Paul Bunyan stories are plentiful.

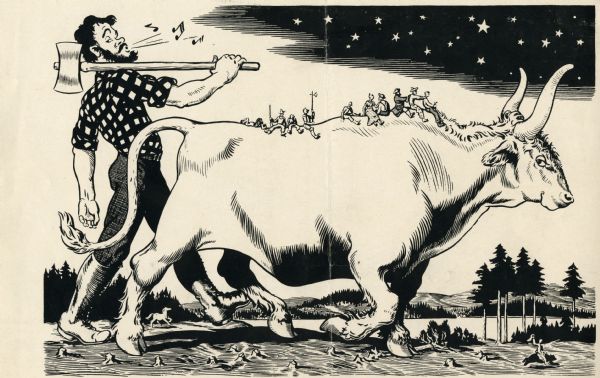

He cleared forests with one swing of his ax. He and his trusty bovine, Babe the Blue Ox, dug the Great Lakes to quench the thirst of his fellow loggers. He created the Mississippi River by simply dragging his ax behind him.

He’s a Wisconsin folk hero.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But why? That’s what Ryan Urban of Rice Lake wanted to know, so he reached out to Wisconsin Public Radio’s WHYsconsin.

“It’s hard to travel around northern Wisconsin or Minnesota — Michigan for that matter — without seeing something Paul Bunyan related,” Urban said. “I guess I started to ask myself why … I wanted to know, OK. How did this start? Was Paul Bunyan a real person? Was it based on a real person? And how did the legend form?”

To get some answers, WHYsconsin reached out to Michael Edmonds, a historian who wrote the preeminent book on Paul Bunyan, “Out of the Northwoods.”

Here’s what he had to say about the flannel-wearing Northwoods folk hero.

“Paul Bunyan was for decades, in the last century, the best-known American folk hero. He was Thor. He was Ulysses. He was America’s greatest folk hero,” Edmonds said.

Paul Bunyan stories are also complicated. They come from a tradition of fantasizing white expansion and promoting deforestation. In 2019, a Paul Bunyan statue in downtown Bemidji, Minnesota was spray-painted with the word “genocide.” For some, Paul Bunyan’s presence across the upper Midwest only amplifies the forced relocation of Indigenous people that called this area home.

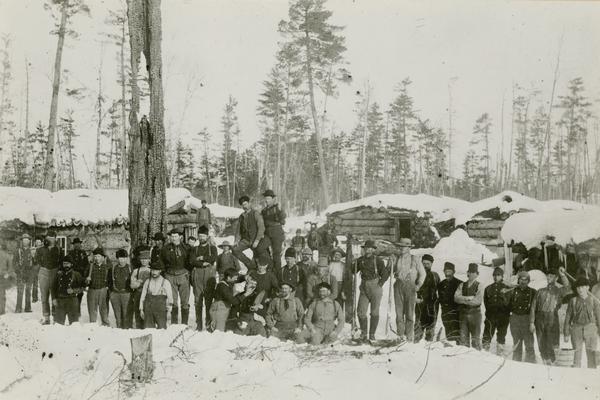

Records of oral traditions date Paul Bunyan stories back to the 1880s. The first noted reference to the larger-than-life logger comes from a timber camp near Tomahawk during the winter of 1885-86.

There’s no good evidence that his character existed or was based on anyone real. Edmonds said Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox were just part of stories told as a way for loggers to pass the time — and prank the younger workers.

“One of the ways they outdid each other was for — in logging camps — aging veterans who were in their 40s and 50s, trying to put one over on the young teenage guys who were there by saying they worked for Paul Bunyan,” Edmonds said before launching into one of the common early Paul Bunyan stories. “‘It was so cold, you know, the words froze the air and fell to the ground and broke into pieces.’”

The tales were also a way for loggers to commiserate over how dangerous the job was.

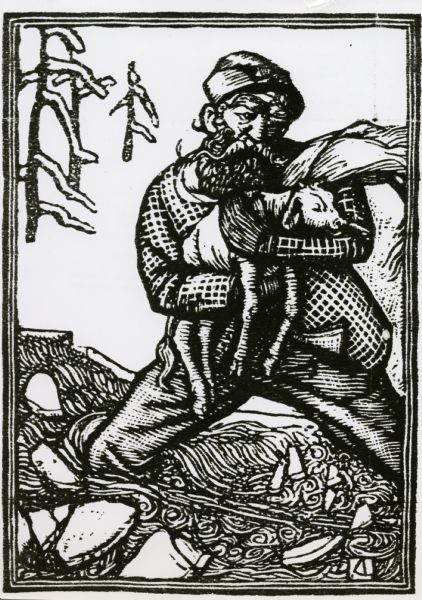

“The early stories are full of people who’ve lost a limb or lost a finger or whatever, and Bunyan is often coming to their rescue. He’s their superhero,” Edmonds said.

In the 1930s, another Wisconsin hoaxster named Eugene Shepherd claimed to have created Paul Bunyan.

Shepherd was a lumberjack and humorist — famous for coming up with the hodag, a mythical beast with green fur, red eyes and giant claws. Shepherd claimed the hodag was real and charged people to see it. The hoax made Oneida County a tourist destination, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

“He had been a timber cruiser and a lumberjack … and he was — during that winter of 1885-86 — in the Tomahawk area, not far away in the woods with a crew,” Edmonds said. “So it’s possible that he was telling the truth when he claimed to have invented Paul Bunyan.”

But Edmonds said Shepherd “lied outrageously” and was known for plagiarizing other people’s work, pointing to Kurt Kortenhof’s book “Long Live the Hodag: The Life and Legacy of Eugene Simeon Shepard, 1854‐1923.”

“Anything that (Shepherd) said has to be taken with a grain of salt,” Edmonds said.

Regardless of who is responsible for Paul Bunyan’s existence, Edmonds said all evidence points to the Tomahawk logging camps as the place of origin.

Out of the woods and onto bookshelves

The first time Paul Bunyan made it into print was Aug. 4, 1904, in the Duluth Evening News. His stories reached a larger audience after running in a Milwaukee-based nature magazine named “The Outer’s Book” in February 1910, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Fast forward to 1915, when the Red River Lumber Co. in Minneapolis began an advertising campaign capitalizing on Paul Bunyan’s popularity. The company shared the lumberjack’s stories in a catalog that was mailed to lumber yards across the United States.

“And so Bunyan escaped the woods, into the lumber industry as a whole,” Edmonds said.

And the key to Bunyan’s success was that Red River Lumber didn’t copyright the stories — making the more than 100,000 copies they published were fair game. Publishers and newspapers took advantage of the free cache of stories around the 1920s and found tremendous success.

Edmonds referenced two collections of Paul Bunyan stories from the mid-1920s that share first-hand stories from logging camps in Northern Wisconsin — one by Esther Shephard and one by James Stevens.

“To put them in context, between 1925 and 1940, those two books sold 600,000 copies,” Edmonds said. “‘The Great Gatsby,’ which also appeared in 1925, sold 20,000 copies.”

As Paul Bunyan’s stories began to appear in print, the tales changed. Some of the fire-side ramblings told by veteran lumberjacks to fool their young comrades were unfit to print due to censorship laws. So the stories were toned down, catering instead to a more buttoned-up middle class.

Today, Paul Bunyan tales are reserved for children’s books, roadside attractions and college football rivalries.

Other states attempt to lay claim to Paul Bunyan

Wisconsin isn’t the only state that claims to be the birthplace of Paul Bunyan. Bemidji, Minnesota says it’s the birthplace of Paul Bunyan and his trusty ox Babe.

But Edmonds said those other states are just plain wrong.

“The only evidence that I could find places his birth — so to speak — not in Minnesota, but in north-central Wisconsin,” he said.

Editors and publishers from Maine, Pennsylvania and even Canada tried to adopt the folk hero as their own, Edmonds added.

“In my book, I investigated all of those claims, and there’s nothing behind them,” he said. “They’re just either mistaken or propagandist memories of other states.”

No matter what forests Paul Bunyan hails from, the lumberjack’s staying power remains strong. It’s something that’s puzzled both Urban and Edmonds.

“It just seems so quaint and old-fashioned, yet the legend lives on even now,” Urban said.

Edmonds agreed.

“It’s easy to understand how during the ’30s, and ’40s, even into the ’50s — you know, this was nostalgia. This was an idealized mythical frontier, like the one they recalled from their childhoods. So, you know, from 1915 to 1960 maybe, it’s really easy to understand why the stories were popular,” Edmonds said. “After that? I don’t know. I don’t get it.”

Reasoning aside, it seems Paul Bunyan is here to stay, along with the rivers, lakes and hills he’s said to have created.

This story was inspired by a question shared with WHYsconsin. Submit your question below or at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it.