On a recent summer day, about half a dozen teenagers gathered alongside their elders inside the Ho-Chunk Community Center in Black River Falls.

They met in western Wisconsin to record Hoocąk (pronounced “Ho-Chunk”) words and phrases for an upcoming app, designed to help people learn the language in the digital age.

“By the time we get done with this, we’ll be able to enter all of these sound recordings today into … the matrix, I guess, that we have set up for the app,” Ho-Chunk Language Division Program Manager Adrienne Thunder told the group. “Our hope is to have somewhere around 40 units of language, so people can work with that on their own or alongside a class that they’re taking.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Tribal leaders are working with the Language Conservancy, a nonprofit, to develop the app. They plan to have a beta version available this fall and release a publicly-facing version later this year.

There are nearly 8,000 enrolled members of the Ho-Chunk Nation, most of whom live in Wisconsin. But tribal leaders estimate there are fewer than 40 native Hoocąk speakers left in the entire country.

One of them is 83-year-old Maxine Kolner. For her, the loss of a language would spell the loss of something deeper.

“We can’t call ourselves a tribe because we lost our language and would probably be not considered Ho-Chunk anymore,” Kolner said.

Of the roughly 7,000 languages spoken worldwide, at least 2,900, including Hoocąk, are considered endangered

Based on current rates of language disappearance, the Language Conservancy estimates 90 percent of the languages spoken today could become extinct in the next century.

Those most in danger are Indigenous languages that were nearly wiped out after colonization.

“In North America, as well as Australia, we’re really at the epicenter of a worldwide extinction event when it comes to languages,” Language Conservancy CEO Wilhelm Meya said. “Language is the vehicle of so many things. … It’s essentially worldview. It’s where the history and where the stories where the songs and the prayers are expressed, and they’re expressed most authentically for that culture in that language.”

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Indigenous Americans were sent to boarding schools, where the federal government forced them to assimilate to white culture. Those effects are still being felt, Ho Chunk Public Relations Director Casey Brown said.

“All the Ho-Chunks that are alive today have a family member that went through being put in Indian schools where they weren’t supposed to speak their language,” Brown said. “They were supposed to forget their culture.”

The tribe has been working over the last several decades to revive the Hoocąk language. That includes an apprentice learning program, where aspiring instructors learn Hoocąk from elders known as eminent speakers. Today, there are Hoocąk instructors in at least five high schools across Wisconsin.

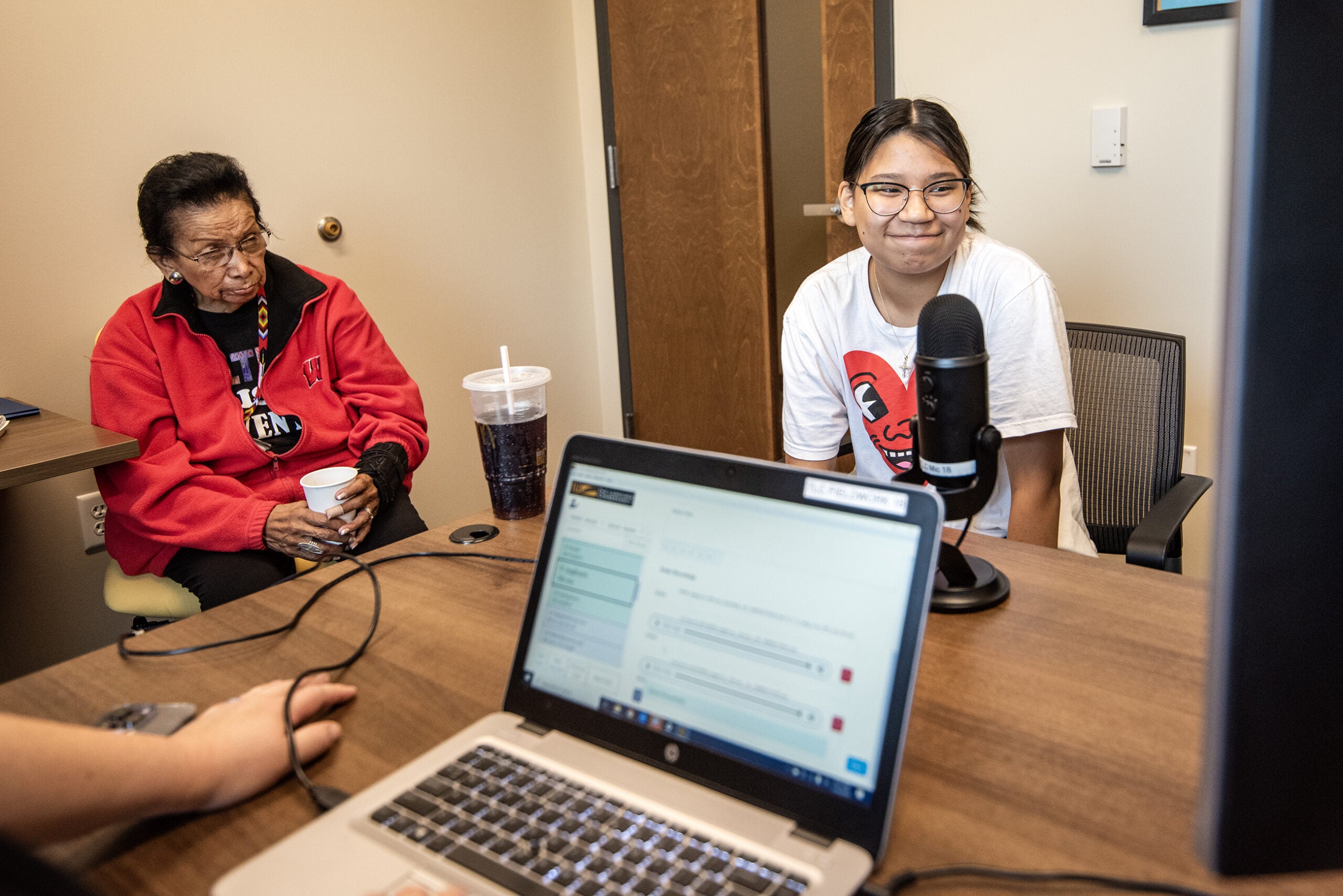

Last year, the Ho-Chunk Nation partnered with the Language Conservancy to launch an online dictionary with words recorded by elders. But for the forthcoming app, the Nation is using younger voices like that of Kaine Hall, an 18-year-old who took Hoocąk as a second language at Black River Falls High School.

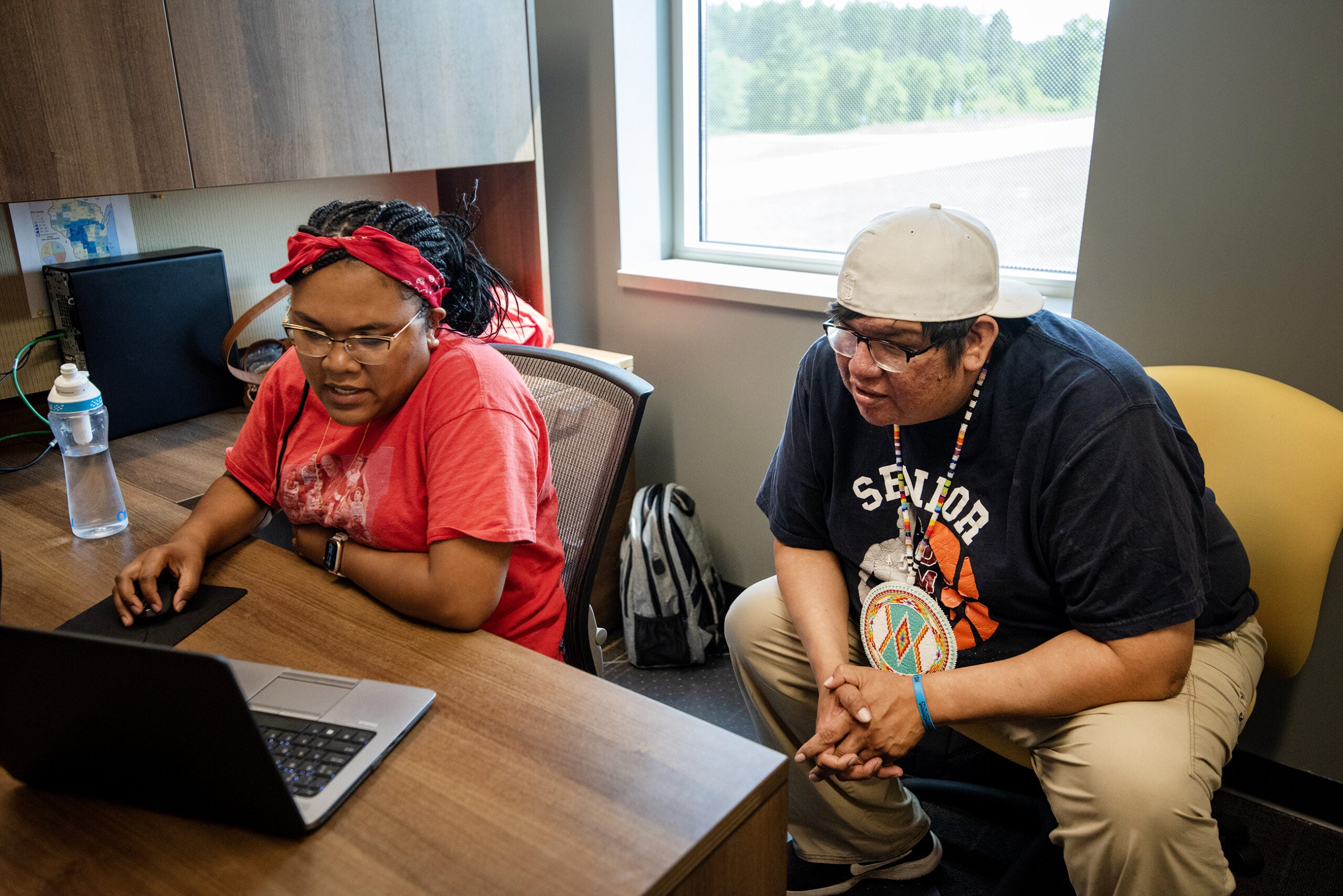

Inside the community center, Hall records phrases for the app like “He is a first son” and “Are you a first daughter?” Eighty-five-year-old eminent speaker Myrtle Long is on hand to correct his pronunciation.

The knowledge of elders like Long is essential, said the tribe’s Education Coordinator Jessi Falcon. Hoocąk used to be an exclusively oral language and native speakers understand nuances that can’t be conveyed in writing.

For English speakers, Hoocąk can be tricky, Falcon said. For instance, Hoocąk’s grammatical structure shifts based on whether the person being spoken about is sitting, standing up, lying down or moving.

“The language is so specific that you should be able to close your eyes and then when somebody is speaking you can picture it exactly the way that it’s happening,” she said.

Falcon sees the language as a link to culture. That’s part of why she sent her daughter, Naomi Littlegeorge, to a Hoocąk immersion day care.

But once Naomi went to school, she started speaking less Hoocąk.

“I had family members kind of saying, ‘Why aren’t you making her speak Hoocąk? We need her speaking Hoocąk,”‘ Falcon said.

Falcon felt it had to be her daughter’s choice.

“The state of the language is very important,” Falcon said. “But that’s a lot to put on those little bitty shoulders.”

Now, Naomi’s 16. She giggles when she shares her favorite Hoocąk phrase, which means he or she is bow-legged.

“The Hoocąk language is very specific like with who’s talking, who’s doing what,” Naomi said. “And who looks like what.”

Naomi’s affection for Hoocąk was apparent when she chose to spend part of her summer doing recordings for the new app. The goal: Bring Hoocąk to another generation of speakers.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.