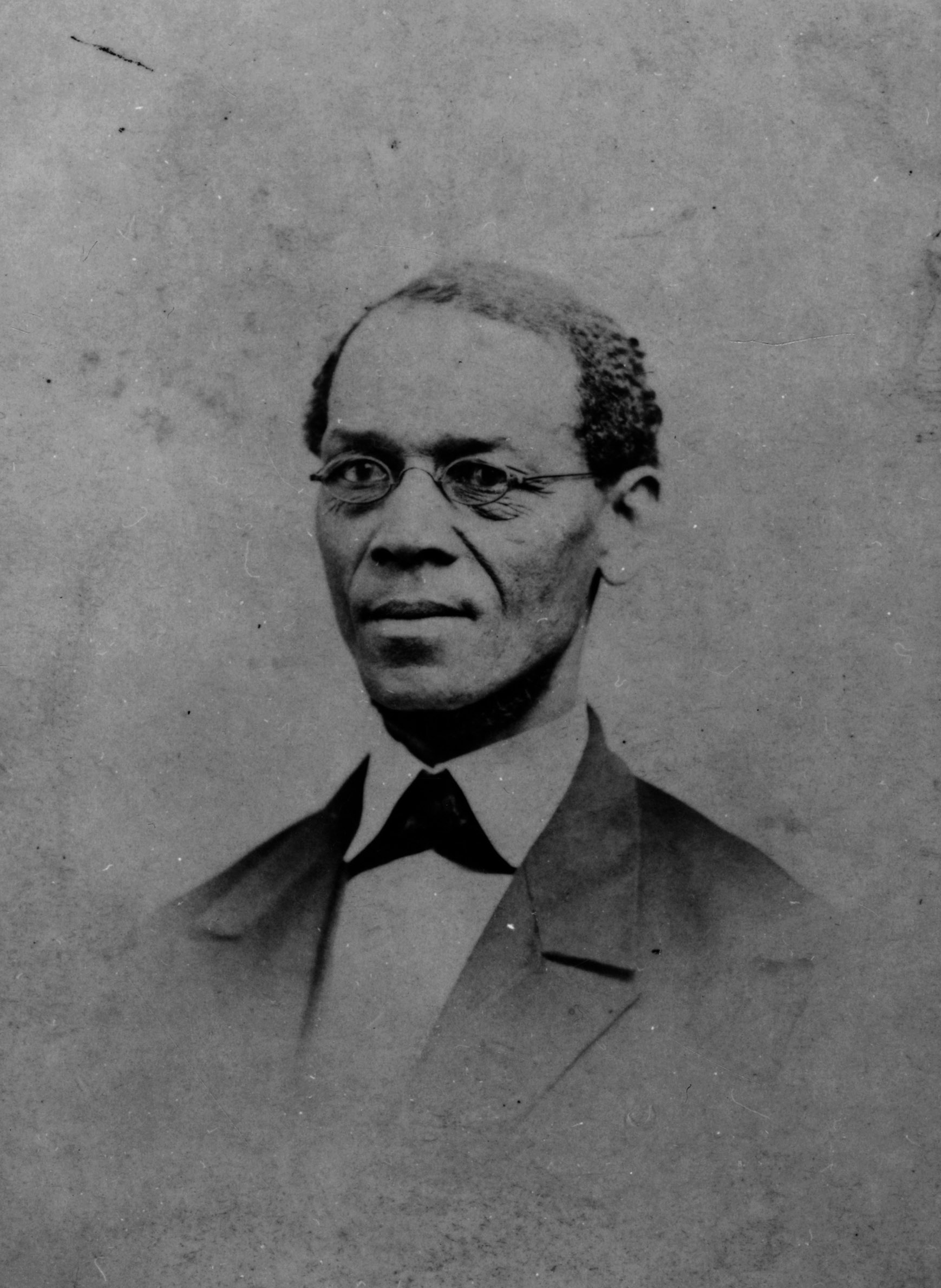

One black Milwaukee resident who had been active in the Underground Railroad, Ezekiel Gillespie, sued the state after he attempted to vote in an 1865 referendum on black male suffrage and was turned away. In 1866, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in Gillespie’s favor, establishing the vote for black men in the state.

Wisconsin wasn’t technically the first state to allow African-Americans the vote, though it was the first Midwestern state to adopt black male suffrage without restriction. As of 1830, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont had black suffrage, according to the book “In Hope Of Liberty,” by historians James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton. At that time before the Civil War, the state of New York allowed black men who owned property to vote, but didn’t have property restrictions for white voters. By 1860, biracial men who were at least half white were allowed to vote in Ohio, and in Cincinnati, black men could vote for school board candidates, but only those serving segregated schools. And by 1860, Michigan allowed black men to vote in school board elections

Moreover, during the period between the American Revolution and the 1870 ratification of the 15th Amendment, not all gains in black suffrage were permanent. Several states, including Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, initially allowed black men to vote, but rescinded their franchise at different points during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Even after black people had the legal right to vote, state and local officials would interfere with tactics including poll taxes, literacy tests and direct intimidation.

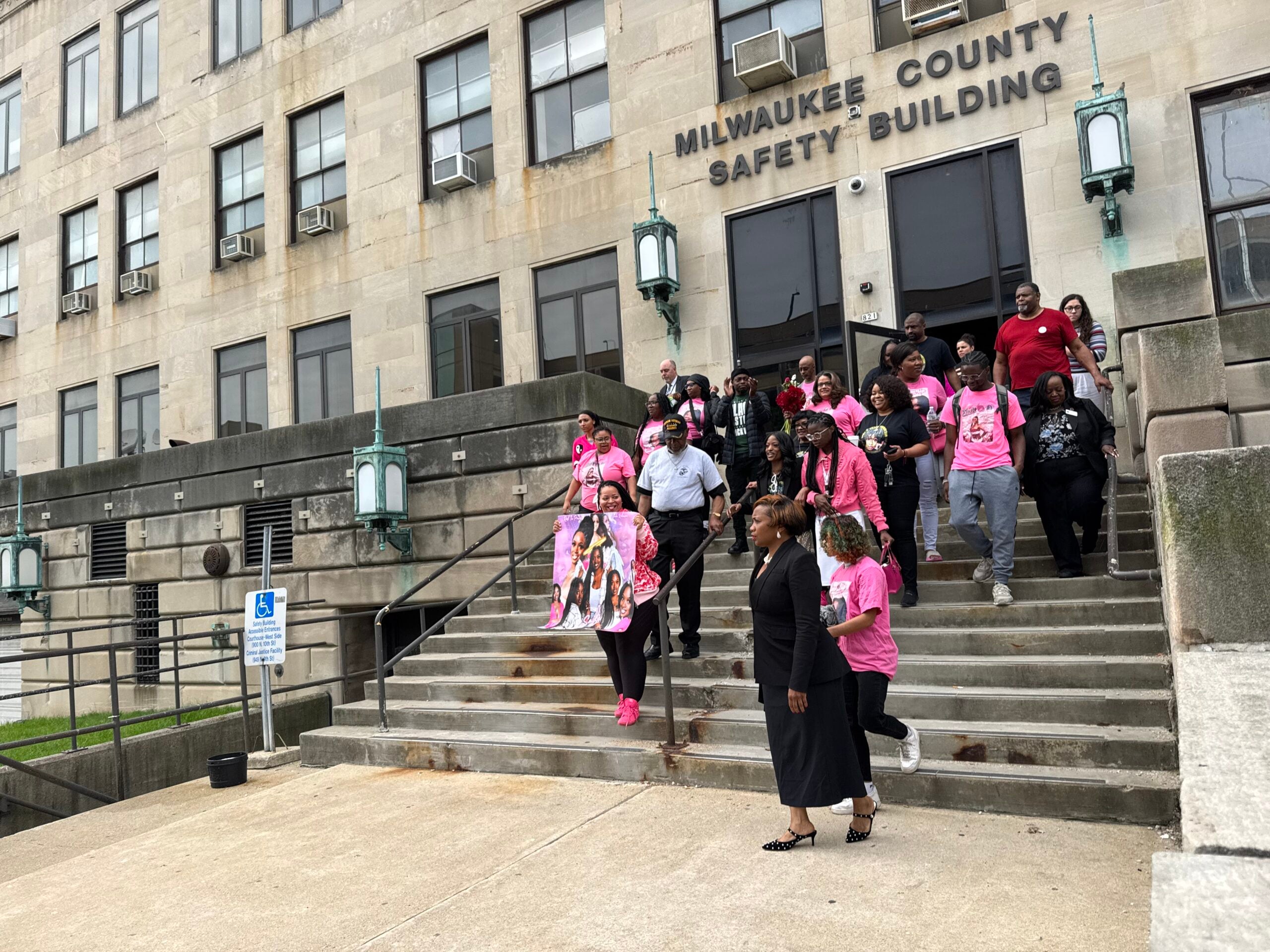

Debates over enfranchisement and citizenship continue in the 21st century: Wisconsin is enforcing a voter ID law that has been found to disproportionately impede non-white voters and the state has some of the worst racial disparities in the nation.

Imbalances in voting rights continue to resonate, Clark-Pujara said.

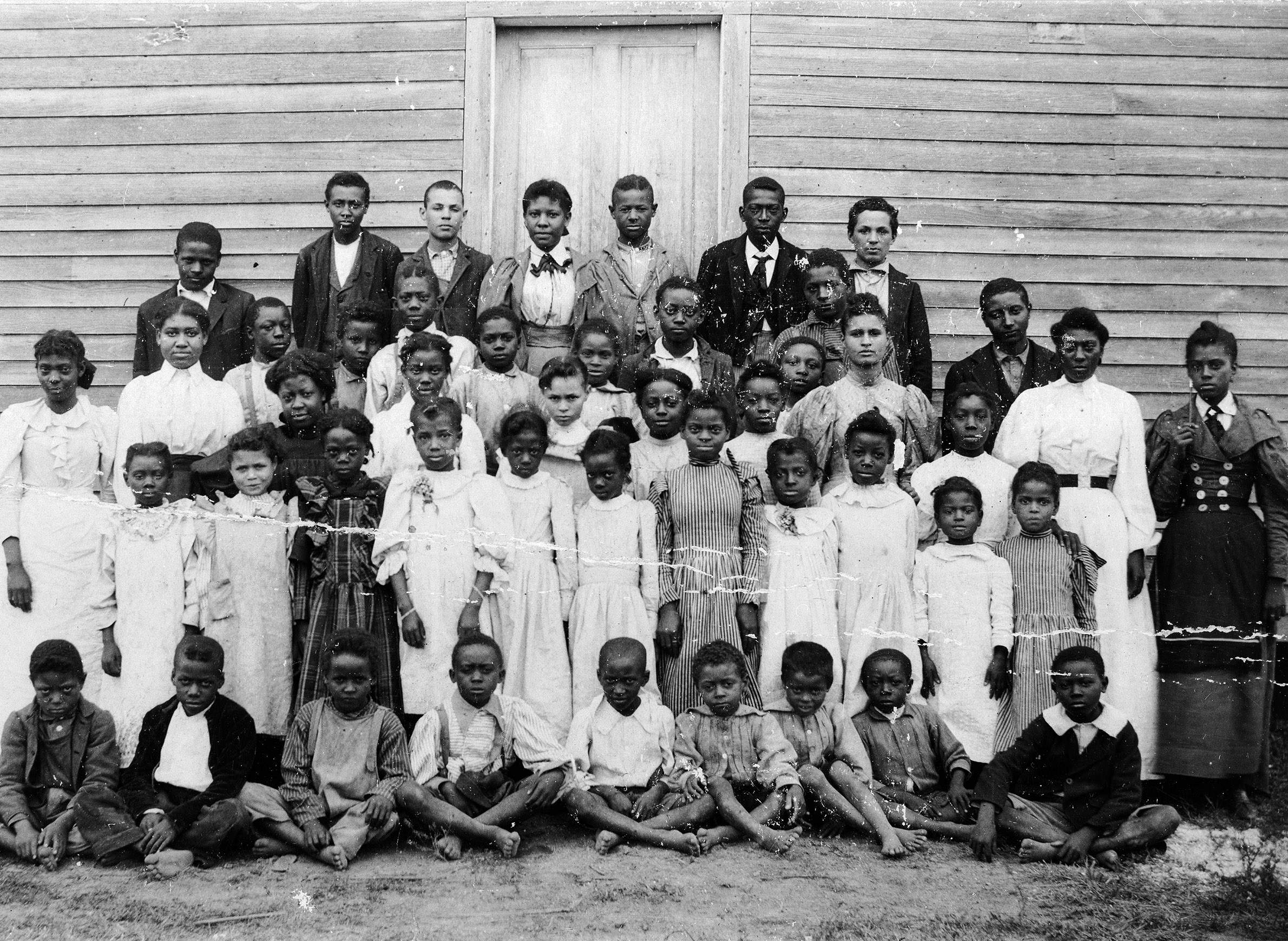

“Suffrage in a new state meant more than political power. It provided an opportunity to shape state institutions and society at large,” she said. “For 17 years, black men in Wisconsin were barred from the ballot box, and their disenfranchisement excluded them from shaping the state’s public institutions.”

Key facts

- African-Americans first came into the Midwest in the 1720s, primarily as slaves of French fur traders, though some were free. By 1752, 446 enslaved black people lived in the region.

- The Northwest Ordinance, passed in 1787, officially banned slavery in the Northwest Territory, but it continued in the region until the late 1840s. There was no enforcement mechanism for the slavery ban, and the practice of indentured servitude was one way people circumvented the law. When parts of the Territory became states — like Ohio in 1803 and Illinois in 1818 — it tended to force the issue of slavery upon entry into the Union. Wisconsin became a state in 1848.

- The military was another hole in the slavery ban, as officers in the U.S. Army were allowed to use slave labor. Between the 1820s and 1840s, officers brought slaves to work at military installations in what would become Wisconsin, including Fort Crawford in Prairie du Chien and Fort Winnebago in Columbia County.

- Lead miners like Henry Dodge — who later became the first territorial governor of Wisconsin and one of Wisconsin’s first two senators after statehood — were big drivers of slavery in the region. Dodge was among those who flouted the Northwest Ordinance’s prohibitions on slavery with impunity. Five of the slaves he brought to Wisconsin — known only as Toby, Tom, Lear, Jim, and Joe, as their surnames were never recorded — remained in bondage under Dodge for 12 years, though he had initially promised to free them after six months of servitude.

- Paul Jones, an enslaved lead worker in Sinsinawa in what is now Grant County, sued for back wages in 1846, but a court ruled in favor of his enslaver, George Jones. The case is relatively obscure, but similar argument was made in in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, which declared that black people in the United States had no standing to sue in federal court. Jones and other emancipated black people, as well as escaped slaves, populated Pleasant Ridge, a free black community founded in 1848 in Iowa County. Pleasant Ridge is now one of southern Wisconsin’s ghost towns.

- Wisconsin held a referendum on black male suffrage in 1849, and the majority of those who voted supported approval. However, more than 31,000 eligible voters didn’t vote on the referendum at all, and the state counted their abstentions as votes against black suffrage.

- The nascent Republican Party added universal male suffrage to its party platform in 1855, but dropped the plank in 1857 amid a lack of popular support. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party adopted positions staunchly opposing black suffrage or equality between the races.

- Wisconsin held a second referendum on black male suffrage in 1857, which failed by a broad margin, 45,157 votes against and 31,964 in favor.

- Wisconsin’s African-American community actively worked for the right to vote in the state’s early years. In the wake of the Republican Party’s 1855 declaration in support of universal male suffrage, black activists held a meeting in Milwaukee to adopt a resolution of support for the party, and even raised money to print that meeting’s proceedings in local newspapers in order to create a record. After the 1857 referendum failed, black Wisconsinites continued to press the issue through mass meetings, petitions, and simply showing up to the polls.

- The state Supreme Court’s reasoning in its unanimous decision in Gillespie vs. Palmer, which granted black Wisconsinites the right to vote in 1866, was that the 1849 referendum should have been counted as a yes vote, and that the state erred in counting non-voters as no voters.

- Women of all races in Wisconsin were not able to vote until the adoption of the 19th Amendment in 1920. In 1884, the state’s women’s suffrage movement won a short-lived victory, when the state Legislature granted women the right to vote, but only for education-related candidates. But the state Supreme Court put a stop to that in 1888. A 1911 state referendum on granting women the vote failed.

Key quotes

- On slavery in the Northwest Territory: “In the North, you would often get 40-42 percent of white heads of households owning people. They usually owned one or two. In the South, you had about 24 percent of the population holding slaves, and they usually held five or more, planters 20 or more. So the patterns of slave ownership were different, but slave ownership was more widespread in the North than it was in the South, even though you have higher concentrations of enslaved people in the South.”

- On the use of indentured servitude in the Northwest Territory: “Most historians of slavery in the Midwest just talk about them as being a form of slavery. Because some were 30 years, some were 60 years, and there were 99-year indentures. If you are indentured for 99 years in the 1830s, that is slavery, right? And the rules and regulations that applied to people, things like, you couldn’t go more than a mile from where you were bound without a pass. It very mimicked slavery.”

- On the role of slavery in the Midwest: “Enslaved people were present in every facet of the economy. They labored on farms, in the skilled trades, as domestics and miners. It was a fluid institution. In the Midwest, slavery was openly practiced, but it was rarely acknowledged. It was a fluid institution, taking on a variety of forms including open and legally sanctioned slavery, long-term indentured servitude, adoptions that were intended to mask child slavery and outright illegal slaveholding.”

- On the importance of referring to individual slaves by name: “If you noticed, I said their names a lot: Toby, Tom, Lear, Jim, and Joe. And I referred to Henry Dodge as just Henry. This is intentional. We know who Henry Dodge is. We don’t know about the bound laborers that created his wealth, that built that mine, that worked that mine. And we don’t have surnames for them. And so when I can’t speak their surname, I will not speak his surname.”

- On the small numbers and large significance of slavery in Wisconsin: “Overall, Wisconsinites held very few slaves. By 1840, only 11 of the 196 black people in the Wisconsin Territory were enslaved. Nevertheless, the existence and the practice of race-based slavery in Wisconsin shaped white attitudes about African Americans, because they, like the rest of white Americans, associated slavery with blackness, the antithesis of citizenship. Race informed evolving definitions of citizenship and worthy settlement.”

- On one reason Wisconsin’s proposed 1846 constitution failed: “The debate over black suffrage during the 1846 constitutional convention revealed overt racism among some leaders in the territorial government. They claimed that God sanctioned the separation of races and describe black men as ‘thieves’ and black women as ‘far worse’ than thieves. These are direct quotes. They also argued that the people of Wisconsin would not accept black male suffrage, and I quote, ‘The people would deem it an infringement upon their natural rights thus to place them on an equality with the colored race.’ First, who are you determining to be people? People and whiteness are being equated.”

- On the significance of Wisconsin’s 1849 referendum on black male suffrage: “The apathy of tens of thousands of voters had serious consequences for free black people in the state of Wisconsin. This is also going to have consequences for free Asian people in the state of Wisconsin. And free Mexicans in the state of Wisconsin. Because whiteness is the bar, and Natives who cease to be Natives.”

- On the historical importance of the black experience in areas where African Americans were a tiny minority: “An absence of a large black populace did not meant that ideas of blackness and whiteness were not central to the social, political, and economic development of these places. This is especially relevant in the territories, when many white Northerners and Midwesterners claimed that their given locales were bastions of freedom because there were few or no black people. Enslaved and freed African Americans lived, labored, and raised families on the Wisconsin frontier. They called Prairie du Chien, Racine, Green Bay, Lancaster, Milwaukee, Madison and Menominee home. Yet their stories remain largely untold. The history of the state and the region remains incomplete without a full accounting of the African American experience and influence.”

Wisconsin’s Halting Path Towards Black Suffrage was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.