Hannah Beauchamp-Pope was wearing new Nike sneakers when she led a march through the streets of downtown Green Bay almost a year ago in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

It was organized by a local nonprofit called We All Rise, and the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay student wasn’t expecting to take the helm, but seeing all the people behind her was energizing, she said.

“Just the fact that we all moved as one community, it gives you goosebumps,” the 19-year-old said. “And to be at the front of that, and kind of leading that, it just put into perspective what you can do when you believe in yourself.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Her friend Yakaukwetákate Gaia, 20, was at the march too. She was surprised to see people from so many ages and backgrounds, she said. At one point, protestors laid down on the Main Street Bridge for 8 minutes and 46 seconds — the same length of time former police officer Derek Chauvin was believed to have knelt on Floyd’s neck.

“You could feel the anger and the frustration, and the way that it just went silent, it was definitely kind of horrifying in a way, when you think about how that’s what that man experienced. Utter chaos and noise and fear and then nothing,” she said.

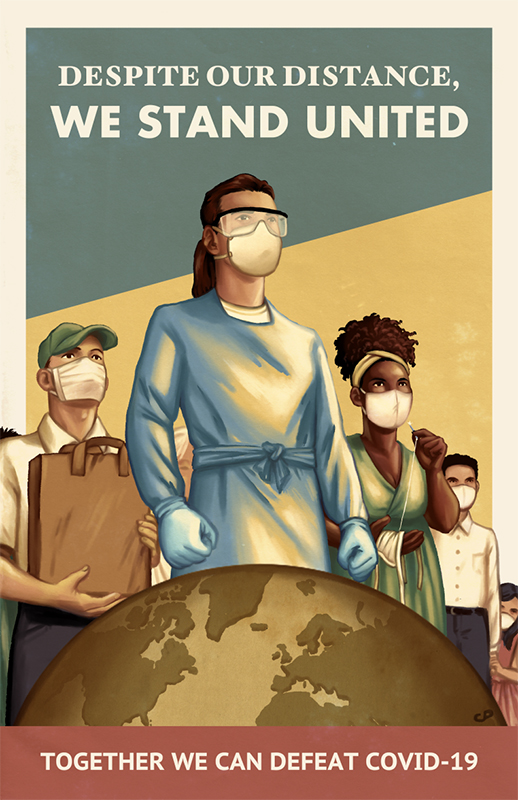

Last summer’s protests, set against the backdrop of a pandemic, were historic. And while activists were aiming to make the world a better place, and scientists and health care professionals were fighting to save lives, curators and historians were working to preserve our memories from a year we’ll never forget.

Documenting Stories Of Social Justice In Green Bay

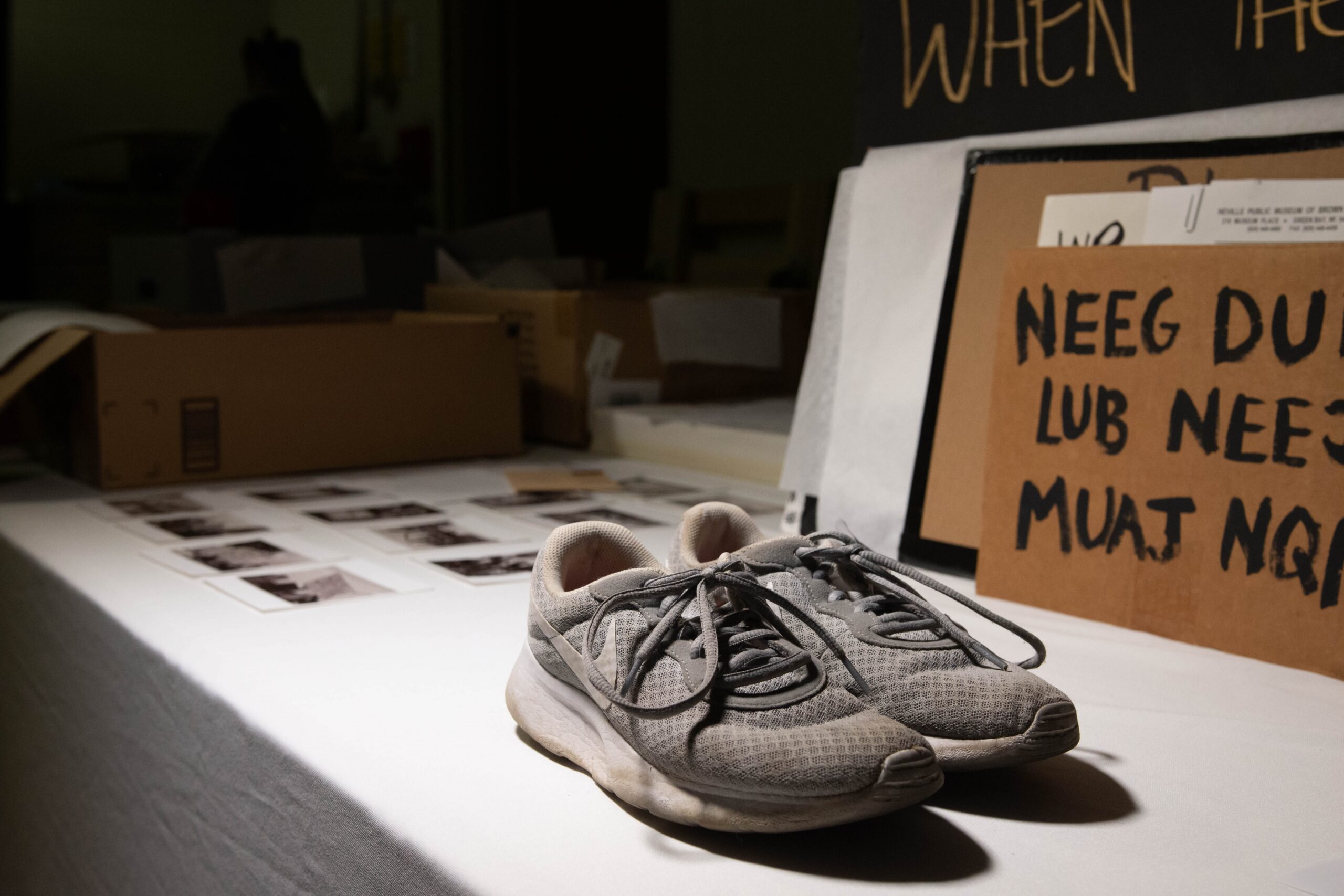

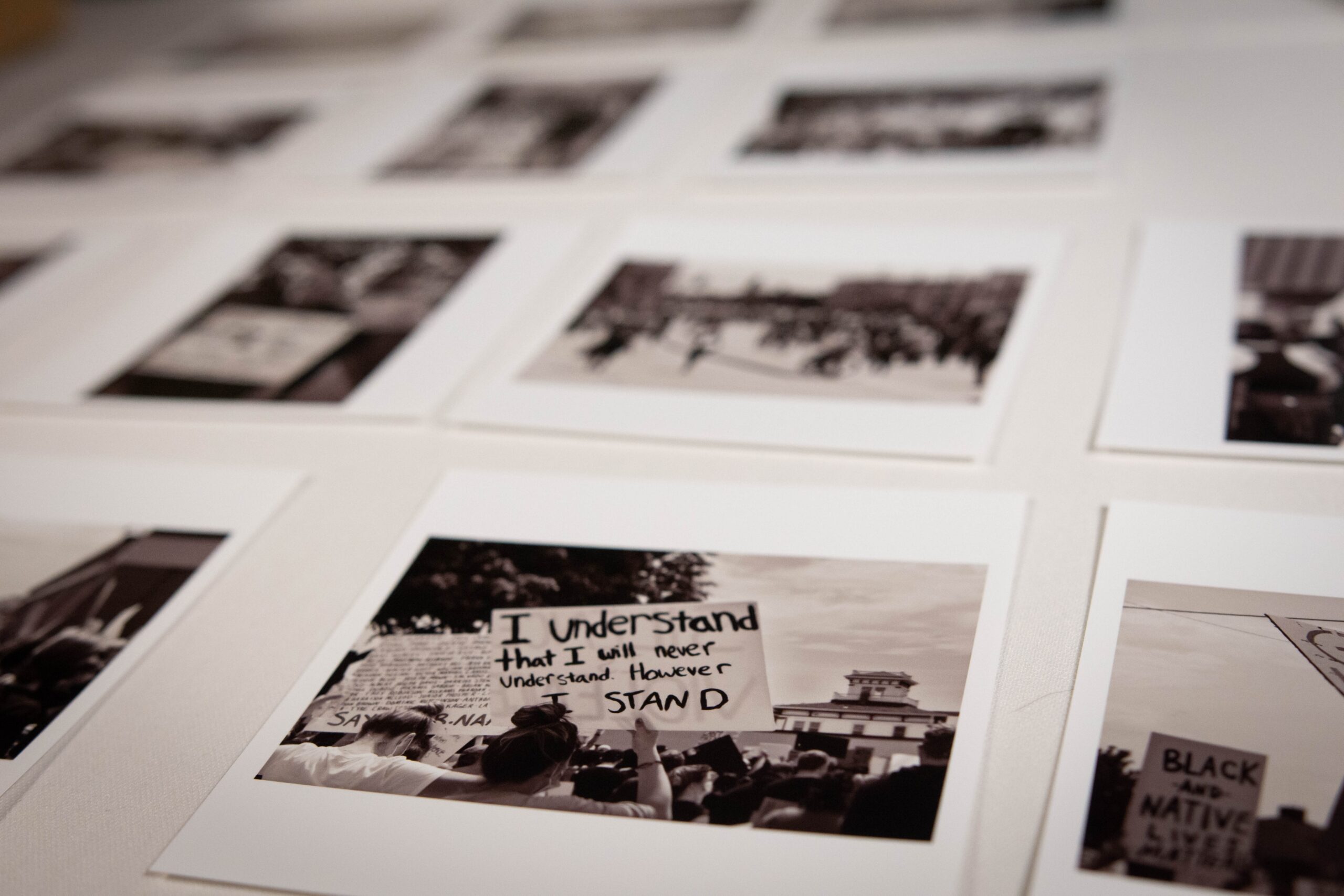

The march Beauchamp-Pope led in downtown Green Bay began near the Neville Public Museum. In hopes to preserve the moment, the museum put out a call for items related to the social justice movement. Beauchamp-Pope’s gray shoes are now part of its collection, which includes about 30 artifacts from last summer’s demonstrations.

“What we were trying to do was capture that moment in time and not have to chase down those artifacts 15 or 20 years from now,” said executive director Beth Lemke.

Last month, those items were being processed in the museum’s cavernous upstairs storage area. There was a megaphone, masks and photos. Lemke told Beauchamp-Pope not to wash the t-shirt she wore during the protest.

“We want it in the shape you actually wore it,” Lemke explained.

The museum kept a selection of posters, including one that says “Black Lives Matter” in Hmong.

“We talk all the time about inclusive collecting and making sure that our collection represents the people who live in Green Bay today, so this is just one example,” said curator Lisa Kain.

Almost a year later, Chauvin was convicted of murder. It’s a small step forward, but there’s still miles to go, Beauchamp-Pope said. Her activism isn’t over, but there’s still value in having it preserved for future museum-goers, she said.

“When we have those BIPOC students, those little Black girls and those little Native American girls, who come to our museum, they can see that the power of change and the power of transformation in our society is right in their shoes,” she said.

Preserving History During A Pandemic

The Neville is offered new items on a weekly basis, Lemke said. It’s at capacity for some things, like wedding dresses and military dress uniforms. It has more than 4 million feet of film and maybe a million physical items, the earliest dating back to Ancient Egypt, she said. But its current show, Spectacular Science, features a much more contemporary item — a cardboard box that held COVID-19 vaccines from Moderna.

Of course, the pandemic upended daily life for pretty much everyone last year, including museum curators. It presented a unique challenge, said Estella Chung, chief curator at the Wisconsin Historical Society, because it’s rare for historians to document events with so much emotional significance, she said.

“In a different year, there may be a very big issue, but it’s not particularly personal, nor do you necessarily feel fearful of catching an illness,” she said.

It’s also unusual to live through two watershed moments at once, she pointed out.

“So the challenge for our curators that collect artifacts is really to think very carefully about what to collect and to pay attention to all the different stories and voices and perspectives all happening at once,” she said.

Her team had to figure out the core stories it wanted to tell, with future historians in mind. It was a challenging brief when so much was uncertain early in the pandemic, including whether it was even OK to touch things. The Historical Society also didn’t want to disrupt history as it was happening, Chung said.

Among other things, curators have added makeshift masks, as well as ones that were first off the production line from Wisconsin manufacturers, to a growing pandemic collection.

While challenging, living through history also has its advantages, Chung pointed out.

“One of the wonderful aspects about collecting in the moment is, as a curator, you can write at length about the context because you’re living it,” she said.

Remembering Everyday Life During The Coronavirus

“Collecting history as it happens is a tradition in the Society,” Chung said.

And by early March 2020, the Historical Society was considering ways to document the pandemic, said director Christian Overland.

“We even started looking in our collections and thinking about what happened in 1918 and could we actually help the state by using history to look back,” he said. “Through that process, we realized that in our 1918 pandemic archive, the voice of the everyday life was missing.”

There are likely a few reasons the 1918 flu pandemic doesn’t feature heavily in our history classes, including the quickly evolving science that followed. Antibiotics were discovered in 1928, and the electron microscope was invented in 1931, Overland pointed out.

Still, the Society didn’t want to neglect everyday voices this time around, so they launched a COVID-19 journal project April 2.

Thousands of people have contacted the organization to say they’ll be submitting journals, and scores have already been turned in. One is coming from a former exchange student who’s back home in Italy, another is from a 14-year-old, who Overland said is the youngest contributor.

“There’s one great journal that came out of the Eau Claire region that people just put every receipt that they had had in it for like nine months, kind of what they bought and what they ate,” he said.

There are art and video journals. Some are somber, discussing traditions they had to forgo during the pandemic or even the challenge of grieving a loved one during social distancing, Overland said. Some talked about George Floyd’s murder. They cover weather, politics, COVID-19 case numbers and more, he said.

“Most people know that their writing will be read by somebody in the future. We get a kind of inkling of that,” Overland said. “They know that they’re laying down history, their own personal history and the history of their community.”

And it’s not the first time the Society has used journals to document the past. It has one from the Lewis and Clark Expedition, written by Charles Floyd, who died on the journey. It has some from the original Peace Corps volunteers and even more from the Civil War.

Today’s journals will help future generations, Overland said.

“Some people think that we just focus on the way past, but we’re always contemporary collecting … and thinking about the stories that are connecting the past to today and how they can help us build a better future,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.