Around 1994, John Armbruster was keeping to himself during a teacher’s in-service day when he overheard two fellow teachers talk about a soldier who fell 4 miles without a parachute and lived.

That couldn’t be right, he thought. But it piqued his interest, so he leaned forward. He heard a name, and it clicked that this man’s daughter, Joni Moran-Peterson, was a fellow teacher in the North Crawford School District. So, he found her that afternoon and asked: Could it be?

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Oh yeah. ‘Lean Gene the fighting machine,’” Armbruster remembered her saying.

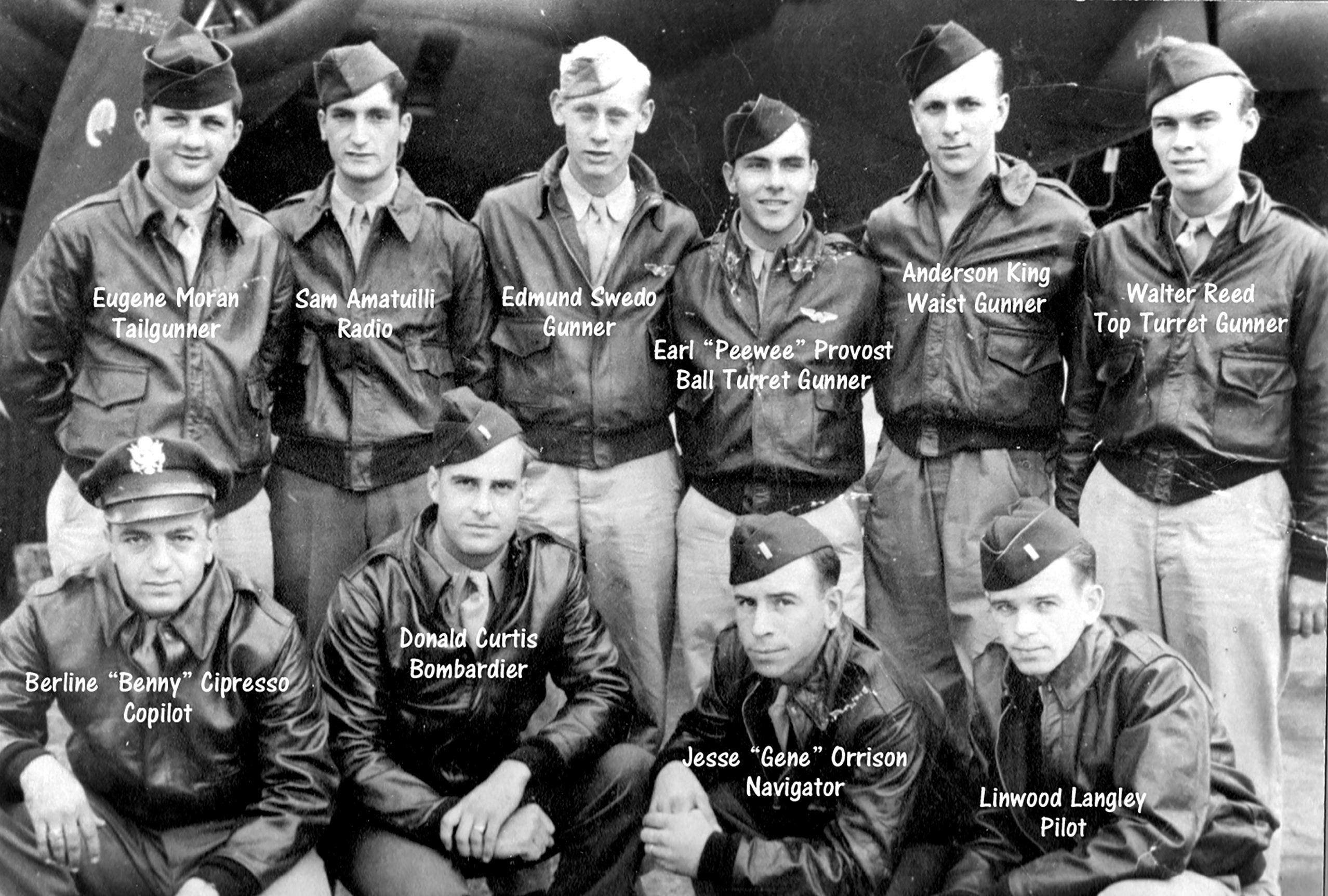

Armbruster’s mind started racing. The rookie history teacher started to hear layer after layer of this story — Gene Moran, the Soldiers Grove native whose Flying Fortress bomber was shot down in World War II, yet he somehow survived the 4-mile descent, the 17 months inside Nazi prisoner-of-war camps and a 600-mile forced march.

Armbruster had to share Moran’s story. There would be lessons and projects. Moran could come in and talk to a class. But Moran’s daughter told him that wasn’t an option. She told him: “We don’t go there.”

As was the case for so many families of veterans, the details of their loved one’s deployments remained largely unknown, untouched, undiscussed. But after years of Armbruster and Moran’s families becoming close and building trust, Moran agreed to share his remarkable story — but only if Armbruster wrote it.

After three years of interviews and research, Armbruster wrote the book, “Tailspin,” which came out April 30. Armbruster joined WPR’s “The Larry Meiller Show” for a segment airing Memorial Day, a day to honor the memories of soldiers who died — soldiers whose names and stories are known, and those that are not.

‘That’s all we have’

After Armbruster’s father and father-in-law died, he said Moran became a surrogate grandfather to Armbruster’s kids. They watched Green Bay Packers games together. They talked fishing and hunting.

“My boys loved him,” he said.

But they never dared to talk about the war. Armbruster would silently look at Moran’s hands and think about the fighter pilots he went to war against. But he’d remember: “We don’t go there.”

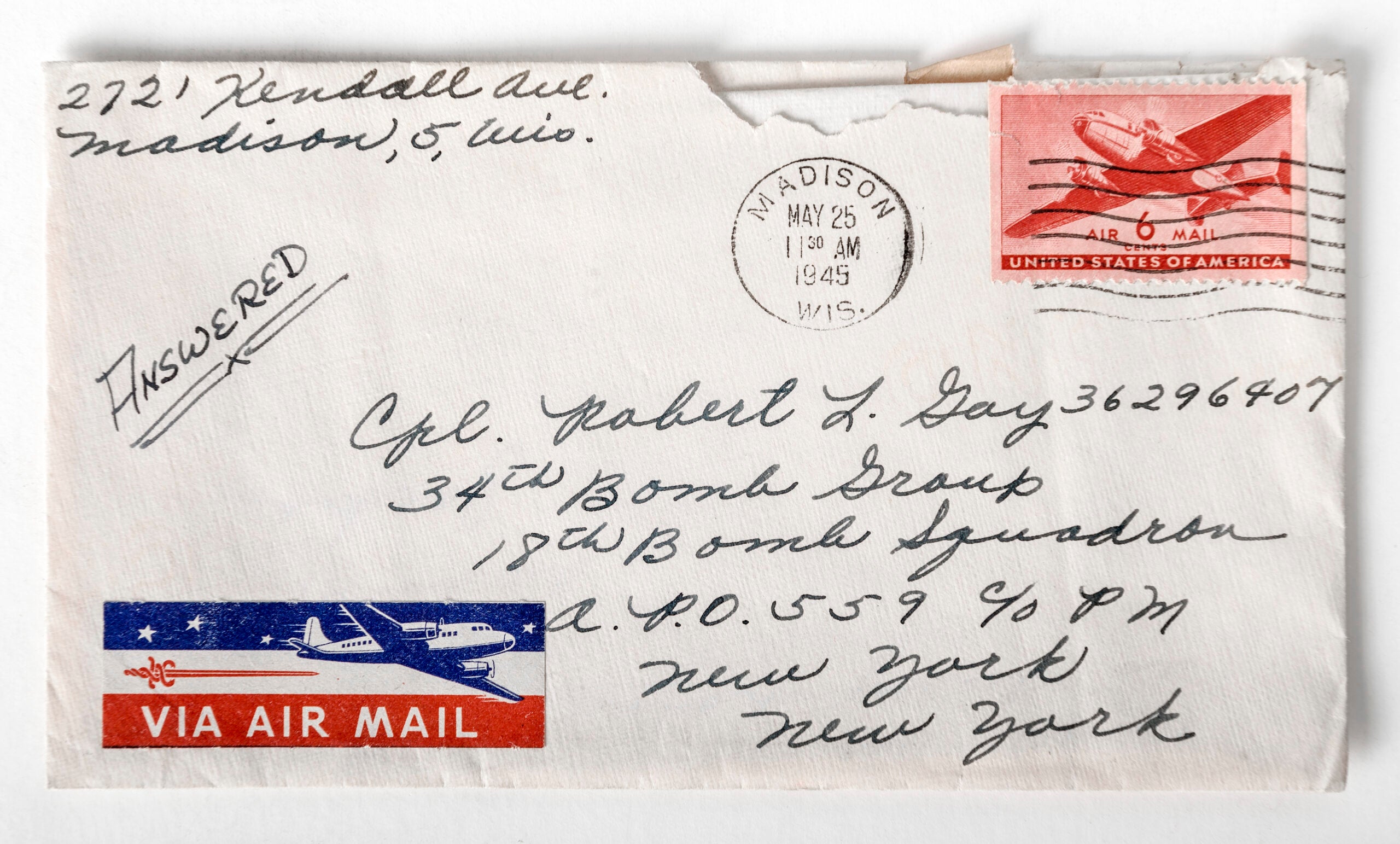

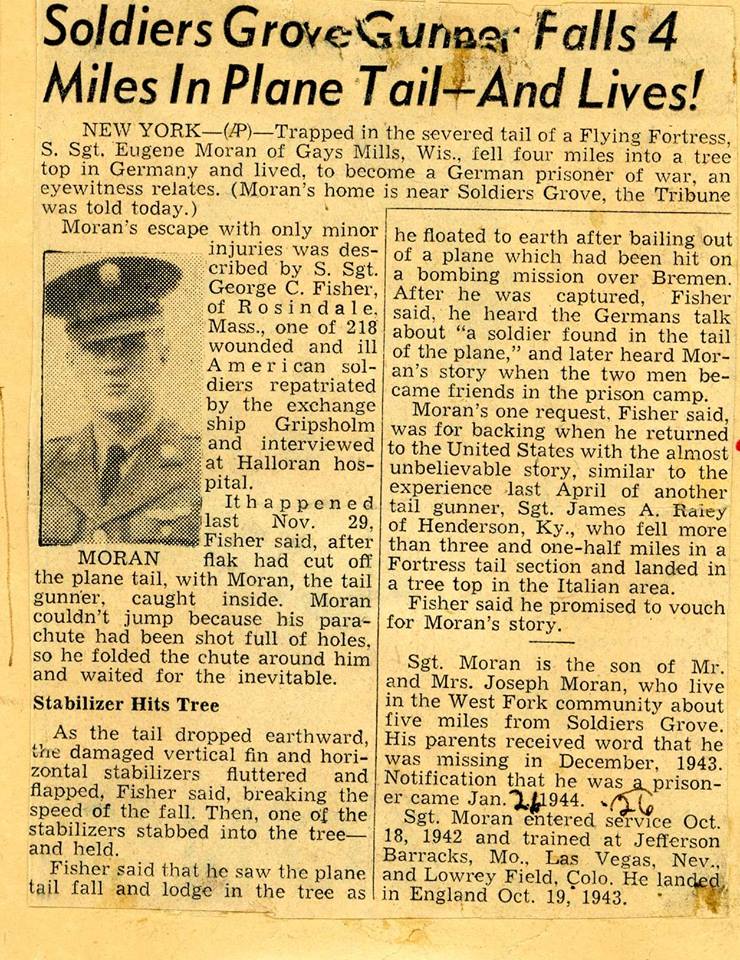

A few days after Moran’s daughter shared those words with Armbruster, she gave him a small La Crosse Tribune article from 1992 with the headline, “Soldiers Grove gunner falls 4 miles in plane tail — and lives!” The Tribune got some details through a S. Sgt. George C. Fisher.

“Moran’s one request, Fisher said, was for backing when he returned to the United States with the almost unbelievable story,” the newspaper article states. “Fisher said he promised to vouch for Moran’s story.”

When Moran’s daughter gave Armbruster the newspaper clip, she said, “That’s all we have.”

“Maybe someday I can have you talk with him, but whatever you find out, you’ll know more than we do,” he remembered her saying.

Moran started to share bits and pieces in 2007 as part of a Congressional veterans oral history project. U.S. Rep. Ron Kind interviewed Moran for about 20 minutes. He was finally going to talk. He didn’t end up sharing much, though. Armbruster said Moran gave short, cryptic answers and looked down a lot.

“But that got it going,” Armbruster said.

Moran was in his mid-80s. Armbruster and some of Moran’s friends through the American Legion knew how incredible his story was, but they didn’t want him to take it to his grave.

Finally, Moran decided he would share — but only if Armbruster wrote the book. So started the interviews, dubbed “Thursdays with Gene,” in January 2011.

The fall

Here is Gene Moran’s story, according to Armbruster, his book’s website and an obituary for Moran, who died in 2014.

Eugene Paul Moran was born in 1924 near Soldiers Grove on a small southwestern Wisconsin dairy farm.

One time, a young Moran was supposed to bring in the cows for milking, but he was late. This angered his father. Moran was late because he saw an airplane flying over the Kickapoo Valley and chased it.

“I got the pilot to wave back at me,” Armbruster remembers Moran saying. “Someday, I’m going to be up there.”

He became sick of dairy farm life. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, he desperately wanted to join the service when he turned 18. He went to the Army Air Corps recruiting base in Madison and soon discovered he still needed his parent’s permission. He tried forging the signatures, but he got caught.

So, he went home and lied to his parents, saying he already took the oath but just needed the signatures. He convinced his parents and he was on his way to gunnery school in Las Vegas, where he excelled.

“Some of the recruits had trouble handling those heavy .50-caliber machine guns,” Armbruster said. “All those years of milking cows by hand really had steeled his forearms.”

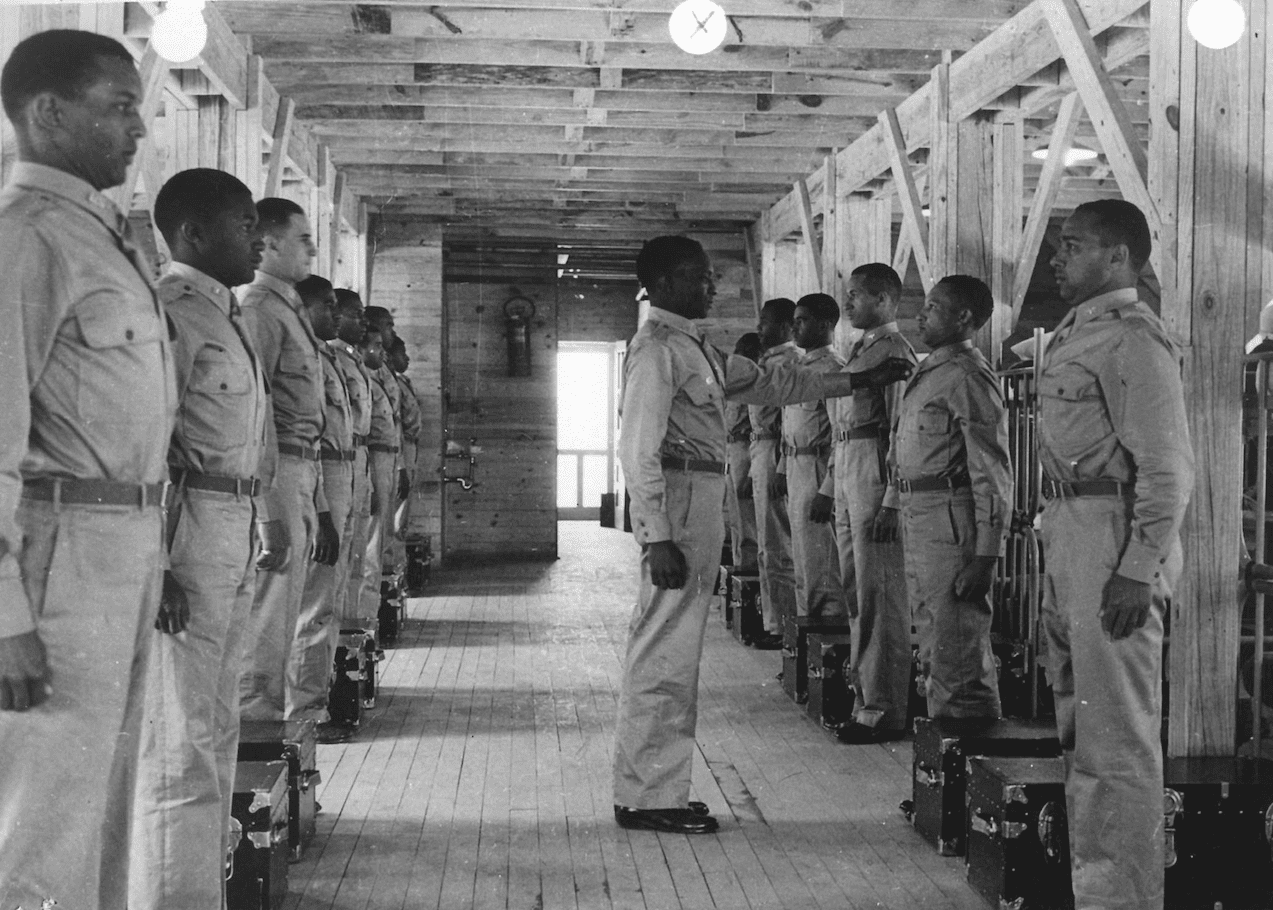

The crew on the Flying Fortress were tight-knit — as Moran put it: “Closer than brothers.” But Armbruster said these troops were “expendable” in the war. Many died.

Then came Nov. 29, 1943. Moran was on a bombing mission that targeted Bremen, a heavily defended industrial German city about the size of Milwaukee. Upon hearing that Bremen was their target, it left a lump in their throats.

Through constant shooting, the plane managed to drop its bomb load. But on their way back, the Flying Fortress was attacked by more German fighters. Moran’s crew was on their own. They fired everything they had. The sound was deafening.

One by one, his crewmates started dying. Moran was shot in both of his steeled forearms. An explosion left his ribs broken. A bullet went through his parachute. The damaged tail section of the plan started crashing through the sky. Moran recalled pulling out a rosary his grandmother had given him, rubbing the beads so hard it felt like he was rubbing flesh off his fingers.

“I was conscious all the way down,” Armbruster said Moran told him. “I just relaxed. I’m going to die. Why fight it?“

The tail section of the plane fell so fast, Moran’s teeth fillings popped out. He crashed into a forest. Armbruster visited the location on the 75th anniversary of the attack in 2018 when a German TV crew interviewed him.

“They asked me, ‘Well, you interviewed him. You’re writing the book. Can you explain how he survived?’” Armbruster said. “No, I can’t. I have no idea.”

Moran had no idea, either.

‘Do we dare believe?’

Moran couldn’t see. But he could smell the cold November air. He started grabbing nearby leaves and twigs and he started giggling.

“Oh my God, I cheated death,” Moran said, according to Armbruster.

French prisoners of war were out scavenging wreckage when they saw Moran. The prisoners returned with German soldiers. Ironically, Moran was lucky soldiers brought him back to the camp because if locals had found him instead, Armbruster said they would have just killed him.

Two doctors in the POW camp treated Moran’s extensive injuries and saved his life. Moran was treated like a celebrity as the story of his 4-mile fall spread.

But after he healed, Moran had to persevere through about 17 months in various POW camps, not knowing if the Germans would kill him and his fellow prisoners or keep them. And traveling between the different camps was dangerous. Moran thought he would die a few times as they endured heavy bombing.

“When people read this book, they’re going to be like, ‘My God, this guy had more lives than a cat,’” Armbruster said.

As all this was happening, Moran’s mother was back home, devastated. The family received a missing-in-action telegram just before Christmas. Moran’s older brother got married soon after the holiday, but the wedding felt more like a funeral.

They didn’t know if Moran was alive. But the family started getting anonymous letters from radio operators who picked up broadcasts that said an American fell 4 miles and lived. Someone had picked up his name and thought he was from Gays Mills, which was where the nearby post office was.

“So, they get about four or five of these (letters),” Armbruster said. “And it’s like, ‘Do we dare believe? Is this correct? Do we know?’“

Finally, the family got a postcard from Moran himself. The man who survived time and again when those around him did not.

Even his final stretch to safety was perilous. Moran and others had to cross a bombed-out bridge to reach an American camp. If he fell in the river, still swollen with spring melt, he wouldn’t be strong enough to swim.

With about 50 yards left, he collapsed. Would that be it? Would the man who survived a 4-mile crash, POW camps and bombings fall just short of safety?

Of course not. The Moran family wrestled and lived with the unknowns for many months and years. Months without word from Europe. Years full of, “We don’t go there.”

But there was only one way his story would end.

An American solider came down, picked him up, threw Moran over his shoulder like a feed bag and brought him to the camp.

“They made it,” Armbruster said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.