Brian Decorah had something to share.

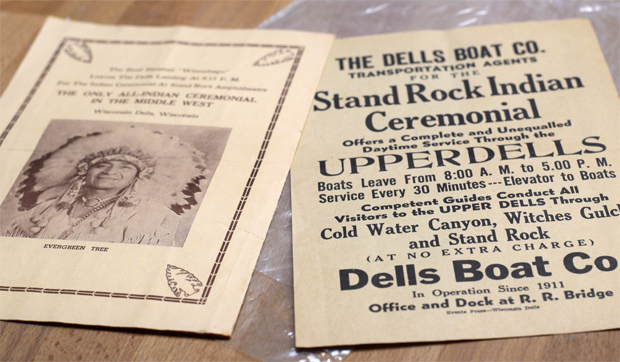

He walked into the Ho-Chunk Museum and Cultural Center on Monday and handed a program from 1942 of a Native American ceremony in the Wisconsin Dells to museum director Josie Lee.

“I’d like to donate this,” Decorah said, pulling the two brochures out of a plastic sleeve. Decorah had a tie to the program: his parents used to dance in the ceremony that called together people across the state and beyond to an amphitheater at Stand Rock to celebrate the culture and history of the Ho-Chunk, which at the time was called the Winnebago Indians of Wisconsin.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Decorah’s donation is one of 200 items and countless photos and archives curated by the newly established and long-awaited museum, which opened Friday in downtown Tomah, 1108 Superior Ave. The building, previously occupied by the Tomah Journal, is marked by a turquoise door and window decals. It has wood floors, exposed brick and a full kitchen in the back.

The museum’s growing archives are stored at the museum, and will be part of exhibits that will rotate out every three to four months. Lee said she is already planning exhibits on basketry, Ho-Chunk warriors and Ho-Chunk fashion.

“I want to tell the Ho-Chunk story in all of our facets,” she said.

The museum has a shared responsibility for creating a safe space for Ho-Chunk members and for giving Ho-Chunk youth a lens into where they came from.

That was once something tribe members depended on their parents and elders to teach them, said Ho-Chunk member Eliza Green, who worked for the Ho-Chunk Department of Cultural Heritage and shared an office space with Lee when she was searching for an office.

“Our children need to know where they come from and know that this is always going to be their territory, this is always going to be their life,” she said. “They’re always going to have a place to call home and that’s what everybody should have.”

The museum opens with the Clarence Boyd Monegar Exhibit, which features a collection of paintings by Ho-Chunk watercolor painter Monegar, whose landscape art captured the natural elements of Wittenberg, about 30 miles east of Wausau, where he was born and attended the Indian Parochial School.

Lee felt positive about Monegar’s artwork kicking off the opening of the museum, particularly because it doesn’t subjugate Native Americans by reinforcing stereotypes. Not all Native Americans wear beads and feathers, she said. And comparing women to earth and earth tones is a “colonialistic mindset” that likens women to property that can be dominated and controlled.

“One of the reasons I was so happy to go with this artwork in the beginning is because I didn’t want to continuously portray stereotypical imagery,” she said.

Lee also displayed framed photographs of items that have cultural and historical significance for the Ho-Chunk. The photos were items from Lee’s own collection and were taken by seventh- and eighth-grade students.

Lee hopes to be able to offer more regular educational classes as the museum grows, for example on beadwork and basketry.

The Ho-Chunk Nation is widely recognized as one of Wisconsin’s first Indigenous tribes, originally occupying territory from the Green Bay area west into Minnesota, south through Iowa and back north along the Rock River. Federal government treaties pushed the Ho-Chunk farther west and south, effectively shrinking the area occupied in Wisconsin.

The first written recordings of the tribe date to the 1630s, when the French made contact.

Now, members of the Ho-Chunk nation are spread out in 26 counties in three states comprised of 13 main communities. Most of Wisconsin’s population is congregated in the Black River Falls, Wisconsin Dells and Tomah areas, and in the Wittenberg area, Lee said. The Winnebago of Nebraska also are Ho-Chunk, Lee said. That tribe is descended from Ho-Chunk who were sent there as part of the state’s effort to push out Native Americans.

“One of the reasons we picked Tomah is it’s the most centralized, at least for this point in time,” Lee said of deciding where to establish the museum. “Everyone can get here within equal travel distance.”

Wisconsin is home to 11 Indigenous tribes recognized by the federal and state government. Some of them have established museum and cultural centers, including the Oneida Museum, the Menominee Indian Tribe Cultural Museum, the Lac du Flambeau Chippewa Museum and Culture Center. Exhibits are also on display at numerous public museums and historical societies.

Opening a museum and cultural center showcasing the legacy of the Ho-Chunk Nation had long been a dream of many of its members and hit numerous road blocks as priorities within the tribe changed and evolved.

“We have so many tribal members and there’s so many priorities,” Lee said. “It makes sense to me that it took so long, because we had to make sure we were taking care of the people first.”

Attempts were made in the 1960s to establish one, but they failed. Nearly 50 years later, Lee served on a committee that was formed in 2010 to try again, but that fizzled out when it’s organizing member, Anna Rae Funmaker, got sick and died.

Lee was a natural fit to lead the museum, in part because of her education, which included a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which she earned in 2010, and a master’s degree in museology in 2013 from the University of Washington.

She returned to Tomah at the request of her uncle to help set up the museum in 2013. But the museum was still a dream, without a location and with funding stalled in the Ho-Chunk Legislature. After arriving back home, Lee spent the next one and a half years working as a bilingual education manager, writing curriculum in Ho-Chunk for schools. In her off hours, she wrote a job description for a museum director and pitched it to members of the Ho-Chunk government.

She competed against other applicants for the job. Two weeks before she was due with her daughter, Penelope, she got the job.

But it would still be three years before she would get the keys to the building. Much of that time was spent planning and searching for a location for the museum, which Lee serendipitously found while attending a fundraiser at the museum’s current location.

Delays with the project continued in part because of turnover with the government and funding delays. Funds that were caught up in government processes were eventually released, allowing Lee to purchase the building in 2018.

Friday’s opening came months after a planned opening last July. This time, the delay was because of necessary renovations, some of which were paid for through an anonymous donor.

As the museum’s only employee, Lee already has big dreams for a 50,000-square-foot exhibit space and a staff of 20, she said with an electric laugh. That’s not so hard to imagine for the woman who helped establish a tribal museum in five years. The national average is 20, she said.

“Apparently, I’m very goal driven,” she said with a smile.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.