Cavendish might look like any other small Vermont town. Nestled between rolling hills and the Black River, with one main street running through town, it’s a launching point for trout anglers, snowmobilers and skiers. But this rural town of just over a thousand people can claim a remarkable historical figure: Phineas Gage.

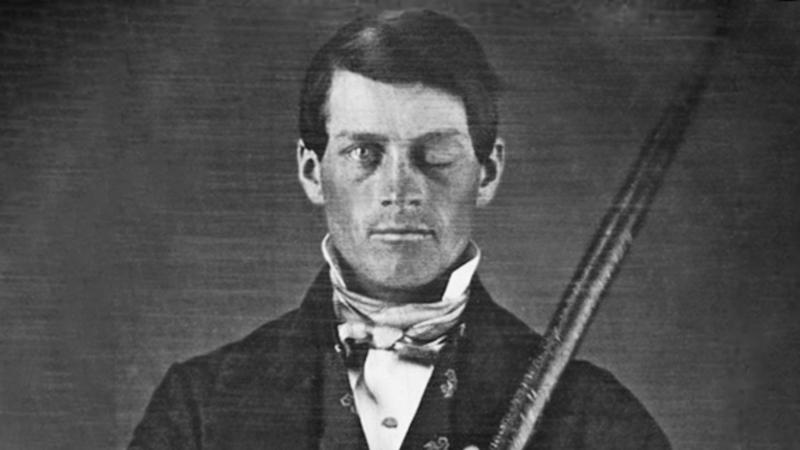

Gage was a young construction foreman who suffered a gruesome accident that changed the history of brain science.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

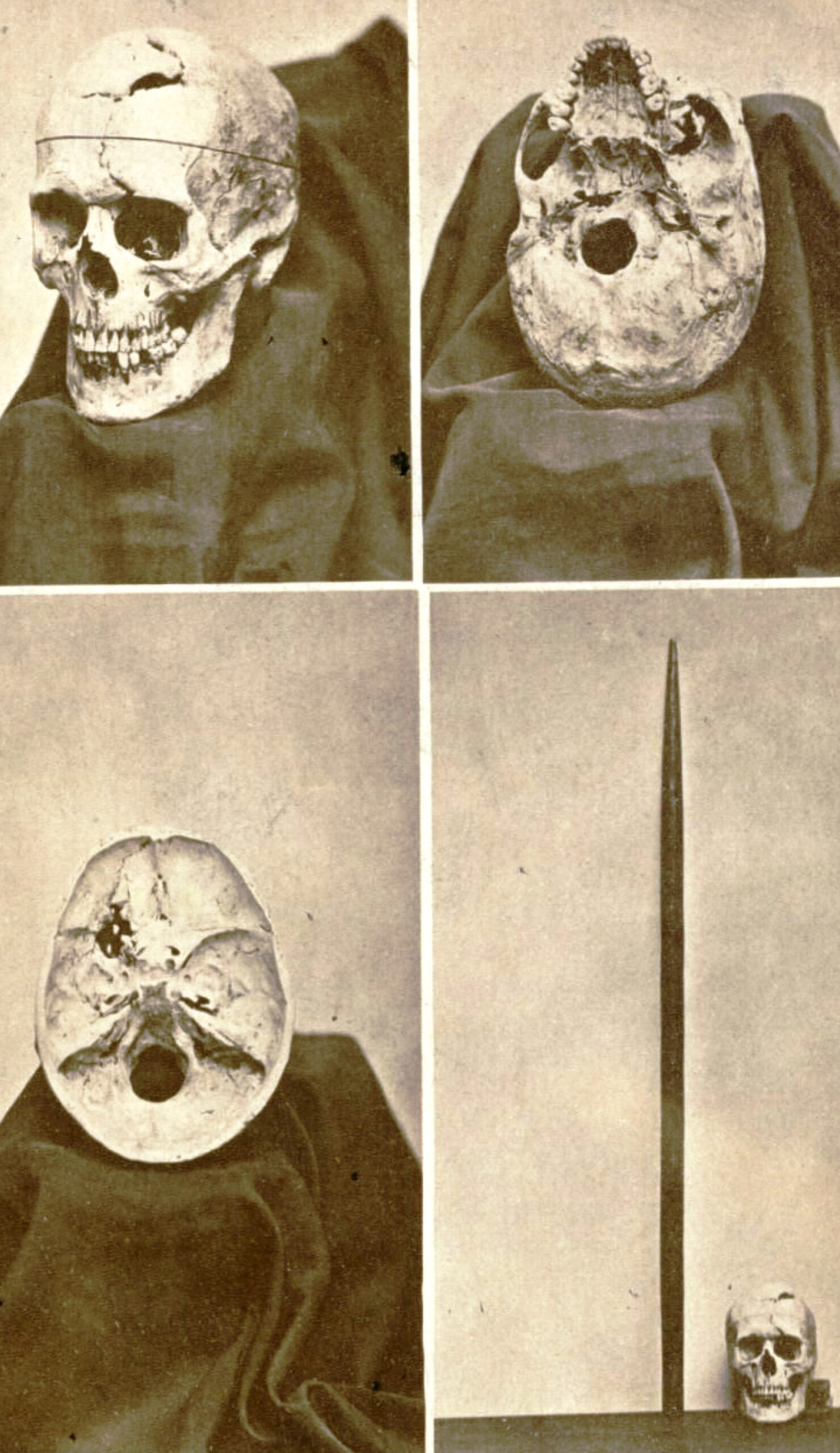

In 1848, while blasting through rock to build the new railroad, an explosion sent a 3-foot, 13-pound iron rod up through his cheekbone and out the top of his skull. The tamping rod landed 80 feet away, “smeared with blood and brain.”

Remarkably, Gage lived for another 11 years. He lost one eye and had a permanent hole in his skull, covered by a thin layer of skin.

Gage was a medical marvel.

There had been a long-running debate in the 19th century on whether different regions in the brain govern different behaviors. Here was a case of severe damage to the left frontal lobe, followed by a dramatic personality shift. It seemed to prove the point once and for all.

“It laid the path for the first real brain surgery in 1885,” said Margo Caulfield, director of the Cavendish Historical Society, told “To the Best of Our Knowledge.” “It opened up a whole new horizon. You can survive a brain injury, you can touch the brain, which means you can do surgery. It’s really, really huge.”

Gage himself was never the same after the accident.

He’d been well-liked by his co-workers and his employer, but later, his doctor reported that he became “fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity.”

A friend said, “Gage is no longer Gage.”

[[{“fid”:”1360831″,”view_mode”:”embed_portrait”,”fields”:{“alt”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”,”title”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-landscape media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″,”format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3E%3Cspan%20style%3D%22font-family%3Aarial%3B%22%3ESteve%20Paulson%20of%20%22To%20the%20Best%20of%20Our%20Knowledge%22%20in%20Cavendish%2C%20Vermont%2C%20near%20a%20marker%20remembering%20Phineas%20Gage.%20%3Cem%3EAnne%20Strainchamps%2FTTBOOK%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fspan%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“2”:{“alt”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”,”title”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-landscape media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″,”format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3E%3Cspan%20style%3D%22font-family%3Aarial%3B%22%3ESteve%20Paulson%20of%20%22To%20the%20Best%20of%20Our%20Knowledge%22%20in%20Cavendish%2C%20Vermont%2C%20near%20a%20marker%20remembering%20Phineas%20Gage.%20%3Cem%3EAnne%20Strainchamps%2FTTBOOK%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fspan%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”,”title”:”Steve Paulson in Cavendish, Vermont, near a marker remembering Phineas Gage.”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″}}]]”Based on my experience with people who’ve had similar types of injury, you can talk to them, and they sound completely cogent. And then you talk to them another time and it’s like, what planet are they on?” Caulfield said. “This is the horror of traumatic brain injury. Some families just cannot handle a patient like that.”

Gage was unable to work on the railroad, but he still needed a job.

For a while, he made money by exhibiting himself around New England as a curiosity, showing off the holes in his head and his famous tamping iron.

Then, he was offered a job as a long-distance stagecoach driver on the Val Paraiso-Santiago route in Chile. It was a 100-mile route, and 13 hours of handling a coach and six horses, plus passengers, over rough terrain.

Gage lived in Chile for seven years and then started having epileptic seizures.

He died in 1860 at the age of 36.

Over the years, scientists have interpreted Gage’s story in different ways.

At first, he was seen as a triumph of human survival. Then for decades he became a textbook case for post-traumatic personality change. More recently, Gage’s case has been interpreted as a story of resilience. For a man who was supposedly anti-social and volatile, Gage’s ability to hold onto a challenging job in Chile suggests he’d regained his independence and social adaptability.

Perhaps Gage’s story is a textbook case of another sort, showing the brain’s capacity for rewiring after trauma. This gift of neuroplasticity is why we’re able to handle so much that life throws at us.

“I am fascinated by what he overcame to survive for as long as he did,” Caulfield said. “The resiliency piece of his story fascinates me … I think resiliency is just hard-wired into our DNA.”