Cher Kai Xiong wasn’t nervous on his way in to meet former Vice President Joe Biden.

The 79-year-old was a captain in the Secret War, which in the 1960s and ’70s brought Hmong soldiers in Laos together with U.S. forces in an attempt to combat the rise of communism in Vietnam. Like tens of thousands of other Hmong refugees, Xiong came to the U.S. after the war, living in Kentucky and Indiana before settling in Green Bay. Today, one of his sons serves in the U.S. military.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

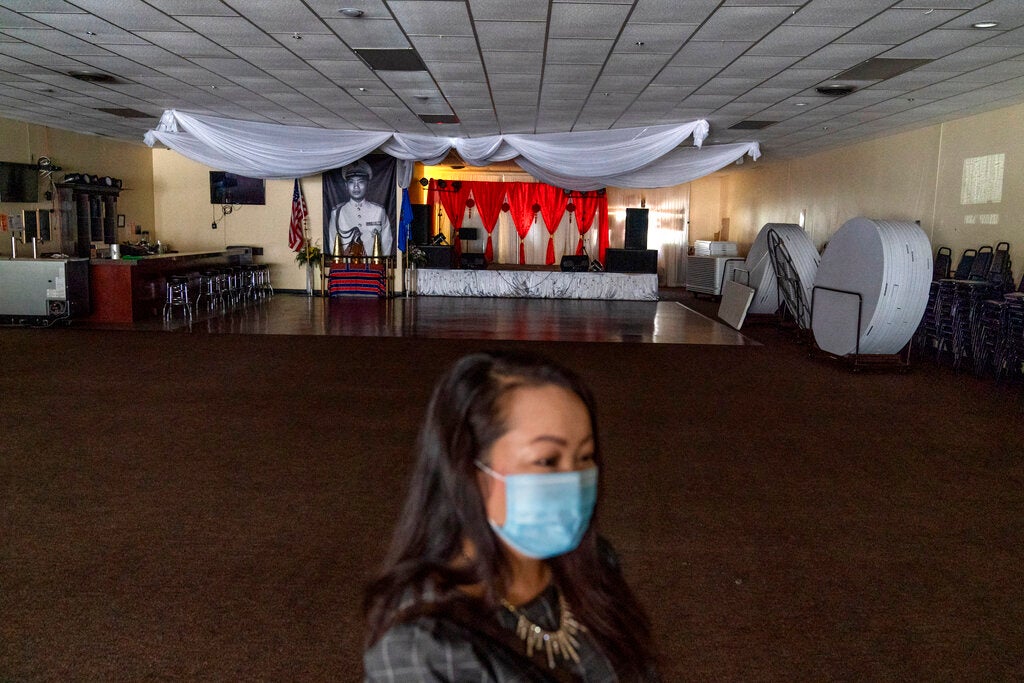

Xiong met Biden during the 2020 Democratic presidential nominee’s visit to Wisconsin in September. They spoke, masked and at a distance due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in a private meeting before Biden’s visit to Kenosha, where he held public events.

“I was very happy to have seen and met the vice president,” Xiong told WPR through an interpreter. “I was also happy to express and tell (Biden) to remember the contribution of the Hmong veterans.”

Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, left, meets with Hmong veteran Cher Kai Xiong, far right, and Yee Leng Xiong, who provided translation, Sept. 21, 2020 in Green Bay. Photo courtesy of Hmong Americans for Biden

It was a short meeting. But it was also a historic one. Biden told Xiong he would commit to remembering the sacrifices of the Hmong people on America’s behalf. It was an emotional moment, said Yee Leng Xiong, who translated for the two men. And Hmong leaders believe it was the first time a presidential candidate has ever met with a Hmong veteran as part of a campaign.

Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group of voters in the U.S., and in Wisconsin, Hmong are the largest Asian population. Both parties have reason to seek their votes.

So far, available data suggests Hmong Americans lean heavily toward Democrats. It’s the result of years of groundwork by the Democratic Party’s Asian American-Pacific Islander (AAPI) activists and representatives. And this year’s presidential campaign has included more extensive outreach to Hmong voters than any that’s come before.

Starting in 2018, Democratic members of the AAPI caucus reached out to Hmong elected leaders at all levels across Wisconsin to try to gather support for the eventual Democratic presidential nominee. This year, they’ve led Hmong-language phone-banking and other outreach efforts to rally support, especially among older voters.

While Hmong voters may favor Democrats, the community doesn’t vote as a bloc. There are conservative older voters, entrepreneurs sensitive to taxes and regulation, and enthusiastic supporters of President Donald Trump. A Trump campaign spokesperson said the campaign has maintained a presence at Hmong events throughout the state, and has been endorsed by the Rev. Candie Herr of Milwaukee and others.

But the work of attracting Hmong votes to Trump is made more difficult by the president’s attacks on refugees and his administration’s hardline policies on immigration and deportation, which has affected the Hmong community. On the Democratic side, some who’ve gotten involved in the 2020 campaign say it’s their first time getting involved in national politics.

“I have never put myself publicly or vocally out there in terms of politics,” said May Yer Thao, who co-chairs Wisconsin AAPIs for Biden. This year, “I could not say ‘no.’ We have too much at stake in this presidential election.”

Trump Rhetoric, Deportations Policy ‘Hits Close To Home’ For Many Hmong Americans

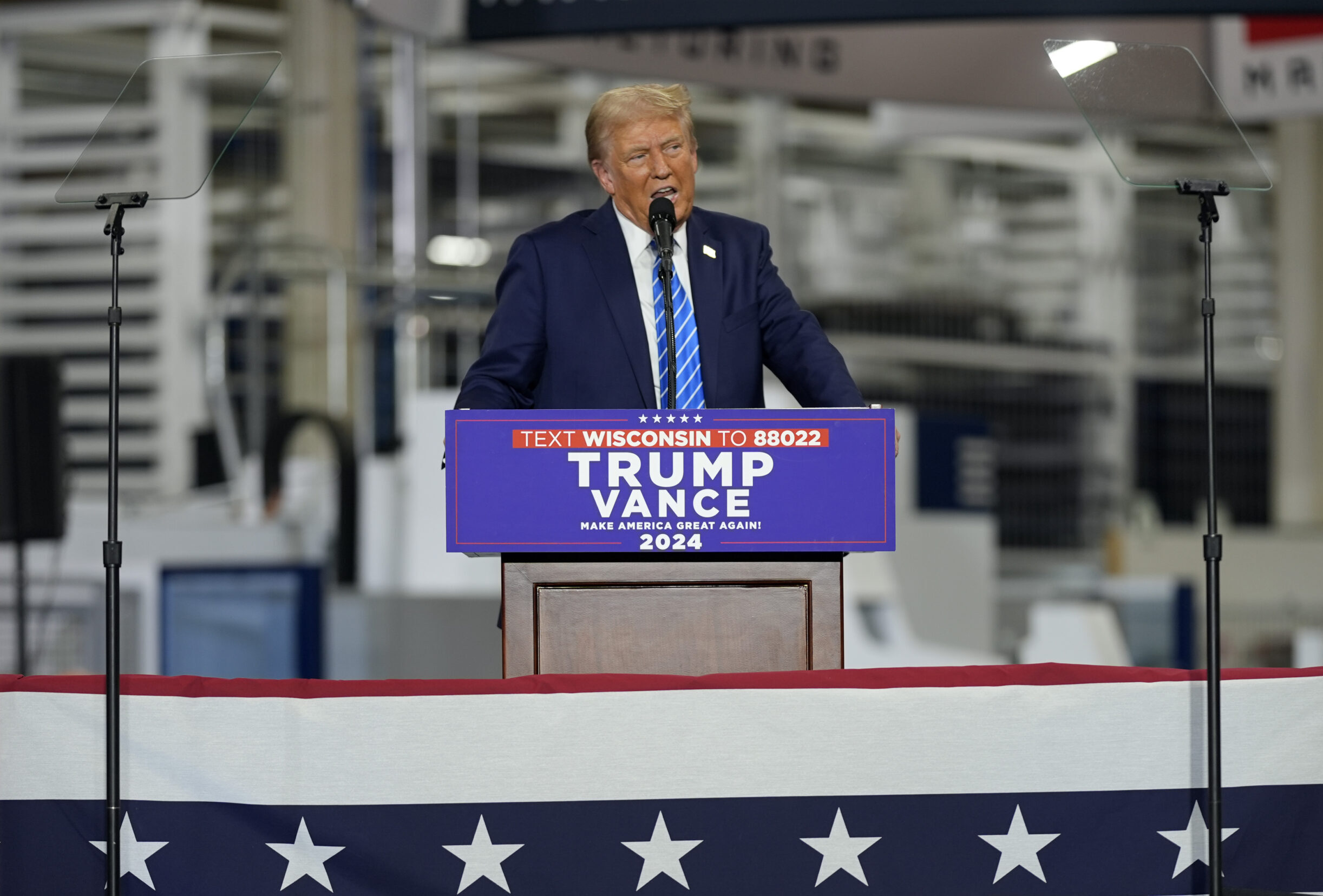

In a late September rally in Duluth, Minnesota, Trump warned darkly of “Joe Biden’s plan to inundate your state with a historic flood of refugees … coming from the most dangerous places in the world, including Yemen, Syria and your favorite country, Somalia.”

The sarcastic ad-lib inspired loud boos in the mostly white crowd.

“Right?” Trump said. “You love Somalia. This guy loves Somalia,” he said, pointing to a member of the jeering crowd.

Trump didn’t mention Hmong people. But plenty of Hmong people hear his anti-refugee rhetoric as extending to them.

“We were former refugees,” Thao said. “That includes us.”

In 2016, Trump’s signature campaign promise was to build a wall on the southern border to keep immigrants out. As president, Trump has pursued policies to reduce legal immigration, deny entry to refugees and increase deportations.

The majority of Hmong people living in the U.S. are citizens. But the communities are not far removed from their past as refugees, and for many, that past makes them sensitive to the effects of anti-refugee rhetoric. There are more direct effects, too. In February, news that the Trump administration was negotiating with the government of Laos for the ability to deport thousands of Hmong people who committed crimes years or decades ago galvanized leaders to speak out.

“In the Hmong community, we all know — this is not an exaggeration — we all know somebody who runs the risk of being deported,” Thao said. “It is that close to home for each and every one of us.”

A Trump campaign spokesperson did not address questions about whether the Trump administration’s efforts to allow deportations of Hmong residents to Laos would make it harder for them to win Hmong votes.

Ka Lo, a member of the Marathon County Board in Wausau, spoke about the Trump administration’s immigration policies at a Feb. 13, 2020 rally in the city. Rob Mentzer/WPR

Hmong people have also pointed to Trump’s use of anti-Asian slurs around COVID-19 as evidence of the damage his rhetoric can do. He repeatedly referred to the disease as the “China virus” or by the racist nickname “kung flu” even as xenophobic attacks on Asians increased across the country. In Stevens Point, police said a 57-year-old white man harassed Asian Americans in a grocery store in May — one of dozens of reported incidents of anti-Asian harassment or vandalism in Wisconsin.

“We can’t have a president that’s out here saying things like ‘the China virus,’” said Ka Lo, a member of the Wausau School Board and Marathon County Board. “We need a new president.”

In Wisconsin, Republican politicians have spent years developing relationships in the Hmong community, particularly in parts of the state such as Wausau that have a high concentration of Hmong people.

Former Gov. Scott Walker spoke at the inaugural Hmong Wausau Festival in 2017. Wausau-area state Sen. Jerry Petrowski, a former ginseng farmer, has worked closely with Hmong leaders. In January, he and fellow Republican state Sen. Roger Roth of Appleton introduced a bill that would make every May 14 Hmong-Lao Veterans Day in Wisconsin.

When Trump held a rally in Mosinee in September, a Hmong pastor, Yauo Yang, gave an invocation prayer at the event.

Yauo Yang, center, prays before a rally in Mosinee for President Donald Trump on Thursday, Sep. 17, 2020. Angela Major/WPR

The Trump base isn’t exclusively white. There is evidence in polling that Trump has gained ground with Black and Hispanic voters, particularly among men, and Hmong activists said a similar trend exists among Hmong men. In an interview with a Minnesota Hmong TV station this month, members of a Hmong veterans group endorsed the president. Former Republican congressional candidate Sia Lo heads Minnesota’s GOP Hmong outreach operation.

But Trump’s policies have clearly complicated that outreach. In February, before Lo lost the Republican primary in his congressional district, he told a Hmong TV station in the Twin Cities that if elected, he would “do everything in his power to stop the deportation of Hmong and Lao residents back to Laos” — that is, he would work to counter Trump administration efforts.

Not all the issues that motivate Hmong voters are specific to Hmong people.

On a Biden campaign virtual event featuring a dozen Hmong elected leaders from Wisconsin and Minnesota, health care protections and the COVID-19 pandemic were the major topics of conversation — the same topics that animate any other demographic group in the 2020 election. One of the speakers at the event, Jim Vue of the St. Paul School Board, was appointed to fill the seat that had been held by Marny Xiong, described by the New York Times as a “progressive dynamo.” Xiong died of COVID-19 in June.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.