Fruit flies and humans may have more in common than you think.

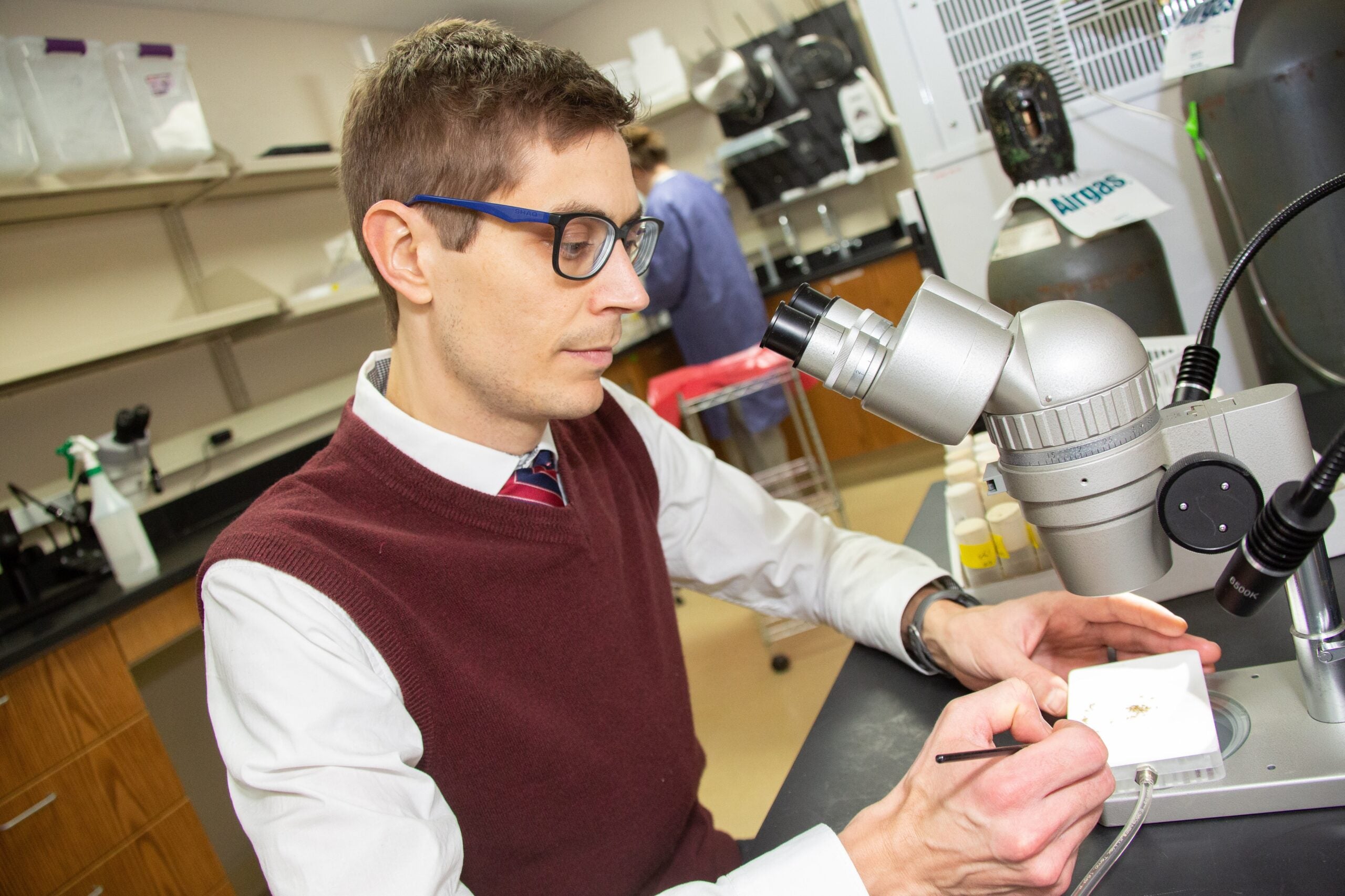

Flies were used during early research into human genetics, said Dr. Doug Brusich. Brusich, an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, is among a group of researchers who now use the insect to study traumatic brain injuries. Their findings could have implications for athletes.

Brusich co-authored a paper published last year in the journal Fly focusing on the effects of repetitive, mild brain injuries — the same type that might be suffered by offensive or defensive linemen. The researchers found mild brain injuries in quick succession have a compounding affect, which they referred to as synergistic, and can cause the same level of impairment as a single more severe injury.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Brusich has been working with flies for 10 years. Flies have all the same types of genes humans do, he said. Whereas humans often have multiple versions of each gene, however, flies can have just one.

“So if you were to make a mutation in the one version of the fly gene, you might get a nice model for disease that’s a simpler way to study it than it would be in the human system,” Brusich said.

With the help of several undergraduate researchers, Brusich anesthetizes flies in his lab and sorts them into individual vials. They then use a spring mechanism to launch the vials, at varying angles, against a padded surface. The method was developed by University of Wisconsin-Madison geneticists Dr. David Wassarman and Dr. Barry Ganetzky, Brusich said. It causes the flies to experience the same acceleration, deceleration or rotational forces a human might go through in a car crash.

Research on flies can yield quick results, Brusich said. It’s also easy to isolate a control group when studying brain injuries in flies. The same can’t be said for humans.

In her field, concussion treatment is becoming more personalized, said Sadie Buboltz-Dubs, clinical coordinator for UW-Green Bay’s new Master of Athletic Training program. Different factors like genetics and lifestyle can play a role in a person’s outcome after a concussion.

“We want to help our patients as much as we can, and we can help them better if we have a better understanding of what’s happening,” she said.

Researchers can also study conditions in flies that are challenging to study in humans. Flies have been used to research chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). The diagnosis of CTE, which was linked to professional football players in 2002, can only be confirmed in patients when they’re dead, Brusich said.

According to the CTE Center at Boston University, a person’s risk of developing the neurodegenerative disease doubles for every 2.6 years they play football.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.